I’ve always believed that if we want our players to eventually reach higher levels, we can’t coach them like they’re lower-level athletes. That doesn’t mean running systems they aren’t ready for or overwhelming them with information — it means giving them an environment that challenges them, stretches them, and exposes the things we need to teach.

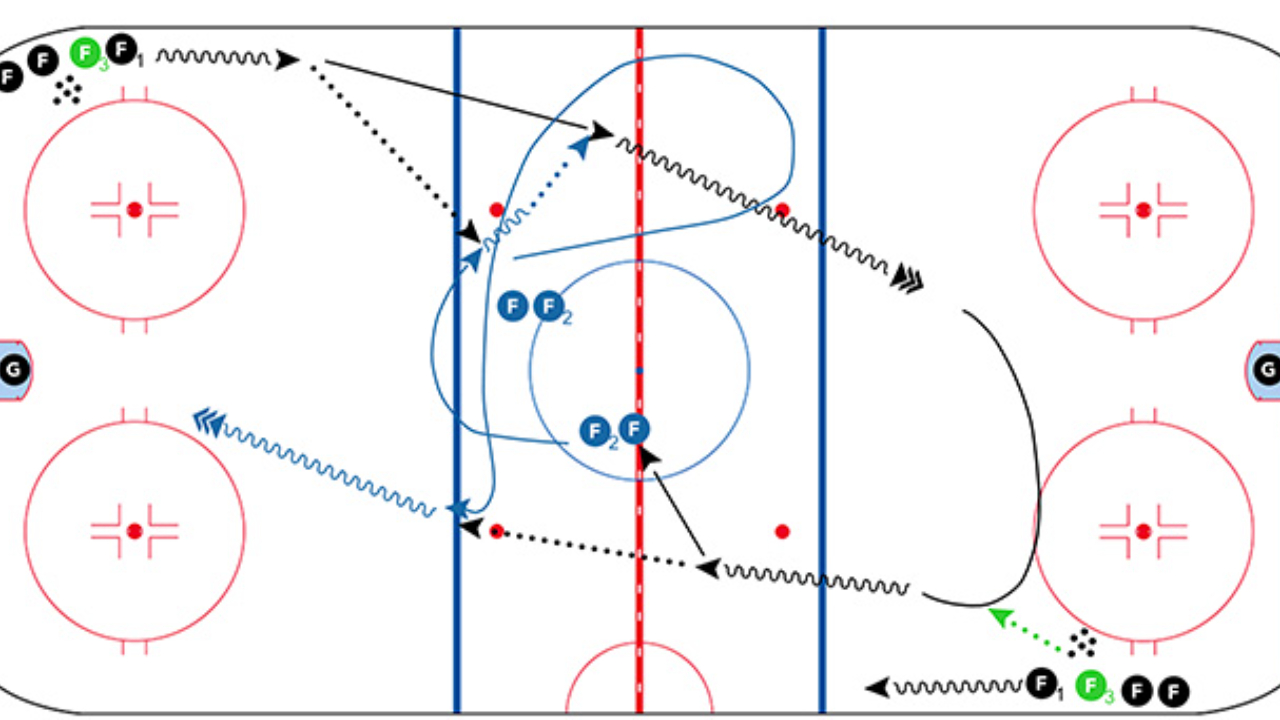

A few weeks ago, I watched a AAA U10 team run a drill often referred to as the “Team Canada drill.” It’s a flow drill built on timing, shoulder checks, curling low, catching passes in motion, and executing under pace. On paper, it's far too difficult for most U10 teams.

But I decided to run it anyway.

Not because I expect my A team to look like Team Canada.

But because I want them to grow toward that environment if that’s the level they dream of playing at. And because we needed something that would expose our biggest weaknesses — breakouts, neutral-zone passing, timing, and the ability to play in flow.

This drill does exactly that.

The first night was exactly what you’d expect. Kids were confused. The flow broke constantly because the shooter forgot to pick up a puck. Coaches had to stand at every curl point just to hand players the next pass. One side of the ice ran faster than the other. Some players got frustrated. My assistants got frustrated. And if a single pass was off, the entire sequence died.

But I never felt like scrapping it.

I went in knowing this was going to take weeks. Maybe months. And that’s the point. If a drill only works perfectly on day one, it’s not exposing anything that needs to be fixed.

What this drill exposed about our team was exactly what I hoped it would:

• No shoulder checks

• Poor timing — players curling too high or too shallow

• Passes thrown to space instead of tape

• Kids waiting for passes instead of skating into them

• Leaving early and ruining the next touch

• Not looking up before making decisions

The smallest mistake — a kid leaving early, a pass mistimed by half a second, a weak curl — made the entire flow crumble. And that’s why this drill matters.

Because it forces the details to appear in full daylight.

By the second day, timing actually improved. Players started catching passes in motion. Coaches were more aware of when to send the next skater. The drill still wasn’t clean — but the improvement was clear. Breakouts? Too early to tell. Confidence? Also early. But the foundation was starting to show.

I want coaches reading this to understand something:

We can’t lower our standards just because athletes are young.

Too many of us are scared to try hard drills because we’re worried about how it will look. Worried parents won’t understand it. Worried other coaches will judge. Worried the flow breaking means we failed.

But that’s ego.

That’s insecurity.

That’s coaching from fear instead of development.

If kids fail a drill, good.

That means we chose the right drill.

If they struggle, good.

That means we’re exposing the exact areas where they need reps.

If it looks messy, good.

That means we’re coaching instead of entertaining.

We ask kids to step outside their comfort zone every day. We expect them to handle mistakes and frustration and confusion. We want them to push through when something is hard.

But if we aren’t willing to be uncomfortable as coaches — to teach a drill we know might fall apart — then we’re asking players to do something we aren’t modeling ourselves.

This Team Canada drill forced our team to grow, and it forced me to grow with them. It reminded me that patience, not perfection, is the real skill in coaching.

And if we stay patient — with the drill, with the kids, and with ourselves — the progress will come.

Download the drill here: