In hockey, size is a well-known factor that influences recruitment, scouting and team selection. But how big of a role should it play?

There he was, lacing up. The player I drafted out of U16 a year or so back. He stood up to greet me and the full extent of his growth since I’d seen him last was immediately evident. At 6-foot-3, it was also clear that he had been in the gym over the last year. His lean, but well-muscled arm seemingly stretched out across the room reaching mine for a fist bump. Our Equipment Manager came by showing some distress. He was having trouble finding the largest sizes of equipment to outfit the young prospect. From the corner of the room, a fast but small sophomore forward murmured, “I think I can skate right through this guy’s legs.”

In hockey, size is a well-known factor that influences recruitment, scouting and team selection. This selection bias is known in sports that demand a physicality, or a certain physical make-up or characteristic to excel. The practice of selecting athletes by body type to fit into a sport is described in sport science literature and is apparent when watching sports like gymnastics, basketball or football. In gymnastics, small, powerful body types are typical. In basketball, the very tall athletes with incredibly long limbs dominate. In football, densely muscled athletes with high absolute strength are chosen by position with the most immense taking position along the line of scrimmage.

Three basic somatotypes describe and depict the human body and to a large extent the body’s functional capacity. The somatotypes are endomorphic, mesomorphic and ectomorphic. With endomorphs being shorter, with more mass, larger bone density and greater fat percentages. Mesomorphs enjoy muscular physiques, higher percentages of lean muscle mass and average to less than average body fat proportions. While ectomorphs are tall, lean with low relative body mass and fat percentages.

Body types that are taller with longer limb lengths, greater muscle mass and thickness, more elevated bone density and less body fat, demonstrate physical advantages in force production, movement potentials like acceleration, speed and possible more commanding abilities in muscular endurance over smaller bodies. Their abilities as athletes are not hidden. Their genetic abilities and capacities are tipped by parents, siblings and are familial. These abilities are however refined and stimulated through growth, development and as mentioned, the environment. These people become athletes and those that are further exposed to sound athletic development opportunities tend to reach the top of their chosen sport often as professionals.

Size variables like height and limb length, for example, are directly correlated to the body’s ability to generate forces like radial and linear velocity. In hockey, this means the big player has a shot and/or the large centreman can dominate when he goes hard to the net. Players with long limbs and enough muscle mass, strength and suppleness can deliver powerful and rapid movements. They can be physical winning puck races and battles low, but can also find loose pucks, get a handle and fire the puck quickly. Defensively, large players dominate space, taking away ice and time from smaller attackers. You can hear coaches talking about reach and sticks in lanes. Reach is a result of size. “You can’t coach size” goes the old adage…it remains true in the modern game; despite rule change and modern technological changes to equipment.

In the present day, at high performance and professional categories of play, we see defencemen and goaltenders as two positions where heights and weights exceed the average person. Big goaltenders are preferred because of their ability to take up net space, cover high scoring areas and limit scoring chances. Massive D-men dominate through body position, deflecting the rush, slowing the attack, taking away valuable real estate and punishing opponents.

But, when it comes to forwards, body sizes types tend to vary considerably in our game. Small, agile and quick forwards have a place in the game and can add dimension and depth to team personnel. Similarly, tall, lean forwards, usually through the middle (centreman) can create openings for others and can act as valued net-front positioning for a variety of tactics.

Having said all this I would hesitate to recommend player selection on the basis of somatotype alone in hockey but, I would suggest that it is an undervalued, and infrequently used methodology in scouting and in prospect selection. If you are considering its use, I would suggest quantifying and tracking anthropometric data with comparisons to normative values and growth and development charts. These values are easily found and are repeatedly referenced in the Long Term Athlete Development Model.

There is a large body of evidence and sports research on anthropometrics, growth and development and even a phenomenon known as the relative age effect. The RAE describes that those born in the first few months of a calendar year tend to be taller, tend to weigh more and tend to outperform others in their birth year athletically and even academically. Their birth order (January, February and March born) place them ahead in terms of their growth and development over their peers who are born later (October, November, December born). The more mature can be a half-year older than the others in their age and athletic cohort (school and sports). This means they stand out, are selected first and that they have a physical advantage that is supplemented through their exposure to better coaching, better environments, higher-level competition and even better training opportunities. Recent studies by Varvey-Parent, Desjardins and Harvey entitled Factors Affecting the Relative Age Effect in NHL Athletes describe a lower than previously reported RAE in the current NHL and even a lesser RAE in European countries. Nevertheless, the fact is that a selection bias based on size/maturity remains in amateur sport and the physical advantage of the more mature athlete persists.

Interestingly enough, the same body of research points out some pitfalls of selecting early maturers. For example, chronological selection can neglect and omit late developers, the lesser sized player who isn’t competing well in U14, but may mature later exceeding the early grower down the line. This same player will also spend more time in sustained development and put more time in training than their counterparts who get shuffled quickly into playing more and practicing less. Late developers, could in the long term, end up being as good or better athletes.

