Introduction

Here are a few coaching phrases that have resonated in the game for decades: “Get the puck deep behind their Dmen,” “I want to hear the forecheck tonight,” “Dump the puck in and be hard on the forecheck,” and “Get pucks deep, keep it away from the goalie, finish our checks, win the puck battles, and get it to the net!” Yes, these phrases are still heard in dressing rooms today, but just like almost every aspect of our game, you have situational decisions to be made. Are the circumstances correct or appropriate for us to forecheck aggressively, or does the opposition have advantages that tell us to forecheck more conservatively and patiently? Using your team’s energy wisely by reading the situation is important. As you will read, this is nothing really new to the game. However, at one time, forechecking was directed or dictated more by the coach based upon considerations such as: “Are we at home or on the road? What is the score? How much time is left in the game?” These considerations still apply today, but it is a continuous, ever-changing game that, to be played well, has to be directed and executed by the players as they collectively, quickly, and hopefully accurately “read” the situation and forecheck accordingly. Competitive, fit, energetic, but smart players are the key to forechecking.

We will take a chronological look at the evolution of forechecking beginning with the 50s–60s to the present day. Some causes of change are due to significant rule changes, but some factors that affected forechecking are rather subtle and definitely had an effect. You will also see that many of the forechecking principles taught in the 50s–60s, and even before that, are still part of our forechecking systems today. The structure has changed with more detail being added, but the basic principles still apply. Please note, to describe the forechecking systems, I will use the North American way, which is to designate the number of players in each layer going from front to back.

50s–60s

Before and during this era, the NHL did have a rule book, but referees were instructed by the league to try to avoid being a factor in the outcome of a game. This impossibility led to some rules being partially applied and some almost ignored. This put referees in a very difficult, compromising position, which lasted until the late 90s and early 2000s. Even today, this fluctuation in subjectivity in decision-making exists, especially in critical moments in the game. This is not meant to be a condemnation of refereeing, as it was and always will be a very difficult job.

From the 50s–60s, here is an example of a rule that was not often applied: delay of game and how it affected forechecking. In scrum situations along the boards in the end zones, regardless of whether the attacker or defender had inside position on the puck, the player was allowed to jam the puck against the boards, stop the play, and get a whistle. In the 50s and 60s, the “dump and chase style” was very common, and it was more a territorial game than a possession game. This meant lots of forechecking moments existed in a game. To reduce the forecheck pressure, the breakout unit at times could simply “freeze” the puck against the boards, avoid a possible difficult forechecking situation under pressure, and the delay-of-game rule was not applied. For the forecheck unit, this “freezing” of the puck too often caused little reward for hard work. To establish a forecheck and then not be rewarded for the effort invested was frustrating. The entertainment value of the game was also greatly reduced. The referee had the discretion to apply the delay-of-game rule, but they didn’t want to be too much of a factor in the game for something that seemed to have minimal effect. This was almost a courtesy “no call” by the officials, granted to both teams, so it was almost decreed to be very fair.

One contributing factor to the dump-and-chase style was the introduction of the offside, two-line pass rule in 1943–44. This meant the long pass from the defensive zone to the far blue line was no longer allowed. This also meant the red line in effect became like an extra defender, allowing the Dmen defending to play tighter gaps in the neutral zone. It also slowed down the speed of the game through the neutral zone and again created an advantage to the defending team’s ability to challenge the attack in the neutral zone. This made possession entries more difficult and promoted the “dump and chase” tactic. It created lots of shoot-in situations, but with obstruction in the neutral zone and the ability to “freeze the puck” in the defending zone, it made forechecking frustrating and not productive, creating turnovers. Thus, the pace of the game became slower and far less entertaining for fans.

In the 50s and 60s, the NHL was a six-team league, and the size of the ice surfaces was not standardized at 85 x 200. As expected, the size of the ice surface had an influence on the style of forechecking, particularly for the home team. The Original Six ice surfaces were: Boston 191 x 83, Chicago 188 x 85, New York Rangers 186 x 86, Detroit 200 x 83, Montreal and Toronto 200 x 85. Generally, the smaller the ice surface, the harder teams would forecheck. Boston, Chicago, and New York had smaller ice surfaces that made aggressive forechecking more effective. Playing half your schedule at home could be a definite advantage and make aggressive forechecking a style of play. Often, both teams would aggressively forecheck in the first period, trying to score first, as this has always been an important indicator for the end result. The home team would hope to score first but felt they had to “put on a show.” Therefore, they would try to add to the score by staying reasonably aggressive and, if successful, put the visitors down a few goals. If so, the home team would then often protect this lead by being a little less aggressive on the forecheck, ensuring they always had numbers back to defend in the middle zone. Also, the visitors would start the game with a fairly aggressive forecheck, and if they scored to get the lead, they would quickly be less aggressive on the forecheck to protect the lead. They had no fans to entertain and therefore no need to “put on a show.”

Roster sizes were set at 16 skaters. Teams would have three forward lines, five defensemen, and two utility players on the roster. The utility players were used in case of injury and special situations like penalty killing. Three lines meant aggressive forechecking was more physically challenging for the players, so forechecking was overall much less aggressive than the forechecking we see today. One must also recognize that the fitness level of players in the 50s, 60s, and even early 70s was not comparable to the fitness levels from the mid-70s to the present day.

In this era, Dmen were primarily considered defenders first and were cautioned on pinching and joining the rush. Only a few Dmen on each team were given more freedom to participate in the offense. Players like Doug Harvey (Montreal), Red Kelly (Detroit/Toronto), Pierre Pilote (Chicago), and Tim Horton (Toronto) all produced offensively while still being considered good defenders. Late in the 60s, with NHL expansion, the great Bobby Orr entered the NHL and led the league in scoring both 1969–70 and 1974–75. In doing so, Bobby Orr created a new template for the “offensive defenseman.” His ability to lead and join the rush was amazing, but his judgment and timing to pinch on the forecheck was also very impressive.

Another factor in the 50s and 60s that influenced forechecking was that the majority of travel was by train. The Original Six being geographically compact allowed train travel, which was fatiguing. With back-to-back games, late-night departures after games, and early morning arrivals on game day, this certainly affected the intensity of forechecking one might use. It wasn’t until the 1967–68 NHL expansion that teams started to use air travel, particularly in the expansion division with teams in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Minnesota, Los Angeles, and Oakland. Other considerations affecting the forecheck were: home-away game, whether it was the second game of a back-to-back for either team, small roster (16–17), injuries, caliber of opponent, score in game, and time in game.

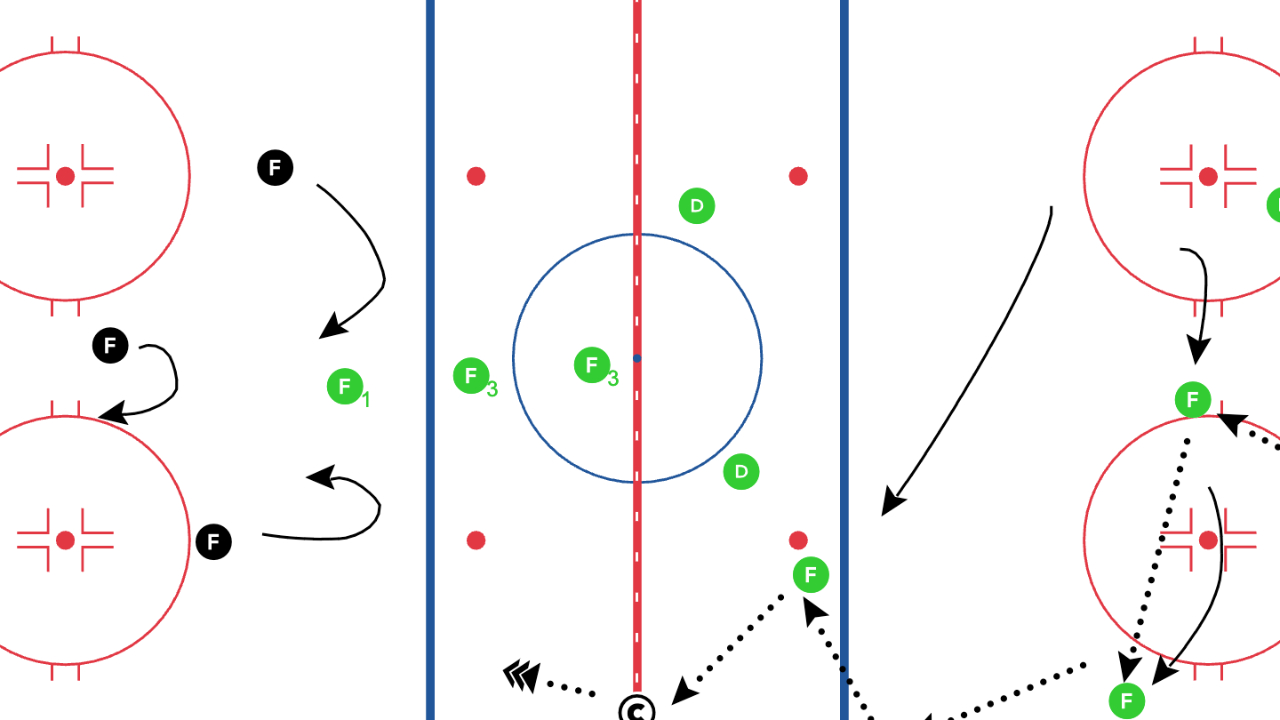

The typical forechecking system was not numerically described as it is today, but it could be considered a variation of a 1-2-2 system. Teams tended to be more patient and defensive, only willing to commit two forwards deep and keep three players back. The best forecheckers were generally your fastest skaters or your best anticipators (game sense). Coaches in the 50s and 60s, and even the early 70s, would describe the forecheck system as: first forward in, take the man off the puck; second forward in, get the puck; third forward stays high in the slot area where you have good scoring position, back-checking position, and covering position for a Dman on a pinch. Dmen had to be smart on pinches: “when in doubt, stay out,” and you must either “get the puck” or “get the man.” This is a very basic overview, but in this era there was no video, so smart coaches gave more information or details. Sometimes these were guidelines, and some were hard rules dictated by the coach depending on the game circumstances.

Coaches didn’t use the term “read”; some used “look.” In practices, they would have five skaters go through a demonstration walk-through on the forecheck, and the coach gave them the looks (tips). F1’s first look: how far away was he from the puck carrier, and could he be aggressive and take the man off the puck? If too far, F2’s first look was to follow and pressure the puck carrier or first pass. If you had stick contact on the puck carrier, you could chase him behind the net; if not, cut up in front of the net. F2, who had depth/separation behind F1 on the forecheck, had three looks: F1’s progress, short-side quick up D-W, and D-to-D pass or wide-side rim. F3, the high forward, had three looks: occupy the middle area high in the zone, rim to the wide side for Dman pinches, and anticipate opposition exits up the wide lane.

Dmen rules were almost rigid: mistakes could be game-changing. No pinching up or down the short side, wide side only if a rim, and make sure to distinguish between puck (“egg”) and man (“chicken”). Pinching without success often led to prolonged bench time. Giving up a 2-on-1 was worse than a 3-on-2. The first rule of defense hasn’t changed much: “Never trust the forwards.”

In the 40s and 50s, some teams designated a high defensive forward at key times against top opposition lines. This forward played high on the forecheck, allowing the other two forwards to pressure. He had to read and use judgment, and a bad decision could incur a coach’s wrath.

An anomaly of the 50s–60s era was the roaming goaltender. Jacque Plante, Montreal Canadiens goalie, would sometimes leave his net to play the puck before Dmen arrived, occasionally negating forecheck situations. Plante’s style was frowned upon by coaches who told goalies: “Stay in your net, stay on your feet, don’t create confusion.” How times have changed.

70s and 80s

NHL expansion continued with new franchises and a WHA merger, providing opportunities but reducing parity. Fisticuffs offered entertainment, but quality hockey was key to gaining valuable TV contracts. Superstars were emerging, but exposure via television elevated the marketing of these players.

The 1979 NHL-WHA merger created parity issues. Two years later, in 1981–82, the NHL had its highest goal-scoring average at 8.01 goals/game. In 2024–25, averages were 6.4–6.5 goals/game. Offensive stars from the WHA—Stastny, Hedberg, Nilsson, Gretzky, Messier, Gartner, Goulet—contributed to scoring.

The 1972 Summit Series highlighted Soviet skill. European forwards were fast, skilled, and mobile. Players like Salming, Persson, Sjoberg, Routsalainen, and Orr created hybrid attacker-defenders capable of shredding forechecks. Puck-moving Dmen like Orr, Coffey, Brad Park, Potvin, Robinson, Savard, and Lapointe influenced transition speed, breaking forecheck pressure, accelerating the rush, joining and finishing attacks.

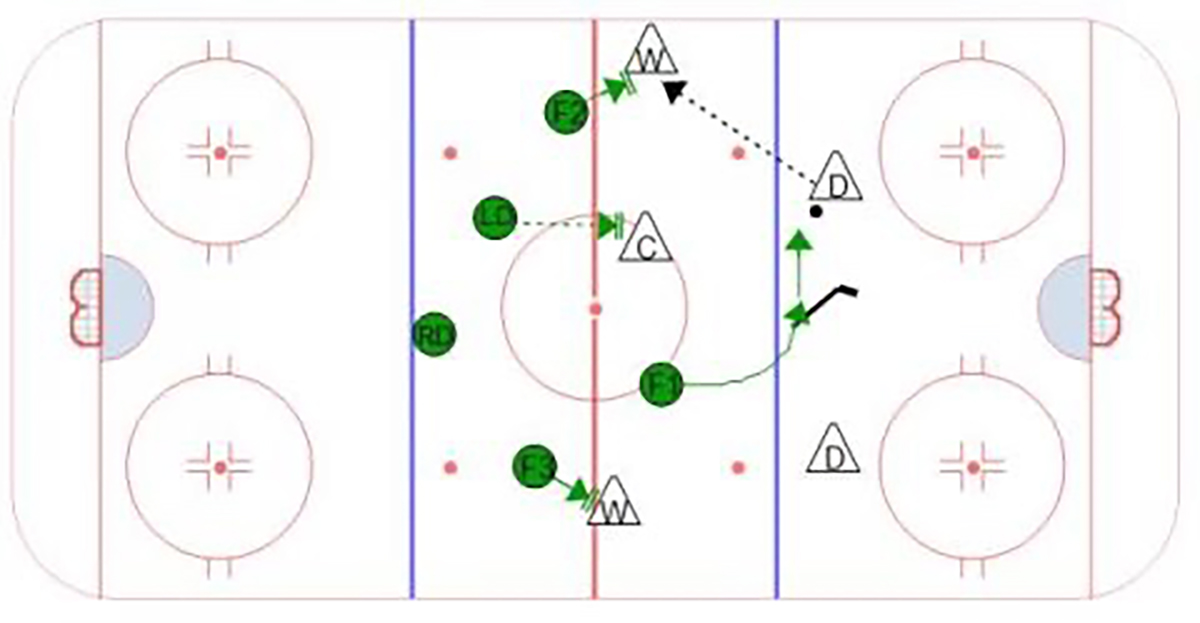

Soviet 2-1-2 forecheck philosophy: wingers as strikers, center as center-halfback, Dmen hybrid role, faced numbers back, regrouped, stretch wingers behind defenders, guaranteed offensive zone entry, 5-man cycling attack. Aggressive split 2-1-2 could suffocate.

