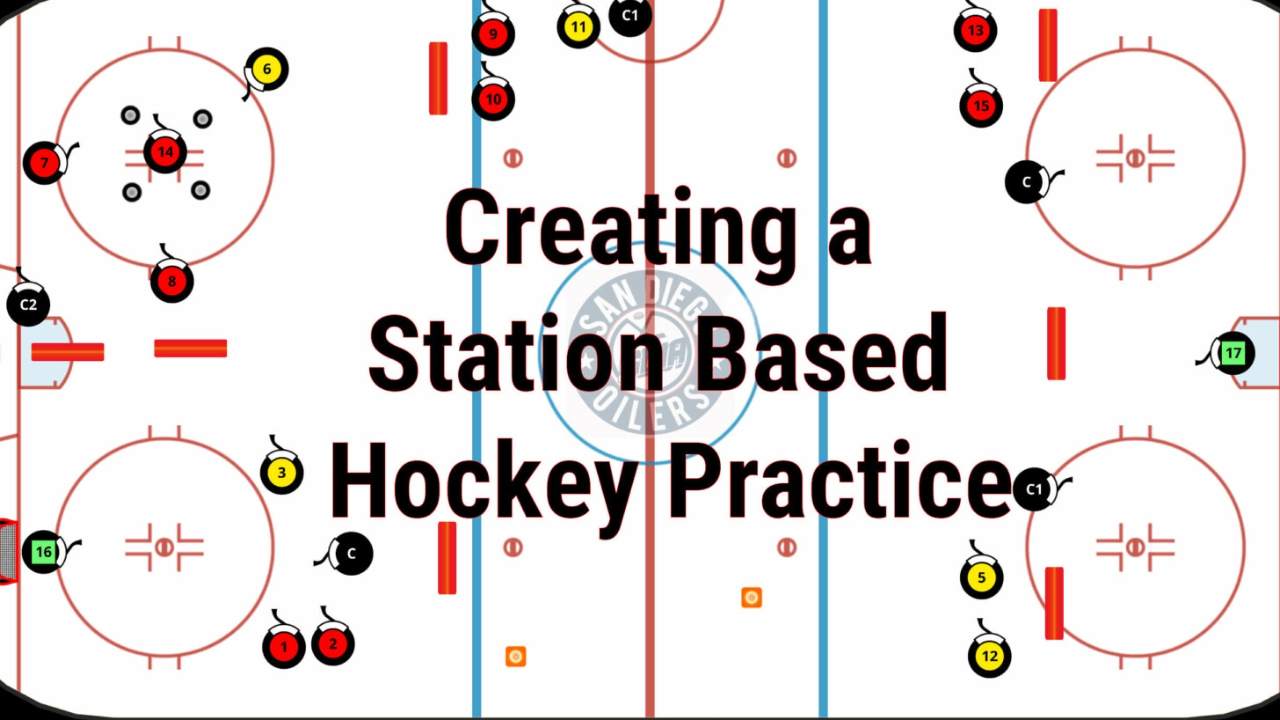

One of the greatest advantages of platforms like The Coaches Site is the opportunity to learn, share, and refine modern hockey insights. My own growth as a coach has been shaped by aligning three core pillars: the tactical vision I have for the teams I help coach, the methodology I prefer to teach, and the underlying science of how athletes learn. Coaching theories are vast and varied, but the most effective approach is the one that aligns with your personal philosophy, or better yet, creates a unified language across your entire team or organization.

I haven’t been a head coach for a team in some time due to other commitments. That, however, has never stopped me from thinking deeply about how I like to coach and the science behind player development. The head coaches I’ve worked with over the past years have generously allowed me to apply my philosophy, and I’m grateful for their trust.

By surrounding myself with expert hockey minds and leveraging high‑quality professional resources, I’ve focused on finding a path that truly optimizes player development. The concepts of Puck, Support, and Balance (PSB) and Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) referenced throughout this article are not my original inventions; they are the result of years of learning from mentors, peers, and elite coaching materials. My contribution has been stitching these elements together through the 3C’s of practice planning, creating a structured and practical framework for development from my perspective.

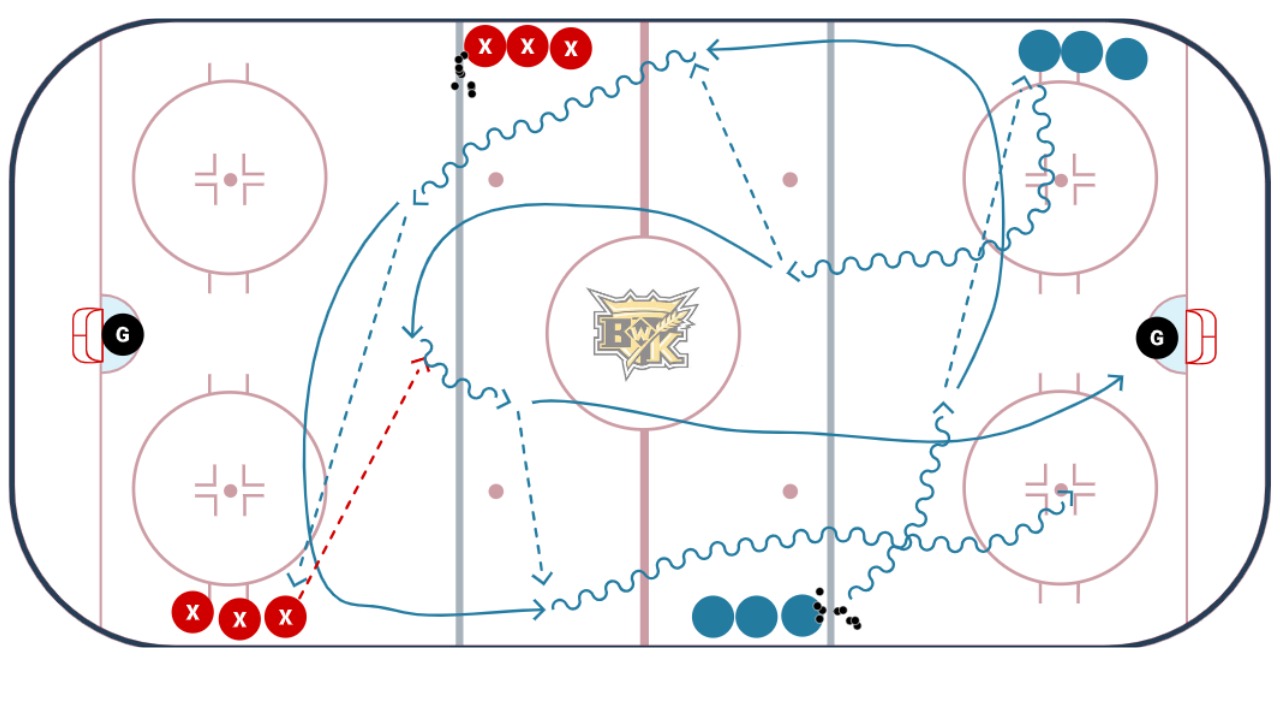

With that foundation established, the next step is understanding how these ideas actually shape what happens on the ice. The principles that follow repetition, structure, and intentional progressions form the backbone of a development model that accelerates learning and builds true game intelligence. Player development in youth hockey accelerates when practices emphasize consistency, repetition, and purposeful variation. While it can be tempting to introduce new drills every week, research and on‑ice experience showed me that modifying familiar drills is far more effective than constantly replacing them. A season should function like building a house: progress comes from laying bricks, not from switching blueprints. When players know the structure of a drill, coaches can spend valuable ice time developing skills rather than explaining diagrams.

1. The Science of Improvement: The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

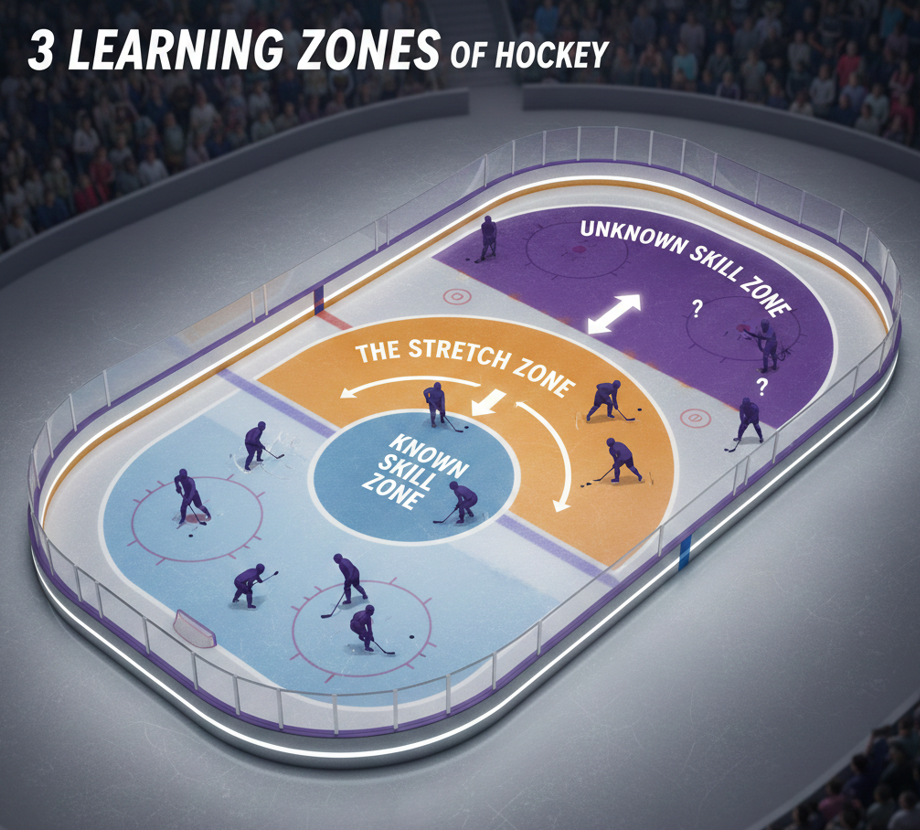

The concept of the Zone of Proximal Development originates from the work of developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who described learning as most effective when a learner is guided just beyond their current level of independent ability. In youth hockey, this principle applies directly to how players acquire skills, build confidence, and stay engaged.

Effective learning happens in the “Stretch Zone”, the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). This is the space between what a player can already do independently and what they cannot yet do, even with help. The goal of coaching is to operate in the middle, where players succeed with guidance or a small adjustment.

The Three Learning Zones

Just like in hockey, ZPD can be understood through three distinct zones, and that’s how I’ve correlated them in the image below.

Known Skill Zone

Players operate with full confidence and independence. Skills in this zone are already mastered and require little cognitive effort. Examples include basic stride mechanics, stationary passing, simple puck control, or predictable 1‑on‑0 attacks for younger players. While this zone feels safe, staying here too long leads to stagnation and disengagement.

ZPD — The Stretch Zone

The ideal learning environment. This zone bridges the gap between known and unknown skills. By modifying a familiar drill, tighter space, increased pressure, limited touches coaches guide players into a zone where they can succeed with support. This “controlled stretch” aligns directly with Vygotsky’s theory that learning thrives when challenges sit just beyond a player’s current mastery but remain achievable with guidance.

Skill levels vary across every roster, so each athlete’s stretch point is different. You may need to break players into skill groups, with each group working through its own progression to stay in the appropriate stretch zone if you feel it’s necessary.

Unknown Skill Zone

Players encounter skills that are too advanced or unfamiliar to perform successfully—even with help. Examples include executing a 2‑on‑1 read under pressure, applying PSB roles in chaotic game situations, shooting in stride with a defender closing, or making weak‑side support reads at high speed. Younger players in this zone often feel overwhelmed, and learning shuts down.

2. The 3C’s Framework: Structuring Effective Practices

A highly effective practice model follows an 80/20 structure: 80% familiar, configurable drills and 20% new content for specific needs. This approach is built on the three pillars of the 3C’s, Consistency, Controllability, and Configurability. Together, these elements support skill retention, cognitive clarity, and visible progress.

Skilled players can split their attention quickly and adjust on the fly: I have the puck, what are my options? I don’t have the puck. Should I attack or where should I support? The game changes rapidly, and players must constantly shift their focus, much like a chess match. Hockey rewards those who can recognize and act within short windows of opportunity to make a pass, take a shot, or create space. When the original plan closes, they must move on immediately and find the next best option. Speed in decision making needs to translate to positional urgency on the ice.

Practices should be structured to build not only speed and urgency in skating, but speed in decision‑making as well. Strong practice design rooted in Consistency, Controllability, and Configurability creates the environment players need to develop those habits.

Kids Learn Through Repetition

Youth athletes improve by repeating movements, not by encountering new drills every session. Familiar drills allow players to focus on execution rather than instructions. Repetition builds confidence, reinforces proper habits, and creates the foundation for long‑term skill development.

Better Thinking → Better Movement

When players already understand a drill, less explanation is needed, cognitive overload drops, and more quality reps happen in less time.

Progress Becomes Visible

Consistent drills make improvement easy to measure. Coaches can highlight growth by saying, “Last week this was a struggle, look how much better it is now.”

Why New Drills Still Matter

While repetition is powerful, too much sameness can lead to boredom, lack of challenge for advanced players, and players going through the motions. This is where new drills play an important role. Introducing a new drill can target a specific skill set your team needs to develop, or it can supplement a skill that isn’t catching on through your existing drill package. Sometimes a fresh structure, angle, or constraint helps players finally connect the dots. New drills keep practices engaging, provide variety when needed, and ensure that every athlete continues to grow within a balanced, intentional development model.

Consistency

Familiar drills create predictable progressions. When players know the structure, they feel safe enough to attempt difficult skills. This stability reduces cognitive load, improves skill retention, and makes visible progress easier to track over time.

Controllability

A drill must allow coaches to consistently reinforce a specific fundamental balance, support, angling, or another targeted skill. Multiple coaches can focus on different skills within the same drill, and controllability allows coaches to quickly identify when a player drifts into the Unknown Skill Zone.

Configurability

A strong drill has a familiar structure that can be adjusted instantly without lengthy explanations. The same drill can be made harder for advanced players and simpler for beginners. Instead of teaching a new drill to work on “Support,” coaches can add a constraint to a drill players already know.

3. The Importance of Foundational Skill Work

Even with a strong emphasis on repetition and configurability, foundational hockey skills must remain a non‑negotiable part of every practice. These core elements form the base upon which all advanced concepts including PSB, decision‑making, and game intelligence are built.

Essential Foundational Skills

-

Skating Stride & Edge Work

-

Puck Control

-

Passing & Receiving in Stride

-

Shooting in Stride

-

Physical Play & Contact Confidence

Foundational skills are not optional add‑ons. They must be present at every practice, regardless of age or level. Without them, higher‑level concepts cannot take root and re-enforcement is also necessary..

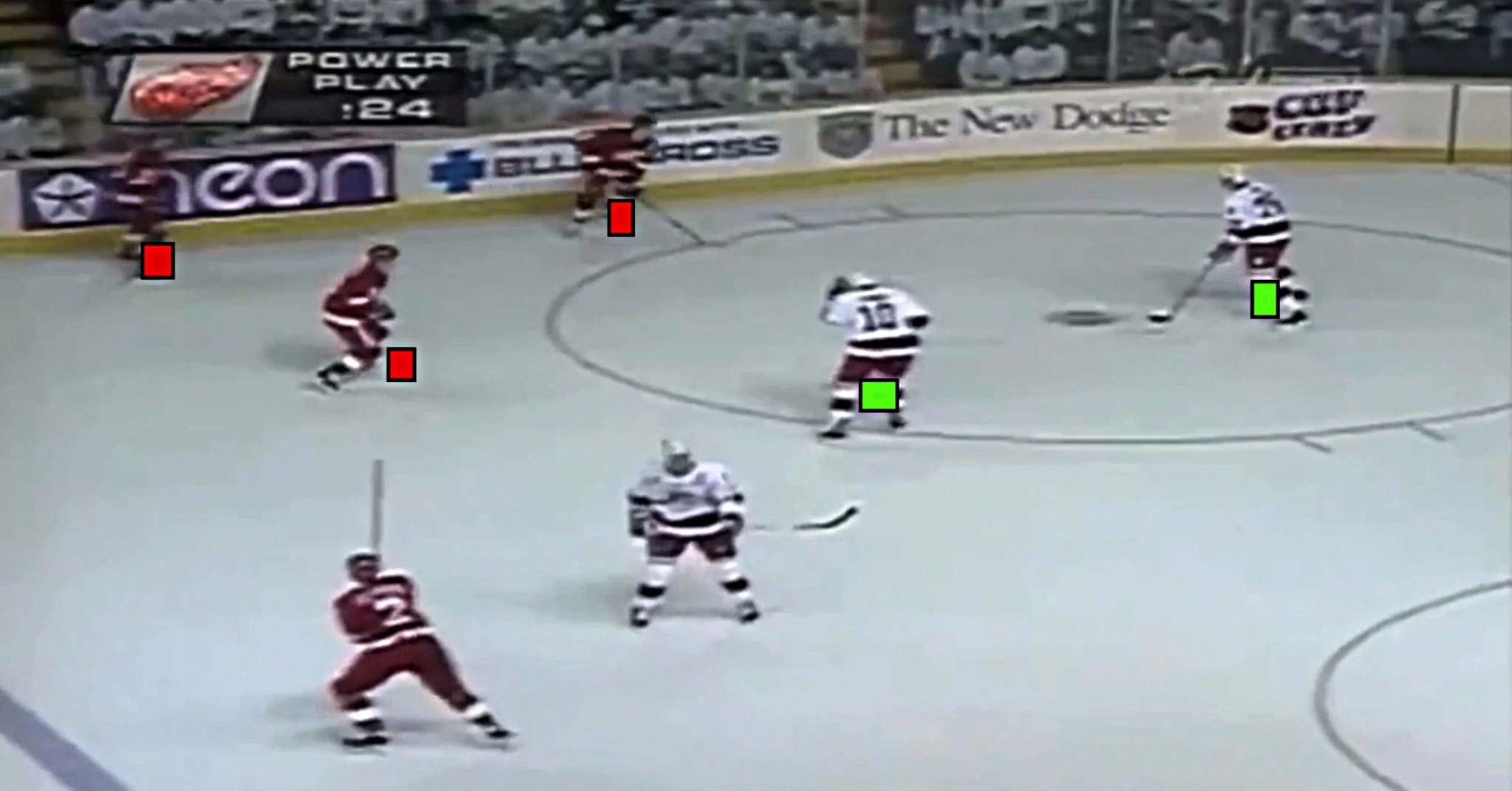

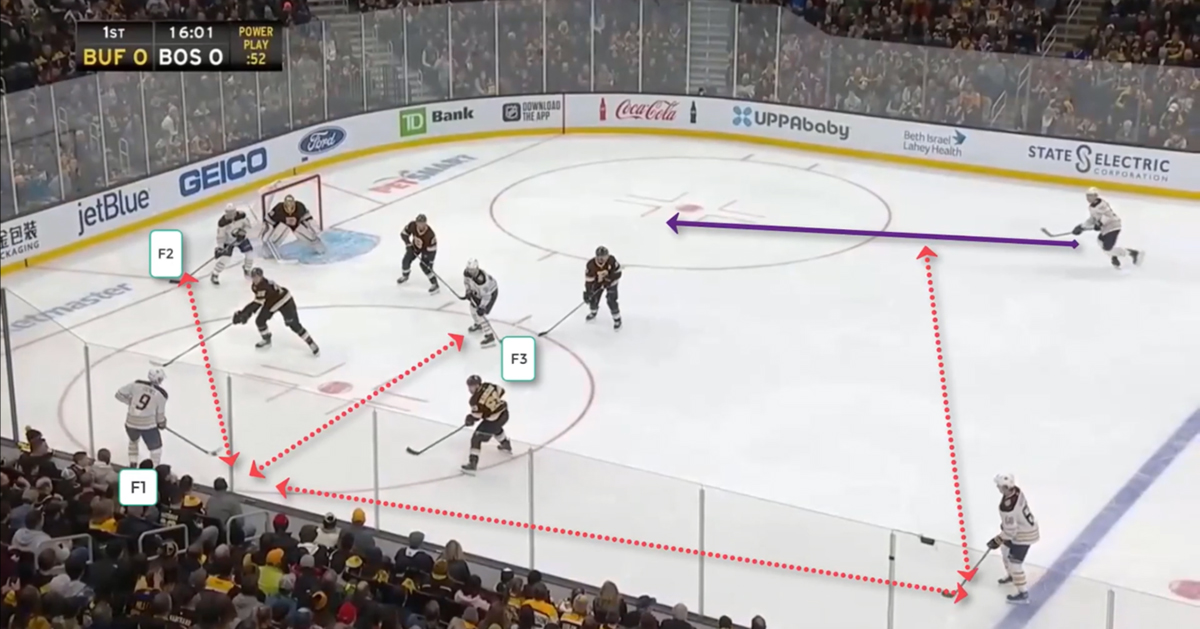

4. PSB: The Foundation of Game Intelligence

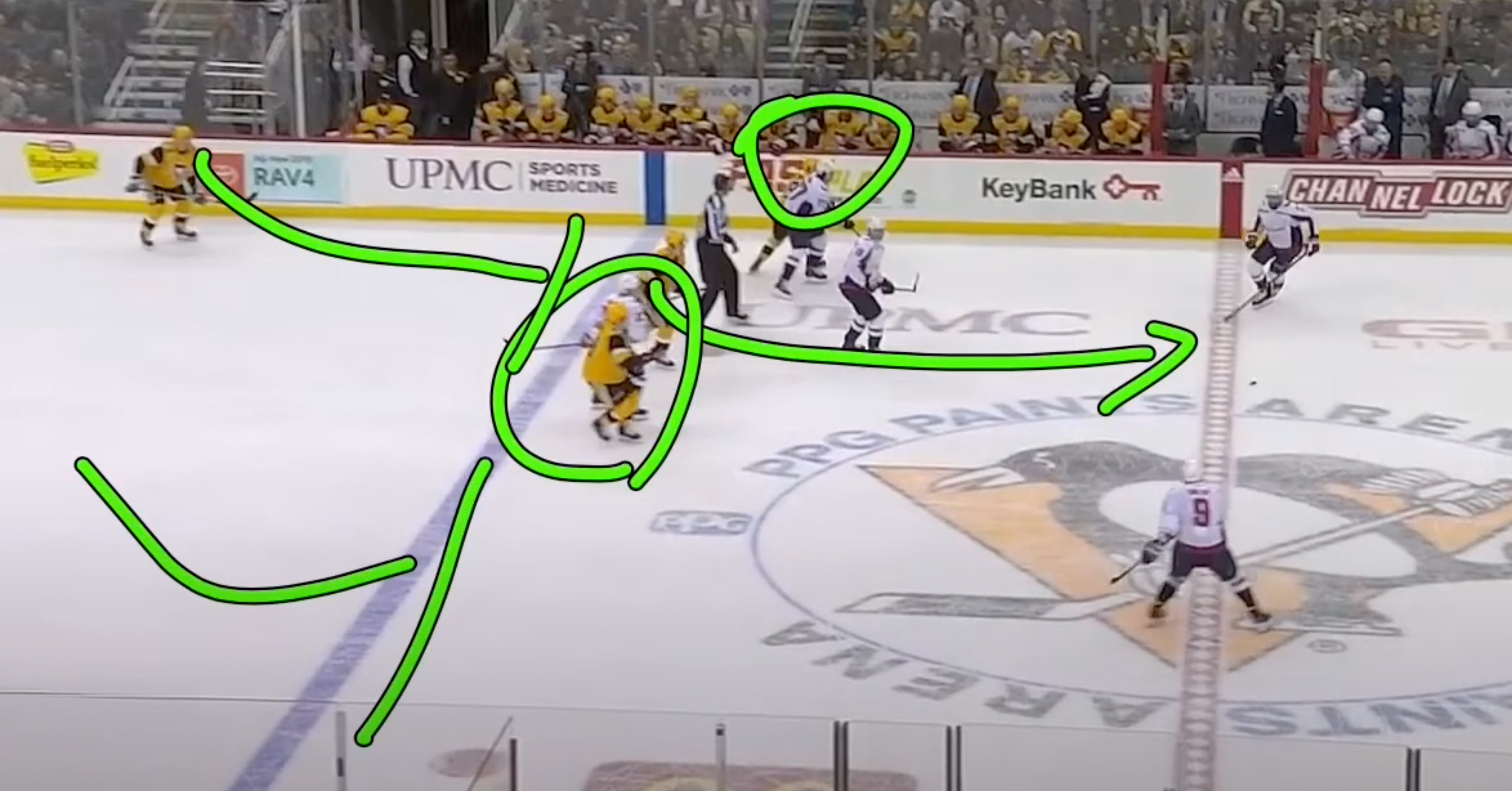

PSB: Puck, Support, Balance is a simple, powerful framework for teaching players how to read the game. Modern hockey is fluid; after a faceoff, traditional positions (LW, RW, C, LD, RD) matter less than understanding PSB roles. All five players operate as a single unit.

I first learned about PSB through a good friend, who had picked it up from one of his own coaching connections. It immediately resonated with a clear, intuitive way to represent support with and without the puck. Compared to other models of positionless hockey I’ve encountered, PSB was easier to teach, easier to apply, and easier for players to grasp.

