"Not every kid can be a pro hockey player, but the focus is on the person themselves. If they are willing to work, we are able to do something with them.”

Hockey Factories FREE E-book: A DEEP DIVE INTO THE WORLD’S TOP HOCKEY FACTORIES

***

The 2020 NHL Draft was different.

Different in so many ways.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2019-2020 NHL regular season was stopped on March 12th, 2020.

The playoffs were different, with a 24 team format where you had to go through a qualifying round, just to get into the playoff picture.

The NHL Draft lottery was different too.

The lottery that year featured 15 teams – seven who didn’t make the playoffs and the eight who lost in the qualifying rounds of this new look second season.

Despite having a 2.5% chance of selecting first overall, the New York Rangers slid in to grab coveted Alexis Lafreniere. The Los Angeles Kings jumped up to second, the Ottawa Senators held serve at third.

The draft went as many predicted, Lafreniere first, Quinton Byfield second.

The Senators then took center stage and pulled right at the heartstrings.

Former Jeopardy host, and proud Canadian, Alex Trebek appeared on the screen to announce the 3rd pick of the 2020 NHL Draft.

It would be one of the last public appearances for Trebek before he passed away from pancreatic cancer at the age of 80.

It was just the start for Adler Mannheim’s Tim Stutzle.

Because of the pandemic, there was no march to the podium, no shaking hands with your new coach, general manager or the draft wizards that had selected you.

Instead, Stutzle was surrounded by family and friends in a ballroom in Germany as he pulled the Senators new look jersey over his head.

Stutzle was a Senator, and German hockey was back in the spotlight.

***

You have to go back to 1981 to find a German hockey player selected in the NHL draft, who spent any time playing in the league itself.

Defenseman Ulrich Hiemer (below) was selected by the Colorado Rockies 48th overall in ’81, and played 143 games in the National Hockey League.

After that, it was Uwe Krupp in 1983, a 214th overall pick who made someone look like a genius after he logged 729 games.

Goaltender Olaf Kolzig was the first German to go in the 1st round, being taken by Washington 19th overall in 1989.

Jochen Hecht played 833 games as a second rounder for St. Louis in 1995 and Marco Sturm went to San Jose with the 21st overall pick in the 1996 NHL draft.

Going 20th overall in 2001 was Marcel Goc.

***

Goc knows a few things about what it takes to get to the NHL.

The Calw, Germany, native suited up for 636 NHL games with San Jose, Nashville, Florida, Pittsburgh and St. Louis.

The best success of his career came in the later stages, when he won a silver medal with Germany during their Cinderella run at the 2018 Winter Olympics, beating Canada in the semi-finals before losing to Russia in the Gold Medal game.

He followed that up with his first DEL championship in 2019 with Adler Mannheim.

“I came back and wanted to win a Cup in the DEL, my brothers had already won a Cup, so I couldn’t finish my career without one of those,” Goc jokes.

After hanging up the skates, Goc has since transitioned into a new role with Adler Mannheim.

He is a newly hired development coach, a job he is still getting used to.

“My job now is trying to take care of our under 23 players,” Goc explains. “I try to work with them in separate ice times or after team skates and we try to fill those spots with guys from our U20 team. I’m in touch with the coaches in the program and who is coming through the ranks.”

“I don’t have a team, but I spend quite a bit of time at the rink. My part is still developing, a development coach is not common in Germany.”

Goc wasn’t very familiar with what a development coach’s role even was, until a former teammate became his.

“I got introduced to the idea when I was in San Jose with Mike Ricci,” Goc shares. “Ricci retired and all of a sudden he was a development coach. But it was good for me. Sometimes he was on the ice and sometimes he wasn’t, but I could always ask him what he thought of my game, what I could do better and on the ice we would always work on certain stuff – net front, faceoffs, stuff along the boards.”

“I wanted to be with every age group because I really had no idea what our kids looked like compared to other teams – what are they missing, how you coach them, how to talk to them and try to get the same message across, but you’ve got to approach the players different.”

***

The Club

Adler Mannheim is the New York Yankees of the Deutsche Eishockey Liga.

Since the league began in 1994, Mannheim has eight DEL championships, winning four in five years between 1997 and 2001.

Backed by the Hopp family (Dietmar Hopp, the billionaire software engineer) and the Hopp Foundation, the program leads the way in recruiting players throughout Germany, an investment Marcus Kuhl says is the main reason for their success.

“It is because of the Hopp Foundation that we have the money and possibility to do all these things,” Kuhl, the assistant general manager for Adler Mannheim’s feeder program, believes. “We can hire good coaches, go to the schools and bring these kids on the ice and help them out in every situation of their life. To do that you need money and we are very lucky to have the Hopp family.”

The team plays in the state of the art SAP Arena in Mannheim, which along with hockey is the host to handball and hundreds of other conferences and events. It’s also welcomed Tina Turner, Depeche Mode, Madonna and Justin Timberlake since it opened in 2005.

But there is that another branch to Adler Mannheim that is the backbone of where the program’s success has come.

That’s the Youth Eagles.

Jungadler Mannheim.

A feeder program right to Adler, the DEL and, more recently and frequently, the NHL.

With famous graduates like Leon Draisaitl (3rd overall pick to Edmonton in 2014), Moritz Seider (6th overall to Detroit in 2019) and Stutzle, this is where the best young German players strive to go.

“Mannheim was the first one.” Jungadler’s U20 head coach, Sven Valenti details. “When the program started 20 years ago, it just kept growing. The players at this level kept developing and a few made it to the NHL, people start finding out more and more that we have a good program.”

One of the most valuable development tools Jungadler Mannheim has at their disposable is perhaps the most crucial for any hockey player at any age.

“When I grew up, I had practice twice a week and then I played games on the weekend. Now our U20 team is on the ice six times a week,” Goc states. “They have athletic training before or after practice, so it became a lot more professional and organized and from the very beginning of our program, U11 and U13, it’s streamlined, so the next coach is not always starting from scratch.”

“They have daily off-ice work – weight practice together – and that’s different than other club,” Valenti agrees. “Not many junior clubs in Germany have that type of people and professionals we have that are able to work with those players, which has become more important.”

It’s hard to believe ice is difficult to come by, that coming from a spoiled Canadian.

We have rinks everywhere. Sure, the ice time may not be great for the beer leaguers, but it’s available.

There are approximately 38 million people who call Canada home, along with that a recent study found there are over 2,800 indoor ice rinks in the country.

Germany is more than twice the size, with a population estimated at over 83 million.

As for ice rinks, they come in at a grand total of 218.

It’s hard to get ice in Germany.

“I think there are more hockey rinks in Toronto than all of Germany,” Kuhl estimates. “This is a problem for the future because the hockey rinks in Germany are getting older and the towns don’t have the money to build them up. So that means that Jungadler and Adler, we have to work even harder to make not just more players, but good players.”

***

Kuhl is a legend in German hockey.

He played 18 years in Germany’s top league starting in 1977 and has amassed over 1,000 points.

He’s also one of the founding fathers of the Jungadler program.

Now, it’s up to him and general manager Claudio Preto to find the best players in Germany, as early as they can, and get them into the Mannheim program. Ideally growing them through the ranks in Jungadler, playing for the Adler Mannheim program and then moving on to pro hockey in the DEL, the national team or even the NHL.

“When we are looking for players, we are really looking for coordination, skating, big players, fast players and we try to make their skill side better with different coaches every day,” Kuhl says. “We have off ice programs that are really looking for athletics, skill and coordination. It’s especially important on the big ice over here that you are a good skater, with good skills and a good feel for the game.”

While they are in the Jungadler Mannheim program, they will attend school, live in dormitory style residences, and get on the ice.

“Our program is focused on school and hockey. Our philosophy is 51% school, 49% hockey,” Jungadler GM, Claudio Preto includes. “If they can do both, it’s fine. If not, they will not make it in our program. Not everyone can make money playing pro hockey, so it is very important they do well in school too.”

“We work with the schools so they are always getting free time when they need it. They have teachers there that work privately with them if they need to catch up on work because of hockey.”

“We try to make a good human being,” Kuhl adds. “We try to help them on the ice and off the ice to make them a better person and a better player. We have very close contact with the school to help and inform the players and parents along the way. That’s the only way this will work.”

Playing Up

The Jungadler Mannheim program is the pipeline – and there may not be a more proficient one in the country.

Players are getting into the Jungadler program as early as 11. From there, it’s all about development, and one of the greatest benefits those in the Mannheim program have found for young players, is playing with and against the group above them.

“It helps them think the game right and get away from bad habits,” Goc thinks. “Sometimes it’s a good reality check of where they are. They might play with the U20s where the things they do don’t work and all of a sudden there’s an odd man rush and a goal against. It’s a learning experience.”

“For others, there’s a big difference in how their body is developed, so it might be a smaller kid who does really well in juniors and when you put him against the pros it’s almost dangerous because they can’t protect themselves,” Goc continues. “But then you see, he might be ready next year, so you think of using him in a practice next time.”

“That helps a lot when a 16-year-old is playing with 18-year-olds, even if it’s just in practice,” Kuhl agrees. “They go further in their development and their thinking and feeling for the game. I think that is a big thing when you have younger players playing with older players because you’ll see them get used to the speed, thinking the game faster and the earlier we can do that the better.”

“If the competition is not as good, there is a chance for the players to develop bad habits,” Valenti points out right away. “It’s important that we make sure they don’t feel comfortable when they score three goals, but their backchecking or their stick work wasn’t good. We have to take care of that.”

“When they come in, they have to learn how to do their stuff, but in a system,” Valenti goes on. “A lot of times it’s new positioning and a new approach which takes some time for them to adjust to it but, most of the time they get it because they are smart players.”

Battle For Your Spot

Because of the limitations of finding players in Germany, for many coming into the program it is the first time they are playing with others of their skill level.

“I think in Canada there are more referees than we have players,” Preto jokes.

For some, they rise to the challenge, for others, they fall.

That’s all part of the process for Mannheim, to find those who succeed and continue to challenge them.

“When you have players coming from smaller teams, they have a lot of ice time with those teams and are used to doing things themselves because they are pretty much always the best player there,” Valenti notes. “Now they must battle for their spot on the ice, which they never had to before. Now you’re going to be with 18 other good players and you have to earn your spot or your ice time will reduce somehow.”

This is how German hockey players get their exposure. They are always playing for their spot, and in most cases, their next spot.

A U15 player could very well practice with the U20 team if they are short on bodies. They likely won’t break that line-up, but it sets them up for future success.

Those players get the early looks, they get the chance to see what it will take to get to the next level – and so do the coaches.

“You have to fight for your ice time, you have to show the coaches I’m better than this guy and I can do more and I think that helps those guys too,” Valenti comments. “The chance to play in groups that are older than you is so important, see how they develop and grow that accountability.”

There is also a benefit to those who aren’t ready to make that jump.

“This year we had three guys go up to the pro team and play there, which means the young guys have to step up and take more responsibility,” Valenti reminds us. “That is their chance to learn quicker and faster when they get pushed into that.”

Jungadler Mannheim is always looking for their next challenge and because of the aforementioned skill level in Germany, that is normally found outside their borders.

“The league in Germany is not that good, like in Canada, where they have to fight every weekend to win tournaments because it’s all on the same level,” Kuhl compares. “That’s why we have to send our teams to Sweden and Switzerland to play higher levels and better teams in other places.”

And with that comes another big adjustment most players in Germany would not have the chance to experience.

“Each country is different,” Preto details. “If we go to Switzerland it’s a fast game, a technical game. Sweden also. If we go to the Czech Republic, it’s a different style there. But what every game has is the international pride. The teams we are playing want to win for their country.”

“They will play against other European teams just to see where we are at and what other teams look like because we want to be in the mix internationally as well,” Goc mentions. “I think for some it’s very important to see where they stand. Maybe they are more puck skilled than other players and they get away with stuff now that they won’t get away with playing against pros.”

“We’ve also played schools in the USA or in Canada and it’s a great experience for the players to see all those different styles,” Preto says. “And that comes from the support of Mr. Hopp and the Hopp Foundation. It gives us a great advantage.”

“When you travel a lot because our teams played in Sweden or Finland or Canada, that’s what you see,” storied Jungadler head coach Frank Fischoeder says. “We would fly over and show our guys see how hockey is in the world and tell them ‘these guys will take their job if you don’t do it.’”

All I Do Is Win

You didn’t expect to see a DJ Khaled reference in a story about German hockey, did you?

Well, sometimes there just isn’t a better way to introduce someone.

Frank Fischoeder was a head coach within the Jungadler Mannheim program for 20 seasons. He does not know how to lose.

In fact, when behind the bench in his tenure with Mannheim, he won 17 championships.

He’s also been a U18 National Coach and most recently the head coach of the DEL’s Nurnberg Ice Tigers.

“My junior coach said, ‘a pro career will not be yours’, so I worked a few hockey schools and then worked in a few programs to bring in young kids to hockey,” Fischoeder explains. “I was very lucky to get involved with Mannheim. We have great support in the school, support in the community and, of course, the Hopp Foundation. They gave us the freedom to sign a lot of coaches, made the great facilities and have made this a pretty optimal place for hockey in Germany.”

“Frank was a great coach for me, I played when I was 15 under him and he wanted me to get better every day,” Stutzle recalls after a Senators practice. “When I had a bad game, he was really hard on me, which I really liked. In the end, he was one of the best coaches for sure and they can really thank him for their success. He always made a really good team and we had two years when we won the Cup there, he built some great teams.”

“It’s a philosophy thing. We always believed in our development,” Fischoeder says of the Mannheim program. “There is no player allowed to play with us that is not also doing something else in school, learning a job, having a business, using their head because it’s not different the way you are in your regular life and the way you are as a hockey player.”

“We started out with the same philosophy, so every organization supported by the Hopp family and their foundation works hand-in-hand with the school and mental and personal development,” Fischoeder says. “The money is not that big that when you are done hockey in Germany, you will still have to work after. So, this is not the end of their life, and that is why the school is still important for them.”

Claudio Preto and Marcus Kuhl credit Frank and others for that.

“Our coaches are looking for good attitudes, kids that are willing to work and develop,” Preto says. “Our coaches are responsible for the kids that we bring into the program. Not every kid can be a pro hockey player, but the focus is on the person themselves. If they are willing to work, we are able to do something with them.”

“It’s really hard to make sports on a high level. For us, it’s very important they finish the school with good marks, and we have a good relationship with the school, they make everything possible,” Preto continues. “If a guy does good at his studies and is a good player, we’ve done a great job. If they end up playing DEL or NHL, then that’s a big thing and we are very happy.”

At its core, Fischoeder’s coaching philosophy is not anything dramatically different than coaches you are likely around.

Maybe it’s the style of game in Germany that makes it so unique, or maybe it’s the lack of players to pick from, but Fischoeder’s toughest job is pulling the best out of his players and he does so by going right to the source.

“The ideas I’ve had, I tried to get players involved, get them into the discussion,” Fischoeder states. “I ask what kind of system they want to play, but in every system, there is a grey area. I’ve coached guys with 700 NHL games under their belt, so you can go to him and get his experience, get his feeling.”

“When you have this development, we try to build it and teach the game and give players the responsibility to work into the system. You get into an honest, open conversation with players, they want to play a certain way and you can’t have them leaving the room saying this way would be better. So, we have that conversation, we clear it out and if you make sure I like it, then I’ll say ok and we’ll do it.”

And he uses all the tools he has to get that point across.

“We show everyone on video and it’s played again and again and again and you take the grey areas away so a player cannot come back and say ‘you didn’t show us that’,” Fischoder comments. “This is something I still have problems with because I don’t want to be the coach that dictates everything, I want effort, I want work, I want discipline. I can freak out if something isn’t working but at any level there should be a certain amount of honesty.”

Fischoder uses video a lot and brings his players along, just like everything else.

“One thing we like to do is have the older guys explain the systems to the younger guys,” Fischoder divulges. “We will have team meetings where one line will have to explain one type of system on video, cut the video themselves and present it, learn to speak in front of the team. We always talk about leadership, but leading needs to be taught.”

“During the pandemic, I would put a period into the cloud and would tell them ‘in the defensive zone give me three bad to good clips and explain why,’” the veteran coach explains. “This was weekly homework, they would send their cuts back, they can draw in it, write in it and teach the game that way to see what they see. It’s always different what you see and how they feel it, so this was a good adjustment and the guys had a lot of fun with it.”

Once that is drilled in, Fischoeder and his coaching staff go to work.

“When we get on the ice, it’s principals, but not just straight rules, it’s more read and react.” he explains. “We play half ice and then with U13 we play partly on the whole ice. It makes no sense if you have one good skater, he will kill everyone. He will score five goals and everyone else will get frustrated, so if you play 4-vs-4 in a small area, the only rule is you have to skate, this is something that is hard of the classic coaching style of making systems and rules and giving that framework, but we have to get rid of that even more.”

“That style did everything for me,” Stutzle reflects. “They played me a lot, wanted me to play with the best players, gave me PP minutes, gave me confidence to play my game and that’s what really helped me. They wanted me to get better every day in practice and it was really good for me.”

Fischoeder is Sven Valenti’s predecessor.

Valenti climbed through the ranks, starting as a U13 junior coach when his son was invited to the program. He moved up to U17 and last season got his chance after Fischoeder left.

“Coaching here, our workload is high compared to other teams because we are trying to get to the international standard that we need to be able to match to the top programs in Europe,” Valenti starts. “Our teams are really active, we are practicing that a lot. We want our teams to put pressure on other teams. We don’t want our players playing like robots, we want them getting used to finding solutions in different areas and different times. We don’t want them to have Plan A, Plan B, Plan C and if those aren’t open, they don’t know what to do.”

Coming in after such a legendary coach does not go unrecognized by Valenti, who admits he’s learning every day on the job.

“it’s great to have good coaches here for feedback and what do they think of this and that,” Valenti admits. “Marcel (Goc) is such a professional and is so down to earth. He just enjoys working with the kids that are here and having fun.”

“You should never be too old to learn, there’s no reason to be arrogant and think you know everything because you can learn from a U9 or U10 coach or practice because if it’s good, why not take it.”

“I think we are more structured, and we need to be because of the big ice,” Fischoeder says. “There is so much more freedom now for players. At the beginning you had a lot of scoring young players that were supposed to block shots and play defensively and then everyone was wondering why they couldn’t score anymore, so now guys can skate around and back check like Leon (Draisaitl) in his first years – not at all.”

Coaching The Best

“It’s always fun. I don’t know if it’s like this in North America, but I’ve heard coaches that would say ‘I made this guy,’ like hell you did. We were lucky, we had this talent in our hands, we didn’t destroy it.”

Fischoeder speaks highly of his time with Leon Draisaitl.

Draisaitl, a Koln native, played 40 games with Jungadler Mannheim, scoring 57 points and adding 12 more in eight playoff games.

Kuhl agrees they didn’t do too much with Leon, other that let him go.

“Even the best players, like Draisaitl, you don’t have to show him a lot when he’s 16 because you could already see what he could do, but what he got from us was extra ice time and extra coaching to help him develop.”

“Same with Seider,” Kuhl continues. “When he was 14, he was practicing maybe twice a week, and when he came to us he was able to practice twice a day. You could see how fast he developed and even now you can see how he’s getting better every day. What he has done in the last 5 years has been unbelievable.”

“I remember when I first travelled to Canada, (Sidney) Crosby was still playing in Rimouski and there were 10,000 spectators waiting to see this guy play,” Fischoeder recalls. “Everyone knew this kid was the next Great One, but if you see these kinds of players in your organization, your job is not to destroy these guys.”

“When I see Leon, we still joke around about his backcheck, so when he was with us he knew exactly what he needed to work on,” Fischoeder continues. “It was a pretty easy job as a coach. Let them play and enjoy and pressure the other guys to support their development by working hard against them in practice.”

Players at Jungadler Mannheim also have Goc’s 600+ NHL games to reflect on, including suiting up with Crosby in Pittsburgh.