Coaches you are left with some important considerations when selecting players and your teams.

These can include:

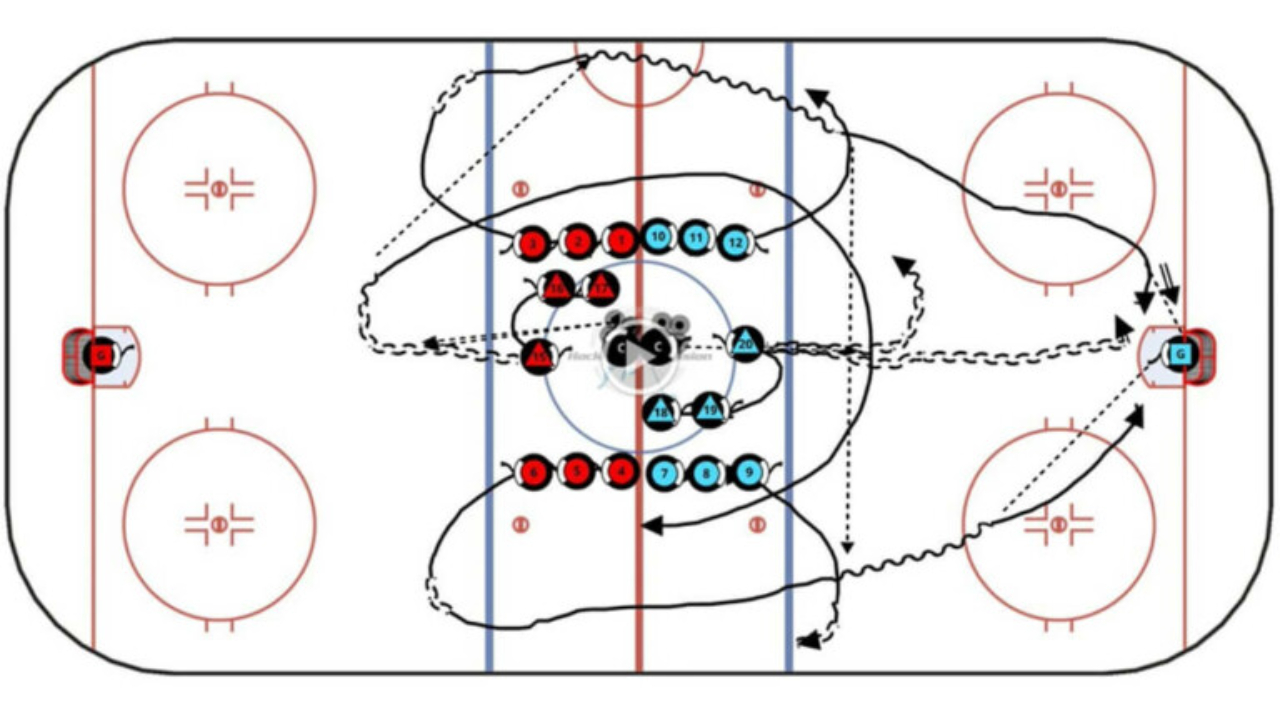

- Shaping your prospect list and scouting priorities by examining the age, stage and level of play at which your team is competing. For example, players that are in U22 category have gone through their peak height velocity (PHV) and are at or nearing the end of their muscular development window. This has implications for selections. Players in the U16 age group are in the maturation phases; expect and plan for varied sizes and capacities at this level. Don’t forget about the small(er) kid who may look a little scrawny, but loves the game. He just might be a late developer.

- Fill position vacancies with players who match your positional and team tactics/play philosophy. This will help you avoid frustration in the competitive phases of your season. It is akin to placing round pegs in round holes and square pegs in square holes. Expecting big players to be fast and agile or small players to be physically imposing can create critical errors on the ice technically and tactically.

- Consider position-specific somatotypes in high performance, and in older ages and stages of play. Scout and build rosters and depth by position by searching for and selecting players by comparing their defined physical attributes and characteristics with a set checklist. Record and capture anthropometrics, growth and physical capacities at evaluation camps, combines, sports testing facilities and programs. Seek expert advice to interpret these data sets.

- Seek out scouting information on growth and development markers and determine where the prospect is in terms of their personal/athletic growth and development. Are they an early maturer, a late developer at peak growth, or just starting? What is their genetic potential?

- Consider the strengths and weaknesses of players based on their somatotype and anthropometrics. Where can the team benefit from the big player or where will they be exposed? When can the small player surprise the opposition and when should they be resting on the bench? What situations will they excel best?

Body type is a predictor of success in ice hockey, but only when it is strategic and used well. In today’s game, all body types can play, develop and excel. Our role as coaches and sport developers is to provide the opportunity for success.