Introduction

As a player, it took me a long time, and in fact not until I started to coach did I learn to appreciate the old coaching expression: “Good defense leads to good offense.”

It would be great if you could simply score your way to a championship, but this rarely happens in hockey. You need to be able to score, but also, at times, you need to be able to defend and win a low-scoring game. If you defend well, you have the puck more, so you can attack more. Combined with good execution, decisions, and effort, you generally control both possession and territorial play. Occasionally, you can outscore a team with poor defense, but this is not a productive, long-term strategy. When you look back at the great success the Edmonton Oilers had under Glen Sather, you will see that yes, they could really score, but as the playoffs started and progressed, their dedication and effort to defend, as well as score, really improved. When your team achieves the label “hard to play against,” it’s usually because they play a complete game in both directions. Coaches don’t separate offense from defense, as it is a fluid game and both phases must be constantly connected: “You defend so you can attack.”

Before looking at some of the key concepts of defending, one must acknowledge that the most impactful defender is your goalkeeper. In my time with Canada’s National/Olympic Team, playing against powerful international opponents, this became very clear. Both Andy Moog and Ed Belfour spent a season with us and were terrific, often difference-makers. As well, Sean Burke invested a couple of seasons with the National/Olympic team, and not only was he an amazing goalie, but his attitude and effort could inspire our team. In all the games he played and all the shots he faced, I can honestly state that he never had a bad game! I don’t think I ever pulled him out of a game; he represented the center of gravity for our team. You could count on him every game!

Four Simple Concepts in Defending

There are many principles and concepts that contribute to becoming a good, consistent, and persistent defensive team. I want to simply focus on four concepts that, beyond solid goaltending, are very important when defending.

1. Collective and Connected Effort

-

Never underestimate the importance of effort or heart, but this is even better if the individual tactics and techniques are also good in 1 vs 1 situations.

-

At times, as an individual, you have to take “calculated risks,” but as much as possible, avoid “all-or-none” decisions, as sometimes you get nothing.

-

Defending is a mindset of determination and sacrifice combined with game sense. Effort plays are an investment in winning.

-

You collaborate with your teammates to collectively defend.

-

Defending is all connected through verbal and non-verbal communication, which keeps teammates alert and decisive. Along with anticipation, this often keeps you one play ahead. Accomplishing this takes you from reactive to proactive defending.

-

“The pass” is one of the attacking team’s most important weapons, but with anticipation, as or just before the pass is made, distances essentially become shorter as you are in movement. They may complete the pass, but the receiver is under so much pressure that a change of possession might occur.

-

Off-the-puck awareness with your “head on a swivel” is the key to taking passing options away from the puck carrier and causing a bad decision, which may lead them into trouble.