“He is a great example,” Goc states. “When he goes out on the ice to practice, I was just like ‘wow, he works in practice.’ He’s not just waiting for the coach to blow the whistle and get off the ice. He does every drill right, when he goes to the net he wants to score and that’s what he does in the game as well.”

“He puts the work in in the summertime and during the season so I tell my guys I’ve seen this guy do it,” he says. “You’re good right now but if you want to make it to the next level you have to keep doing it and don’t be satisfied with where you are right now. Somebody else is going to put in the work and they will roll past you at some point.”

The time Draisaitl or Seider or Stutzle spent there will have an impact far longer than their actual games played in the program.

“Draisaitl is pretty famous now, since he won MVP people know a lot more about him,” Valenti admits. “Of course, we have soccer is Germany that is the king of sports, but now we are seeing hockey players and basketball players playing pro in North America and it’s nice to have.”

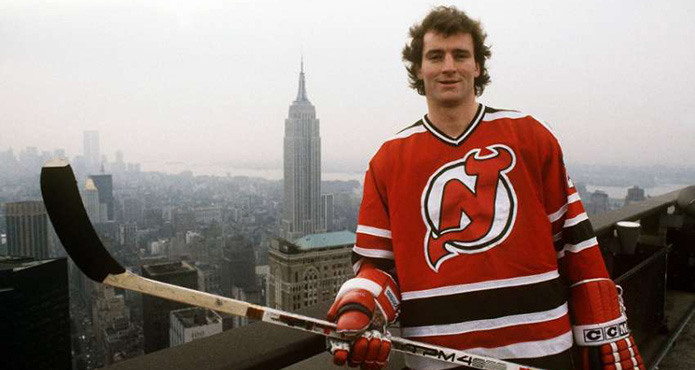

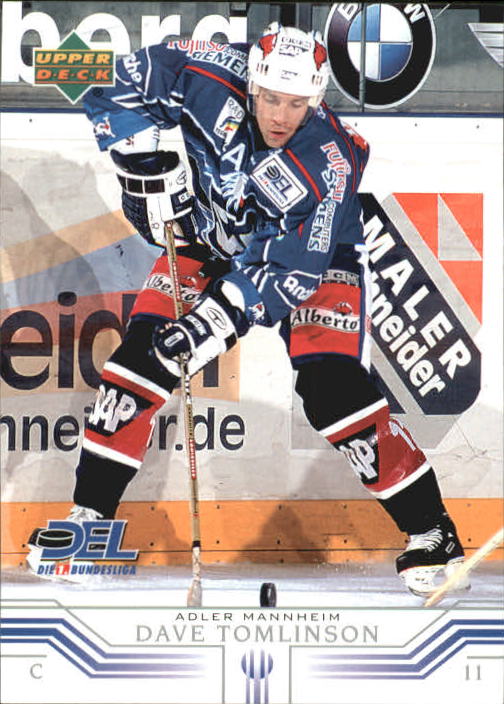

“You get a couple guys like Seider or Stutzle who lead the way and you see a bunch of other kids that want to follow,” reflects Dave Tomlinson, a German hockey hero in his own right. “For young German players they have more players for them to look at and follow, along with doing so well at the World Juniors and the World Championships that has sparked that on.”

Tomlinson spent six seasons with the parent Adler Mannheim program, after a career in North America that included stints with the Toronto Maple Leafs, Winnipeg Jets and Florida Panthers, along with over 340 AHL/IHL games.

Tomlinson, now the colour commentator for the NHL’s newest franchise, the Seattle Kraken, will remember his time with Mannheim well.

“I loved it there. Mannheim was really well run, it was run as close as you could to an NHL or minor pro team,” Tomlinson shares. “I realized if you score early in the season, you’re a fan favourite and every top team will be after you. The Germans fans are really passionate. They love their chants and songs so they will create a song for their star players. My song was a take off of ‘Mrs. Robinson’, they would sing ‘score a goal Mr. Tomlinson’, so you’d have 11 thousand German fans singing and banging on drums so how does that not make you totally pumped?”

Fischoeder will take no credit for anyone or anything. He doesn’t even give himself many props for his 17 championships, including a story when he left the rink right after winning a championship to play soccer with his daughter.