A key principle within PSB is playing from the inside out. Strong teams control the middle of the ice, between the dot, and force play toward the boards. Whether attacking or defending, winning the interior lane creates better scoring chances, safer exits, and more predictable defensive structure.

Additionally, PSB is strengthened by teaching players to surf and angle. These skills support “north hockey,” where teams move the puck up ice quickly, apply forward pressure, and maintain momentum. Surfing and angling help players close space efficiently, guide opponents into poor decisions, and transition rapidly from defense to offense.

Teams I coach often hear me say, “I want to see fast exits, fast entries.” That’s short for exiting the defensive zone quickly and under control, then entering the offensive zone with speed and structure. The initial rush should be quick and decisive, if a goal isn’t scored, quickly re‑take possession, play keep‑away, and manufacture scoring chances through offensive zone support play. I always stress that windows of opportunity for passing, shooting, and moving into support close quickly, so players must make decisions at a rapid pace.

PSB WITH THE PUCK (Offensive)

Offensive play is defined by who has the puck and how the other four players create options.

-

Puck Carrier (1st Attacker):

Keep eyes up, take available ice, and constantly scan for passing or shooting opportunities. Attack through the middle lanes when possible playing inside the dots creates higher‑quality chances. -

Support:

Move with urgency to become an option in front, beside, or behind the puck carrier. Close support is essential. Supporting players should work from the inside out, staying connected through the middle before spreading wide.

Balance (2nd–5th Attackers): Maintain spacing and structure:

-

No more than three players on one side

-

No more than two players below the dots

-

Maintain presence inside the dots before drifting outward

Player Keys: Communicate, face the puck, scan constantly. Sometimes the best support is staying put to become an option.

PSB WITHOUT THE PUCK (Defensive)

Defensive play is defined by pressure on the puck and maintaining structure.

-

Pressure (1st Defender):

Hunt the puck with urgency. -

Eyes = Containment

-

Backs or Bobbles = Aggressive (close space, disrupt)

Pressure should come from the inside out, steering the puck carrier toward the boards. -

Support:

Assist the 1st Defender while still covering another player. Support defenders should angle and surf into lanes that protect the middle, forcing play north and away from dangerous ice. -

Balance (2nd–5th Defenders):

Stay with your check or maintain body contact.

Keep no more than three players below the dots.

Maintain inside positioning; protect the house first, then expand outward.

Player Keys: Sticks in lanes, urgency on loose pucks, disciplined positioning. Surfing and angling help defenders maintain north pressure and guide opponents into predictable routes.

5. Age‑Based Progressions

Player development follows predictable stages, and practice design should evolve as athletes grow physically, cognitively, and emotionally. While the core principles of repetition, foundational skills, and PSB remain constant, the way these elements are delivered must shift to match each age group’s capacity for learning and decision‑making.

6U–8U: Building the Base

Heavy repetition, simple games, and basic PSB roles form the foundation at this level. Use 4–5 consistent base games to create familiarity and confidence. The focus is on movement patterns, puck interaction, and understanding the simplest PSB concepts primarily the 1st Attacker and 1st Defender roles.

10U–12U: Core Progressions and Stretching Skills

Players at this stage can handle more structure and begin operating in the Stretch Zone more consistently. Introduce constraints such as limited space, time pressure, or added opponents. Begin teaching Support and Balance, and connect foundational skills with small‑area decision‑making to help players link technique with game‑like situations.

14U & Up: Tactical Variation and Game Transfer

Older athletes are ready for increased complexity, speed, and problem‑solving. Use configurable drills to simulate controlled chaos that mirrors real game situations. Emphasize PSB transitions, surfing, angling, and applying skills under pressure. The priority shifts toward game transfer, turning practiced habits into instinctive, in‑game execution.

Coaching Takeaway

When players are improving their skills, staying engaged, and understanding their roles, the system is working even if the drills look similar week to week. Consistency is not stagnation. It is the science of controlled stretching, the foundation of hockey IQ, and the most reliable path to long‑term development. Foundational skills, reinforced every practice, ensure that this growth is built on solid ground. I believe this model not only creates that foundation, but also elevates players’ hockey IQ, confidence, speed, and urgency… The qualities we want to see every time players step into practice or a game.