2. Numbers

-

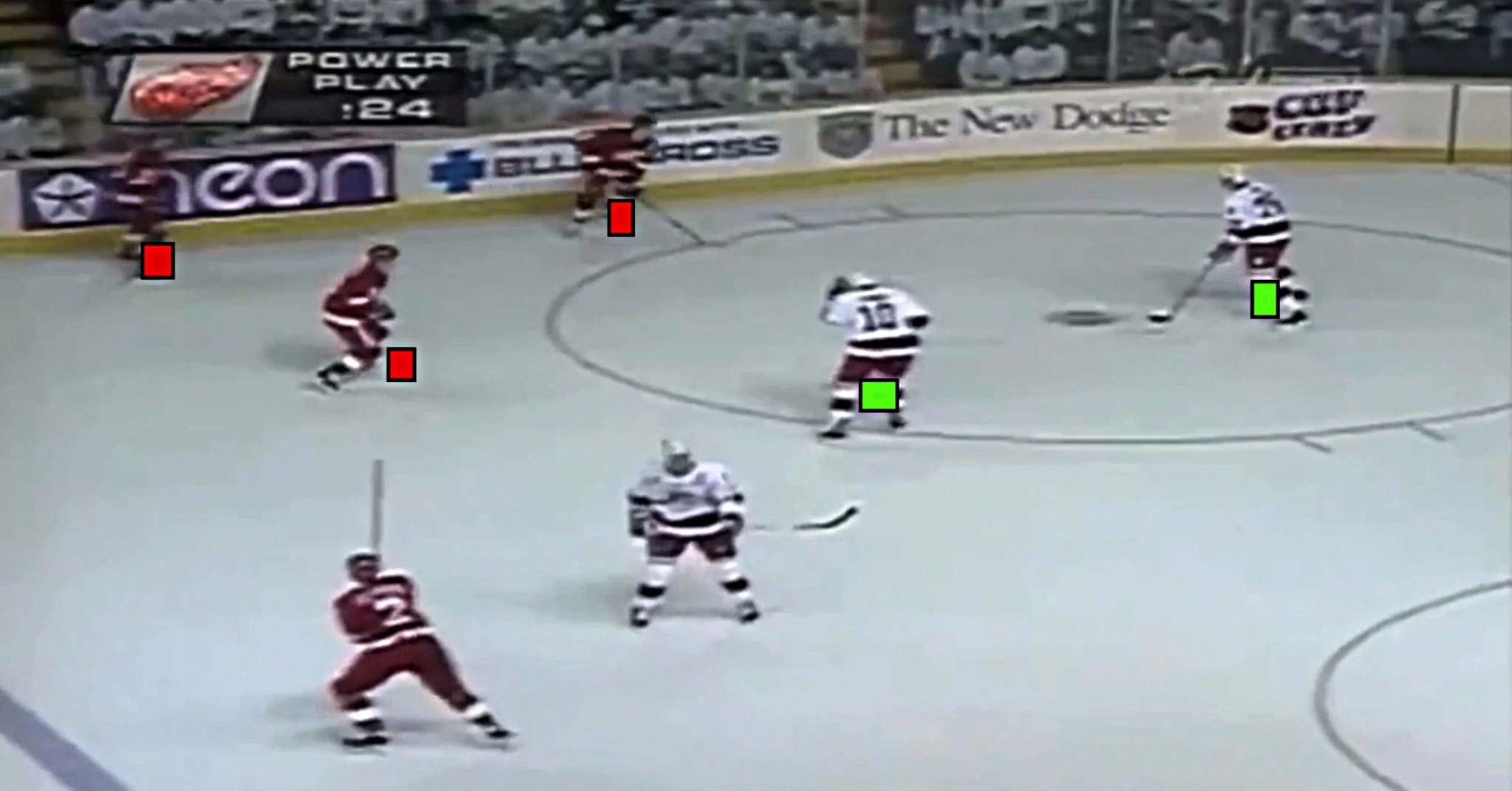

With even or superior numbers, you can aggressively pressure and be proactive.

-

When outnumbered, you are a little more reactive and sometimes you have to “shut down” and “stall” their attack. You defend space, not so much the opponent, and try with good stick positioning to momentarily control two opponents from one position.

-

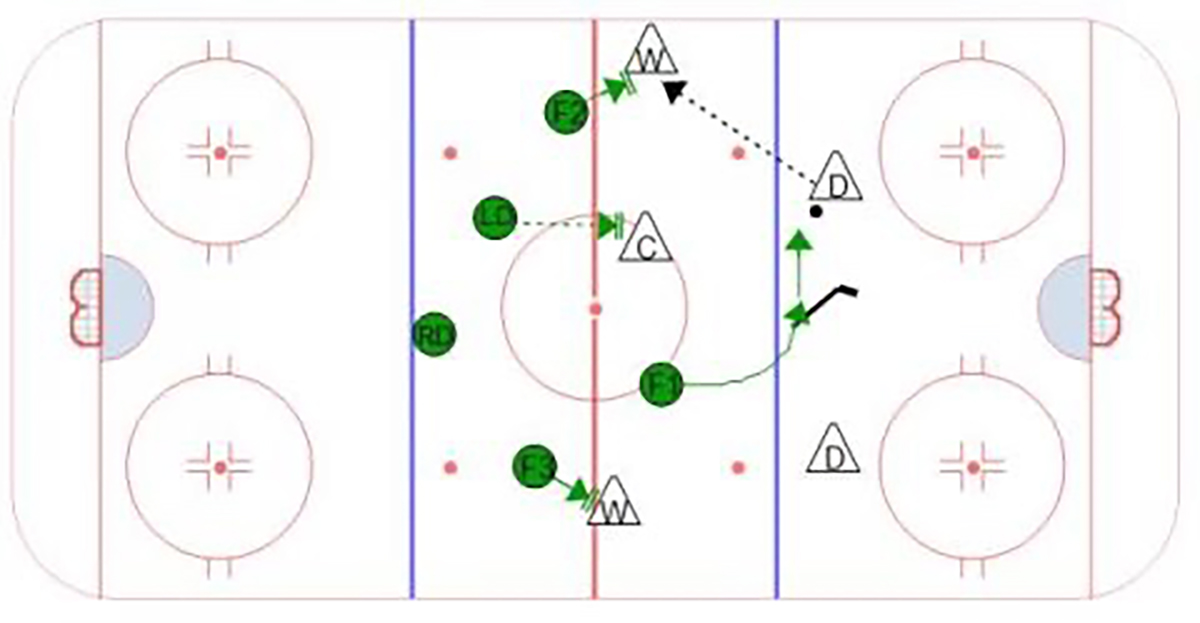

Often, how fast you can get organized D-side of the puck makes the difference. Hopefully, your defensive transition is quicker than their offensive transition. Numbers D-side is good, but organized and aware numbers D-side are better.

-

Defending is about manipulating and reducing space. However, on some occasions, errors or misjudgments occur, but one can manage these mistakes with balance in positioning.

3. Gaps/Separation

-

Space is adjustable, and at the correct moment, you have to restrict or reduce it. Often, you start cautiously or patiently by angling or steering, then suddenly aggressive pressure is applied. Numbers back and balance in positioning allow defenders to play tighter gaps/separation on attackers. The tighter the gaps/separation, the sooner you can confront or contest the puck. Tight gap checking reduces acceleration and escapability, so when you reduce space, it generally reduces pace. Close coverage on the puck carrier with an active stick often forces the puck carrier’s eyes down, making a penetrating pass between defenders difficult to find. The puck carrier’s next play often becomes simple or predictable.

-

Often, with tight gaps/separation, the puck carrier’s only choice is to give up the puck in a safe area. Not exactly as you had hoped, but it’s another possession for you with possibilities.

-

Smart puck carriers will try to create space through individual changes of direction or pace, forcing the checker to match and reset the gap or separation.

4. Layers of Support Behind Pressure

-

Be aware: fatigue tends to spread out defenders, and late in a shift, this can compromise defensive balance or spacing. Sometimes you have to concede space to consolidate positioning in key areas.

-

Depth or layers in support allow players close to the puck carrier to challenge and play tight, knowing they have cover.

-

When a team is defending alertly and everyone is engaged, you often get interchange or replacement between teammates from one layer to another to keep the pressure on.

-

Communication prevents hesitation, duplication, and frustration; all are toxic to good defending.

