It's a quality that elite players have and that ordinary players lack.

A research paper by Jan Lennartsson, Carl Lindberg, and Hall of Fame defenceman Nicklas Lidstrom entitled Game Intelligence in Team Sports piqued my interest recently and is worthy of a read. The research deals with the elusive quality that elite players have and that ordinary players lack: the ability to make quick, consistent, and effective decisions.

The paper describes the quality as “being regarded as something incomprehensible… [a quality] excellent players are praised for” and “less obvious than other more tangible qualities (skills).”

I can attest to the fact that coaches often rue over players with large toolboxes but without knowledge of how to use those tools.

The academic authors set out to use mathematical modelling and game theory to create simulations, thereby testing frequently occurring game situations. They then fact-check the results of the simulations by leveraging NHL veteran Lidstrom’s insights, earning the former Detroit Red Wings defenceman an author’s credit for his work.

All open-ended invasion type games are dependent on the ability for players to make reliable real-time decisions. Despite the chaotic nature of play; positional responsibilities, roles and derived tactics are required to establish control over the chaotic. This fact allowed the authors to use math and theory to predict, simulate and single out the best decisions.

A zero-sum starting point was established so that the mathematical model could work. The rules were, “no advanced knowledge of one another” and a defined goal to defend against the opposition, preventing goals against first, and then attempt to score as a second condition. The authors also equalized competing teams in terms of skill. By doing this, the algorithm could examine potential in a variety of game situations. Amazingly, the mathematical models and Lidstrom’s decisions matched.

In the study, the researchers were able to answer questions like: what results in a change in puck possession in a one-on-one situation and is it best to pass often and early or just when under pressure? They were also able to answer questions like: is it best to carry the puck up the ice into scoring areas, as well as where and how should a shot be made to score?

Of the many interesting findings of this study, it was determined that an optimal or well-executed strategy does not always guarantee victory. Players can execute individual, group, and team tactics with little error but not see success. We call this “puck bounces,” or just plain bad luck. But, in the world of game theory, this outcome suggests random variation and a known limitation to experimental design. The finding — our preference to win every time we lace up — isn’t realistic.

On the flip side is the conclusion that teams who do not follow a chosen set of tactics or strategies have only a marginal chance of winning.

“A strategic game is a choice where the participants make their decisions simultaneously… To have a chance, structure must exist and an understanding of strategy must be known.”

Therefore, coaches need to teach, lead, and adjust strategy to create an opportunity to win.

The study also provides proof that the best defence is to make offensive options the poorest. And proficiency in defence is a predictable, patient, and purposeful approach. This largely involves deflecting the attack to the perimeter of play.

Think Lidstrom: purposeful, patient, deliberate, and effective.

Isolating and slowing the attack creates evidence of disadvantage by (defensive) numerical advantage, ie. what we now call defence support. When executed on the ice — and in the theoretical model — positioning in relation to the net and away from high scoring areas, suggest a turnover or takeaway. When limited space and time options are available to the attacker, good defence is assured. Further, the study finds that defensively the greatest effort should be placed on limiting opportunity and access into the zone and into the best scoring areas.

The algorithm also infers that location on the ice is a reliable predictor for tactical decisions. This finding may seem like common sense but a counter-intuitive finding is that off a dump, and in a loose puck situation; a defender is better to not chase but rather “take ice” and hold their position relative to the net. This is because the model sees a foot race and battle for the puck as having a high probability of failure. A critical failure, like a fall, results in an open challenge situation (1 vs 0) and/or immediate numerical disadvantage.

