From Theory to the Game – Integrating Skill Acquisition Science into Modern Hockey Coaching

In hockey, we often talk about skills as if they exist in isolation: skating, puck control, shooting, puck battles, scanning, decision-making.

In reality, they don’t develop separately. They emerge through action — within a dynamic system where body, mind, and environment are in constant interaction.

Skill acquisition research has approached this process from multiple angles. While the theories differ in emphasis, they share the same fundamental goal: to understand how practice transfers to performance in games.

At Viima Hockey, our training philosophy is not built around a single method or buzzword. It is grounded in a scientifically informed understanding of how humans learn motor skills.

Good theory is not the opposite of practice — it is the foundation of it.

Why Skill Acquisition Theories Matter

Learning itself is invisible. As coaches, we only see the outcome: performance.

Theories help us answer the questions that matter:

- Why does one player improve rapidly while another progresses more slowly?

- Why does a skill look sharp in drills but disappear in games?

- Why doesn’t “correct technique” always lead to the correct decision?

Today, three perspectives stand out for both research support and practical applicability: Information Processing Theory, Ecological Dynamics, and Predictive Processing.

They examine the same phenomenon, learning, from different viewpoints.

For coaches, understanding these perspectives expands our toolbox.

Three Perspectives, One Objective

1. Information Processing: Building Reliable Foundations

Information processing theory views the athlete as a processor of input. The senses gather information, the brain processes it, and the body executes movement. Skilled performance is the successful retrieval and execution of previously learned motor programs.

This perspective underpins structured, repetition-based training — often referred to as deliberate practice (Ericsson et al, 1993).

At Viima, this approach is especially valuable when building or refining foundational skills. Clear technical models, targeted feedback, and purposeful repetition help establish an effective baseline.

However, this is only the starting point.

A technically correct movement in isolation does not guarantee success in a chaotic, time-constrained game environment.

2. Ecological Dynamics: Skill as Adaptation

Ecological dynamics shifts the focus from stored motor programs to interaction.

Skill is not something pre-packaged inside the athlete. It emerges from the relationship between:

- The player

- The task

- The environment

Learning occurs through exploration, adaptation, and problem-solving.

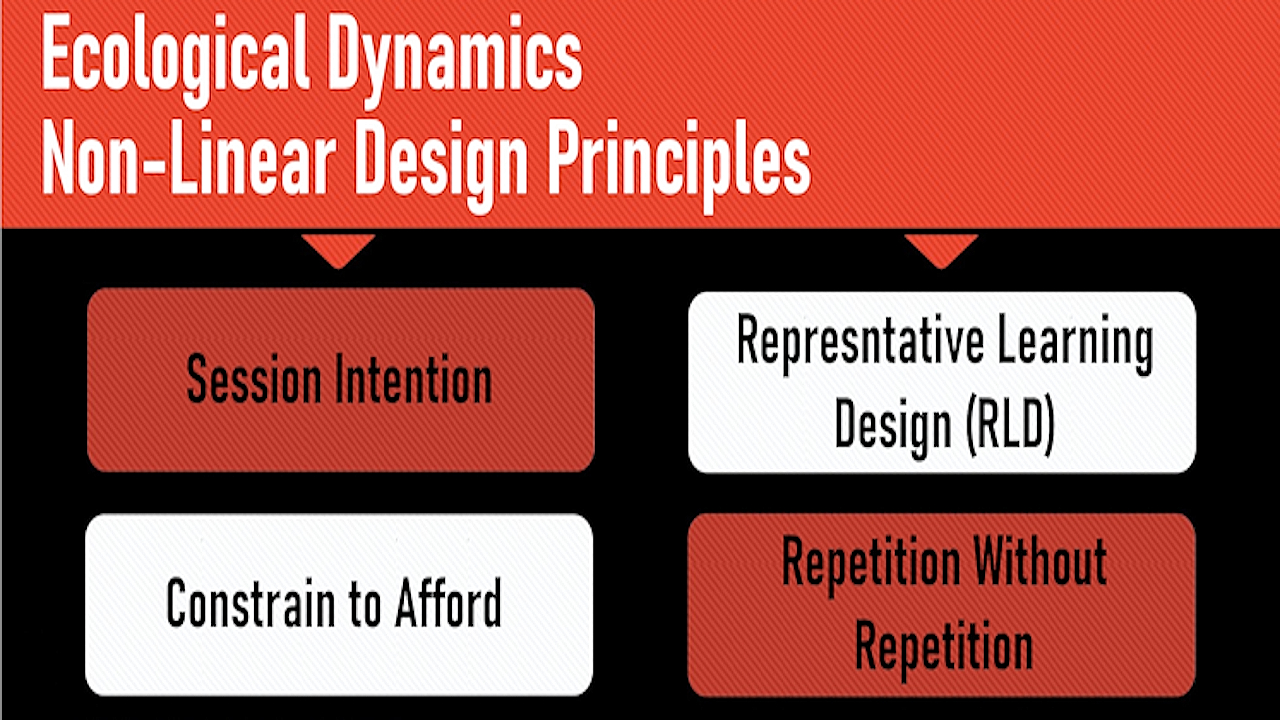

In practice, this leads to nonlinear pedagogy:

- Designing drills with meaningful constraints

- Encouraging players to attune to environmental information

- Avoiding over-coaching and micromanaging movement

- Embracing variability as a necessity, not a disturbance

Players improve when they are required to solve problems – not simply reproduce a model.

In hockey, where no two shifts are identical, adaptability is performance.

3. Predictive Processing: Training the Future

Predictive processing is one of the newest additions to the skill acquisition conversation.

According to this framework, the brain is constantly generating predictions about what will happen next. When reality differs from expectation, the brain updates its internal model.

In hockey terms, this is the ability to:

- Read the play

- Act under uncertainty

- Make decisions with incomplete information

- Adapt instantly to unexpected changes

The difference between good players and elite players often lies here in how effectively they anticipate and adjust.

Rethinking Errors: Problem or Fuel?

One of the clearest distinctions between theories lies in how they interpret mistakes.

- In information processing, an error is often viewed as a deviation from the ideal movement – something to correct quickly.

- In ecological dynamics, errors are essential to exploration and discovery.

- In predictive processing, “prediction errors” are the very mechanism that drives learning forward.

In our daily work, mistakes are not treated as failures – they are treated as information.

But acknowledging the value of errors does not mean abandoning coaching.

Feedback must align with intent.

In some drills, immediate correction is appropriate. In open, game-like environments, the environment itself often provides the feedback. In those moments, the coach’s job is not to supply answers, but to guide attention – through questions, constraints, or video – and allow the player to discover.

That restraint is one of the hardest skills in coaching.

Why We Use Dual-Task Training

Parents and even coaches are sometimes surprised to see a player solving math problems while performing puck-handling drills off the ice.

This is not a gimmick.

Dual-task training – combining cognitive load with motor execution – intentionally shifts conscious attention away from controlling the movement. When the athlete’s focus is directed toward a secondary task, the motor system is forced to self-organize.

Research supports this approach: automated skills are more resilient under pressure, distraction, and chaos.

Hockey is played under cognitive load. Training should reflect that reality.

At Viima, integrating sport-specific motor tasks with cognitive challenges is not an exception – it is a principle.

Past, Present, and Future in the Same Drill

These theories also differ in their time orientation:

- Information processing emphasizes the past — what has already been learned.

- Ecological dynamics focuses on the present — what this situation demands right now.

- Predictive processing is oriented toward the future — what is likely to happen next.

Hockey demands all three.

Therefore, practice must integrate all three.

Do It in the Game

Modern coaching is not about choosing the “best” theory.

It is about knowing when and how to apply each perspective.

- Foundational technique may require clarity and repetition.

- Game-like situations require variability and adaptation.

- Elite performance requires anticipation, emotional regulation, and decision-making under pressure.

The skilled coach understands the theories but does not become trapped by them.

They are tools – selected based on the player’s needs and the performance context.

Ultimately, all perspectives agree on one fundamental truth:

There is no substitute for practice.

Skill acquisition requires time, repetition, and a high-quality learning environment. But practice only has value if it transfers to performance.

Everything must point toward the game.

That integration – deliberate, adaptable, future-oriented training – is the core of modern player development, and our coaching philosophy at Viima Hockey.

____________________________

About Viima Hockey

Viima Hockey is Europe’s leading provider of individualized ice hockey coaching and player development services. From youth players to NHL professionals, we help athletes become the best version of themselves – and perform where it matters most, in the game.

Trusted by top talent and organizations, including NHL players like Miro Heiskanen and clubs such as Jokerit Helsinki, Jukurit Mikkeli, and the Swiss Ice Hockey Federation, Viima offers world-class skills training, skating development, shooting and scoring coaching, goaltending training, strength and conditioning programs, and coach education.

For more information, contact Jarno Kukila at jarno.kukila@viimahockey.com