Czech 2-3 left-wing defensive system: left winger high in offensive zone, low in defensive zone, worked with Dmen, reestablished three-back. Finns and Swedes competitive vs Soviets.

Backchecking tactics: obstruct, hold up forecheckers, testing tolerance of referees, creating space for breakout, tolerated for ~30 years, increasing offensive chances and fan entertainment. NHL expansion sought national TV contracts.

Forechecking risk-reward: offensive stars entering the game, emphasis on defensive improvement, offensive fluctuations manageable.

1990s–Present

Many coaches use “play not to lose” styles. Numbers back control neutral zone, invite attackers through traffic, create turnovers. Defending team counterattacks with fewer numbers. Mid-late 80s Sweden: delayed/contain forecheck developed (Sandlin, Falk), precursor to “trap.” Systems: 1-3-1, 1-2-2, 2-3, 1-1-3. Teams choose aggressiveness based on separation and situation.

Contain forecheck: NJ Devils 1994–95, trap, won Stanley Cup, success linked to 4–5-back “trap.” Copycat league: teams mimic successful trap. Games could be boring if both teams trap.

Smart coaches: players collectively “read” situations, aggressiveness vs. patience. Goalkeepers active outside net became third Dmen: Brodeur, Roy, Hextall, Smith, Turco. Obstruction allowed, facilitated strategic trap.

European influence: Czech 2-3, Sweden 1-3-1, Finland 1-1-3/1-2-2, competitive with Soviets. Russian player influx in 1990s increased parity. NHL rule changes in late 1990s improved aggressive play. Two-referee system, zero tolerance, smaller goalie equipment, trapezoid rule, larger end zones, removal of two-line pass—all promoted speed, aggressive forechecking, and strategic long passes.