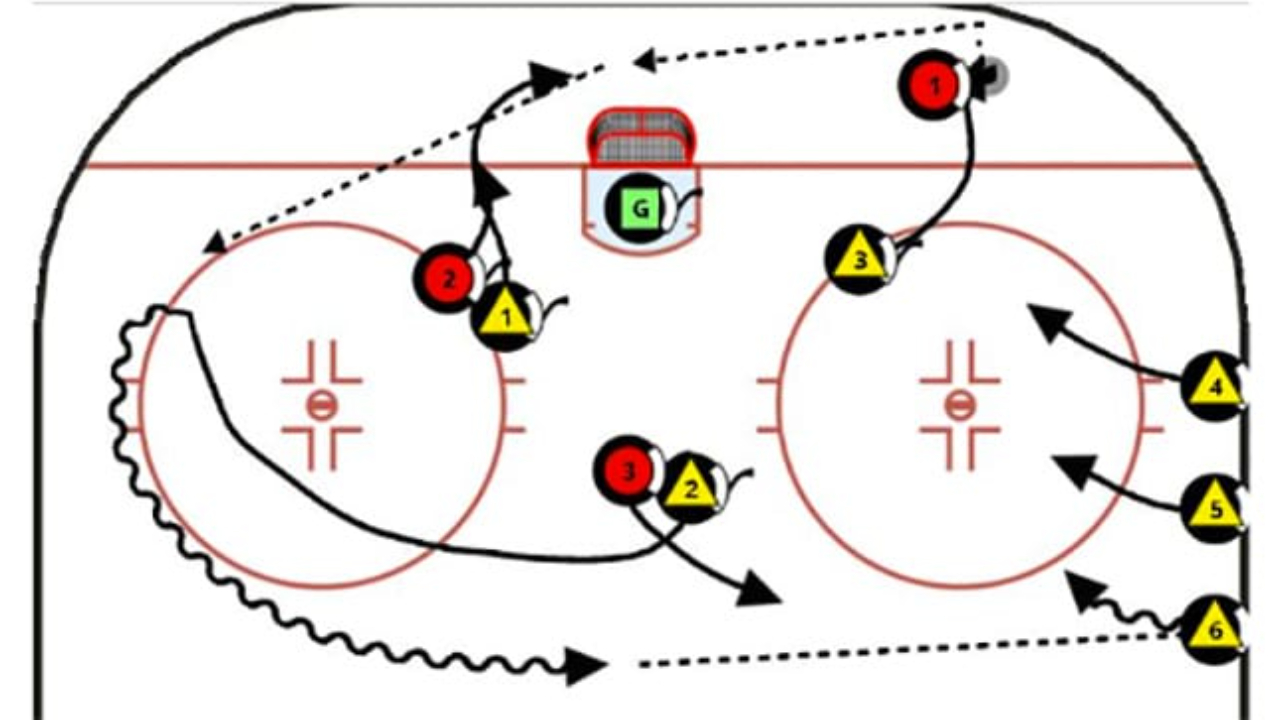

In 2 vs 1 situations, the model confirms success through initial pressure and on-ice proximity to the puck carrier followed by a switch towards covering the other attacker. This S-shaped strategy is noted by the authors to be Lidstrom’s and not how defensive players tend to play the puck carrier in today’s game. In this situation, the model finds the most reliable method is to play a 2 vs 1 as two 1 vs 1s, with the defender taking the non-puck carrier and the goaltender playing the puck carrier to end the play.

On the offensive side of the game, the speed of the attack proved to be most important. In real-world tactics such as winger, centre drive or drive-delay create a chance of beating a defender and/or finding scoring opportunities. Further, the maintenance of puck control, especially on entries, is an important strategy to create offensive potentials. These findings confirm trends we are recognizing in the modern game including Connor McDavid drives, and power play entries where one player carries the puck deep into the zone to set the point of attack.

In offensive drives, puck control and decisions to go 1 vs 1 are found to be dependent on the gap between the defender and the attacker. The relative positioning between the two players as well as the assertiveness of the defender are vital cues. If a shorted gap exists and/or the defender aggressively pursues the puck carrier a deke or move and skating it out was mathematically confirmed as best. However, if the gap is appropriate and the defender is laying back then the 1 vs 1 predictably ends. The reliable choice for the attacker when a defender maintains gap is to change speed and direction by skating away or passing to a teammate. The model also suggests to “pass often and pass early.” Passing often and early was shown to overwhelm.

In terms of shot potential, the lowest chance of scoring and the greatest chance of a turnover is when attackers were steered and angled into locations away from the net. They found that “besides the skill of the shooter the probability of scoring depends on the distance to the goal and firing angle.” A more central and close position is desirable and two possible scorers, rather than one, result in one-timer scoring most often.

Preventing goals from passes across the midline of the slot create “a considerably larger shot potential (with a one-timer) than a shot fired from a player who has puck possession for some time.” The top of the circles, inside the dots, mid-slot, and net-side all seem to suggest optimal scoring locations from one-time shots.

Although this paper is theoretical and reads like a complicated series of formulas Lidstrom’s confirmation and the researcher’s ideas certainly get you thinking about current strategies and what works best.