But it’s not just the players Fischoeder points to as the rising stars in Germany.

Marcel Goc gets high praise from everyone I spoke with, a rising star in the coaching ranks in Germany, if he wants it.

“Marcel is such a good guy, such a hard working guy,” Fischoder praises. “I have not met a lot of pro players who are that focused, that professional, his preparation for practices and I tell him all the time, you don’t know what kind of power you have in German hockey, if you want to be the #1 guy you can do that in two-to-three years. You can make a big difference.”

***

The Challenge

“Our big problem in Germany is soccer,” Valenti says unequivocally. “With soccer you just need shoes and a ball, and you can play almost anywhere. In Germany, hockey is pretty expensive, and we don’t have the ice available for them.”

“We are trying to recruit more players. In the top league they have recruiting programs where at the games they give kids 7, 8, 9 years old the chance to go out on the ice and have a “day in the life” with the club,” Valenti shares. “We are in the schools, we will go into kindergarten, and we bring them on the ice, teach them how to skate.”

“The program German Federation changed for junior hockey. Even if you are in the smallest city and have an ice rink that’s just for fun or you’re in a professional league, there’s a guideline of what to do,” he continues. “We have the development program for coach’s standard is getting higher and higher and now we have more and more players coming to the NHL, so there’s a chance with social media you have a chance to see all those players and for young kids they have these heroes now helps a lot.”

Tomlinson knows how hard it is to get German players, from his time playing overseas. But from where he’s standing now, he sees the growth continuing.

“I think the new buildings have been awesome and that they are building new arenas. It seems like the top teams continue to be the top teams, but I do think Germany itself is making a good argument for being considered amongst the Finlands, Swedens and Czech Republics because they have more depth and more ability to compete with some of these bigger countries.”

For Fischoeder, it’s simple.

“We need more players. It’s too expensive here for skills coaches in kids hockey,” he admits. “You can play soccer for 60 euros a year, you get support from the German Football Association, so for us there was always this important thing of having the duel system where we are helping with the school and the hockey.”

After The Game

“If you are a national team player in Germany and you do nothing wrong, you have no injuries, everything goes perfectly and you have a great career, you maybe have your house paid for, you maybe have a million euros on your bank account, but that doesn’t mean you won’t have to work the rest of your life.”

Fischoeder, along with everyone in the Mannheim program, doesn’t waste any time to introduce the idea that not every player in the room is going to make the DEL.

“There’s not too many big hockey towns around Mannheim, so the range of area from where kids come from is fairly big,” Goc explains. “The combination of school and hockey, making sure both are good for the players is structured really well here and that’s one thing as a parent you’re looking for.”

“The main work is taking care of the person and their personality development,” Fischoeder praises. “When you work in an organization like this it’s taking care of people, hockey is important but more important is the responsibility you have that these kids feel comfortable.”

“You never know, if the hockey part is not where they end up going with their career, you don’t want to end up with nothing,” Goc confirms. “In case hockey doesn’t work the dual development making sure they are set with school and have good grades and preparing them for life, essentially, outside of hockey. How they treat hockey is how they will treat everything.”

Fischoeder has billeted several kids over his time as coach of Jungadler Mannheim. He gave the program 20 years of his life.

“I still come into the arena in Mannheim and hug everybody and feel comfortable after 20 years how much it’s meant to me,” Fischoeder says. “I built a house in Mannheim; I married my wife here and my daughter was born here, so I will always live here. I was 28 when I stepped into Mannheim, that’s a long life here and this is a big part and I love the organization and what they gave to me and the opportunity they gave me.”

“I’ve had a chance to see hockey all over the world and not a lot of people have had this chance.”

“The youth program made a huge difference for me, for sure,” Stutzle beams. “What a great coaching staff and guys like Frank, they just want to make young kids better and get them to the pro team, and that’s what they’ve been doing so far. It was some of the best years of my life being there.”

Stutzle and the rest of the players of Jungadler Mannheim have had the unique opportunity to see beyond their walls. To see hockey in Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Russia, the USA and Canada.

Their greatest gift to us, has been bringing the spotlight back to the blossoming hockey hot bed that is Germany.