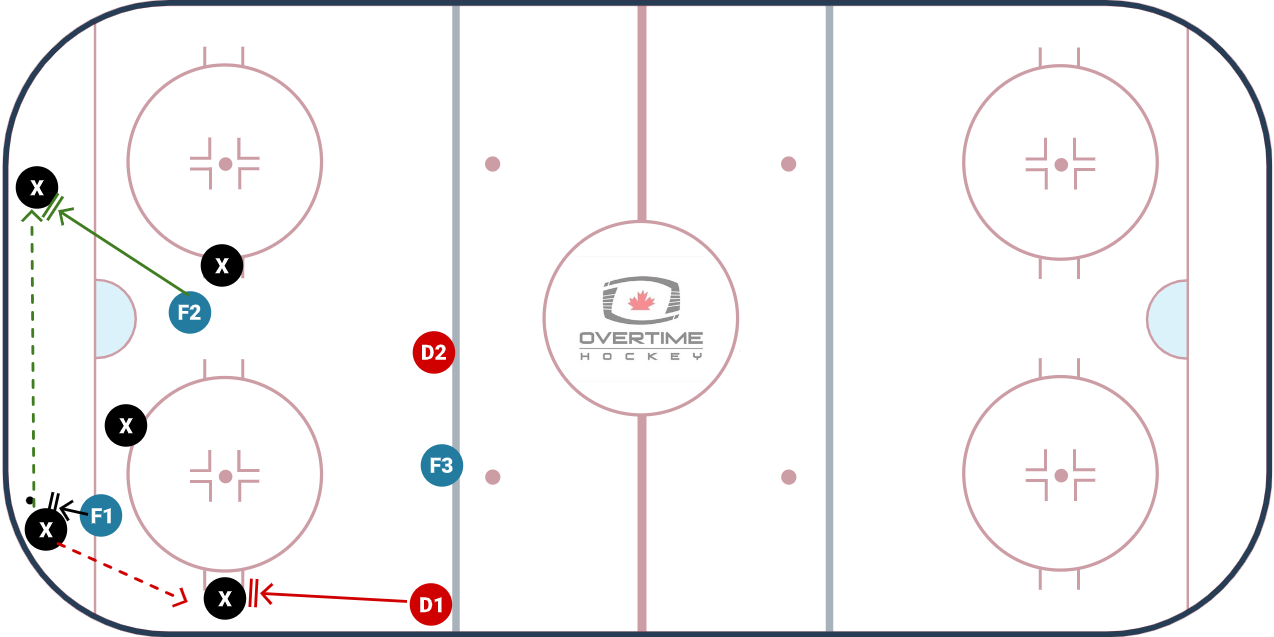

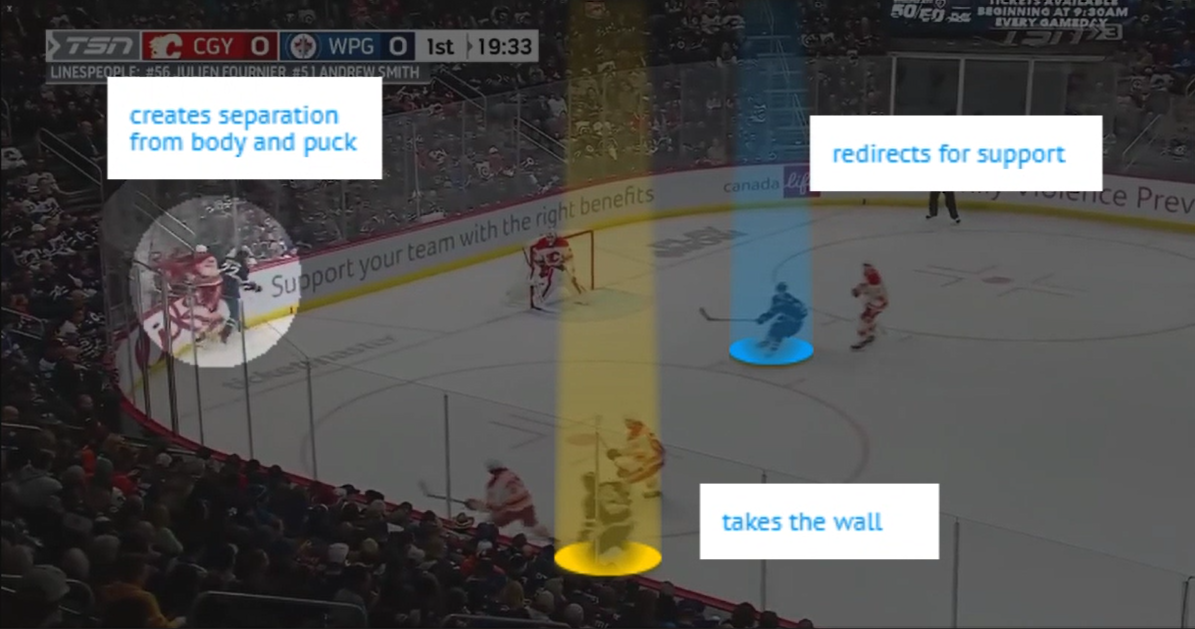

Forecheck systems today: multiple layers/lines adjust together, maintain balance. Players read timing and spacing. Forechecks not only from shoot-ins but puck battles, loose pucks. Quick, reactive decisions critical.

Summary

Most forecheck decisions depend on distance and angles. F1 dictates aggressiveness; the unit adjusts. Anticipating passes allows pressure, recover, and replace sequences. Players achieve multiple challenges against breakout units, forcing errors, skill breakdowns, or bad decisions. Success relies on situational awareness, team coordination, fitness, anticipation, and intelligence.

The principles of forechecking remain rooted in the early NHL era, adapted to modern speed, skill, and rules. Smart, energetic, and tactically aware players are essential, as forechecking is now a blend of art, science, and situational mastery. The evolution continues, but reading the game, applying the correct strategy, and working collectively remains the foundation of effective forechecking.