In every era of hockey, coaches have searched for the same edge.

At times, it has been:

- Better systems

- More structure

- New technology

- More information

Today’s game is no different. We have access to more knowledge than ever before—and with it, the temptation to use all of it.

But at the youth level, and even at the highest levels of the game, coaching excellence is rarely defined by how much a coach knows.

It is defined by what they choose not to use.

The Cost of Too Much

Most coaches do not fail because they lack ideas.

They fail because:

- They introduce too many concepts at once

- They correct everything they see

- They mistake activity for learning

- They confuse complexity with sophistication

Players are asked to:

- Process multiple cues

- Remember layered systems

- Adjust constantly

- Perform under emotional pressure

When cognitive load exceeds capacity, learning stalls. This is not a failure of effort.

It is a failure of judgment.

Clarity Is Not Simplistic

Clarity is often misunderstood as “dumbing things down.” In reality, clarity is a strategic choice.

It requires a coach to ask:

- What matters most today?

- What can wait?

- What will transfer?

- What can I let go of without losing the point?

Great coaches are not simplistic. They are selective.

They understand that development is cumulative, not immediate.

Restraint as a Coaching Skill

Restraint is rarely celebrated in coaching.

There is little external reward for:

- Letting a rep play out

- Ignoring a small mistake

- Saying nothing when you could say something

But restraint is one of the most advanced coaching skills.

It requires:

- Trust in the environment

- Confidence in the process

- Comfort with temporary disorder

Restraint is not passivity. It is deliberate patience.

Judgment: The Invisible Differentiator

Judgment is what allows a coach to decide:

- When to stop play

- When to let frustration build

- When to intervene

- When to step back

Two coaches can run the same drill with the same players and produce entirely different outcomes. The difference is rarely the drill. It is the decisions made in the margins.

Judgment cannot be copied. It must be developed.

Concrete On-Ice Examples

Example 1: Choosing One Teaching Point

A practice includes:

- Breakouts

- Neutral-zone play

- Offensive entries

A coach sees issues everywhere.

Instead of correcting all of them, they choose one: “Today, support underneath matters more than anything else.”

Mistakes are allowed elsewhere. In my experience as both a teacher and a coach, this is often where learning accelerates

Example 2: Letting the Struggle Happen

A drill breaks down where players are visibly frustrated and a large group of parents are watching. Worse yet, many parents subscribe to LiveBarn, and the coach knows the practice will be watched again later.

The coach waits.

After the rep: “What made that hard?”

The answer is already there. The coach didn’t need to provide it.

Example 3: Ending a Drill Early

A drill is running well—but energy is fading. The coach ends it early.

Why? Because learning was happening, and now it’s slowing.

Stopping at the right moment preserves confidence and focus. That is judgment.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In a world where:

- Content is endless

- Models are copied quickly

- Drills are shared instantly

Judgment becomes the differentiator. Players don’t need more ideas. They need coaches who can curate them.

From Youth to High Performance

At elite levels, coaches are praised for:

- Clear messaging

- Calm presence

- Efficient practices

- Precise intervention

Those qualities do not appear suddenly. They are built over years of:

- Choosing clarity over completeness

- Restraint over reactivity

- Judgment over ego

Youth hockey is where those habits are formed—on both sides of the bench.

Closing the Series

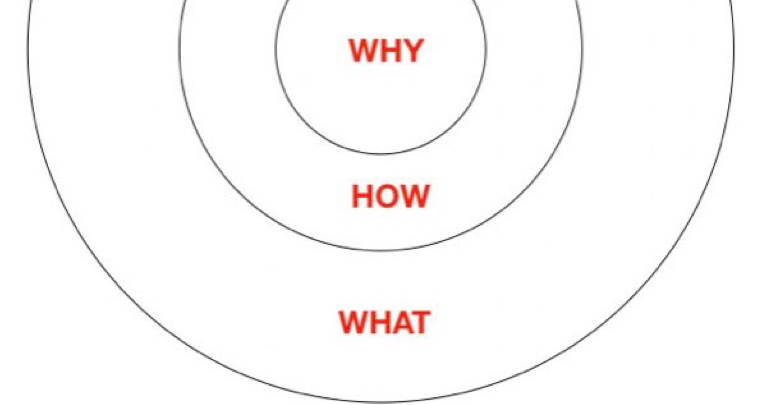

This series has argued four simple but demanding ideas:

- Meaning must come before method

- Environments shape behavior—and coaches shape environments

- Teaching still matters when timed well

- Clarity, restraint, and judgment separate great coaches from busy ones

None of these ideas are revolutionary on their own. And I for certain have not developed them. They come from my many mistakes as both a teacher, and a hockey coach. Together, they form a philosophy.

One that respects:

- Players as learners

- Coaches as educators

- Development as a long game

Hockey does not need louder benches or smarter drills alone. It needs coaches who know:

- What matters

- When to act

- And when to let learning unfold

That is not less coaching. It is coaching with purpose.