Individual Tactics That Allow Team Tactics to Work

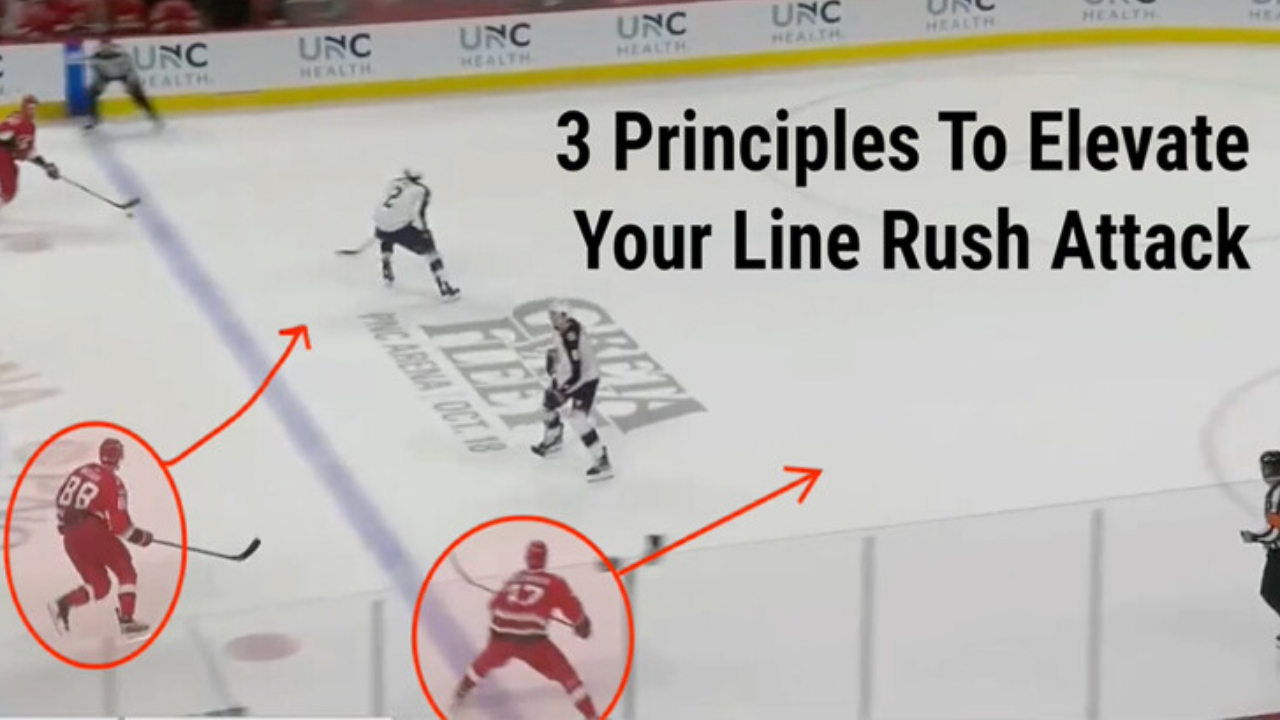

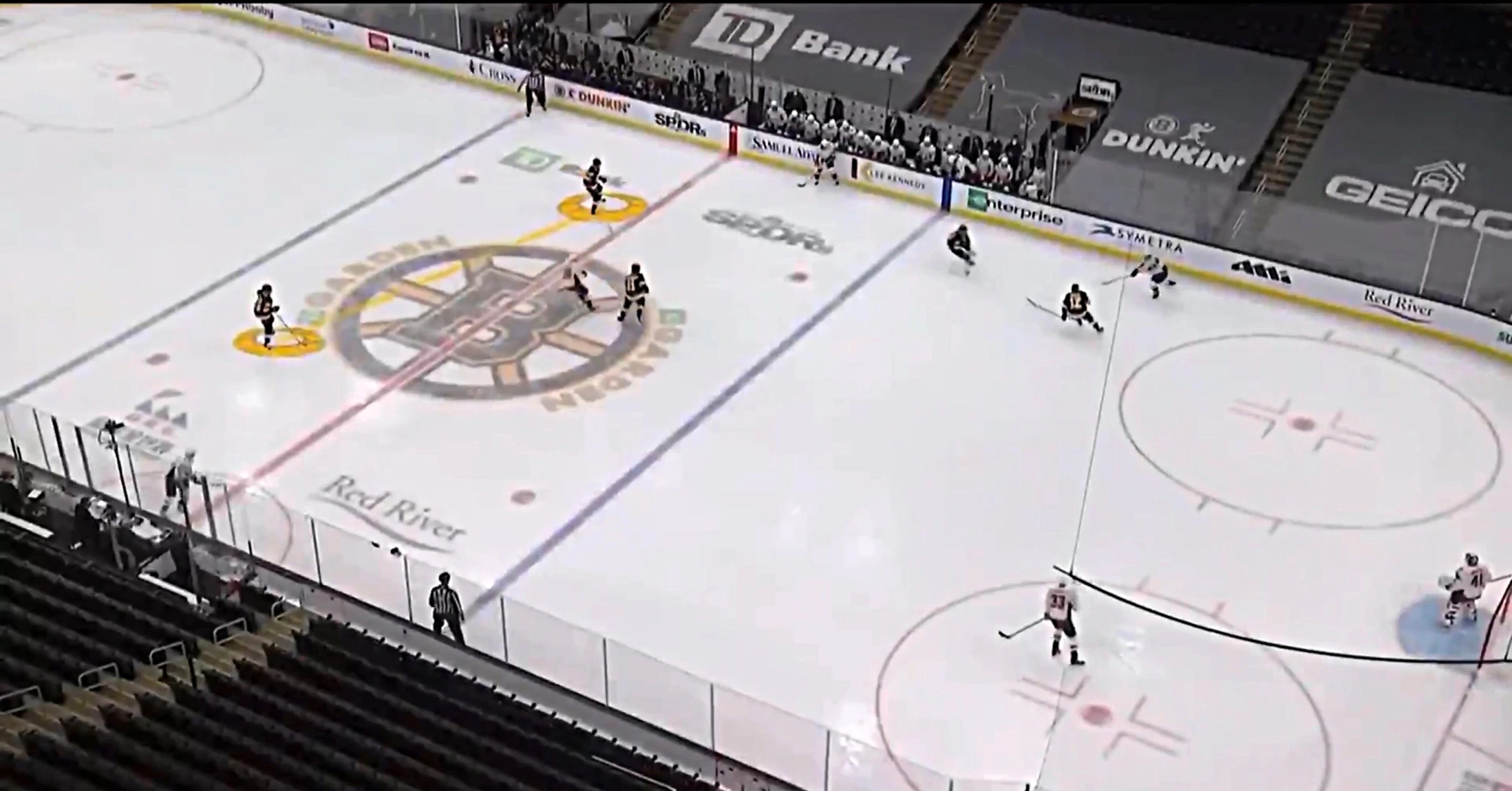

The game can be continuous, almost non-stop transition at times. To control space offensively or defensively, the five players on the ice have to all really work. For example, offensively, when you go from a breakout into the neutral zone and are heading to the offensive zone, possibly for an entry or a chip-in that could lead to a forechecking situation, you need your D-men to follow up the play. They have to push or close up the space between layers from the back to the front. This allows your D-men to get involved in the rush as a third or fourth man up. However, if your attack is forced to shoot it in, then your D-men are up close and create an active third layer to the forecheck.

Let’s look at the opposite scenario: your team’s OZP or forecheck is about to lose possession or pressure to the opposition. Now, you want your D-men to anticipate and quickly get D-side, and the forwards to quickly transition O to D, pushing from front to back to tighten the separation between layers. This hard, aggressive back-pressure by the forwards “squeezes” the opposition rush as they face tight gaps in front and behind.

Remember, in attack, you attempt as much as possible to play fast, play direct (e.g., get into high-percentage areas), and play deceptively (e.g., change point of attack). When defending, you try to slow the attack, deflect or channel it into lower-percentage areas, and try to make the attack predictable. The attacking team tries to control space and make the ice bigger, spreading defenders. The defending team tries to reduce space to keep the ice smaller and maintain manageable spacing between defenders.

Another common defending situation: you are always trying to exert some degree of pressure, active/aggressive or contain/delay. In every defending situation, you need support or cover behind the pressure to create another layer of security. Obviously, pressure or support roles require two players. The other three provide balance in positioning. With awareness, they take away passing options/lanes and escapable space.

The closest defender, based on separation from the puck carrier and opposition numbers close to the puck, must decide on aggressive or contain pressure. If possible, get close and stay close to get stick on puck to force the puck carrier’s eyes down. If it’s not an aggressive pressure situation, then angle or steer to slow their attack and make it more predictable.

The next closest defender must assess the supporting distance needed. He has to quickly gauge how much progress the closest defender is making on the puck carrier. Always have your head on a swivel to see where the puck carrier’s support is coming from. If the closest man is making progress, reducing the puck carrier’s speed and space, then the support man can close up and be prepared for a possible loose puck or scrum. If the closest man is not going to get the puck stopped, the support player maintains more distance.

The other players further from the puck must keep their heads on a swivel to find attackers off the puck and keep sticks in priority passing lanes.

If the closest man or support man stops the puck, then the others must shrink/compress space so attackers have less room and more congestion. Wherever this action is taking place on the ice, recognize if attackers are “breaking” the pressure; as early as possible, start transitioning to get D-side position on the puck and their attackers.

There will be times when you can’t stop the puck; rather, the opposition makes a pass, which may require teammates to take over pressure or support roles. This requires quick, fluid exchanges between teammates, made easier through communication.

Summary

The old expression “good defense leads to good offense” is true. Never forget: the concepts provide an overview, but individual defensive techniques and tactics, along with game sense, make collective play work. Your ability to be consistently good 1 vs 1 is a cornerstone of defending. More games are lost because of simple 1 vs 1 mistakes than by electrifying offensive plays.