Passively standing in a high-danger area won’t lead to many goals.

In Game 7 of last year’s Stanley Cup Final, three of the five goals came from one-touch plays near the net. As the series pitted two of the best defensive formations in the NHL, players had to take advantage of the narrowest of openings to score.

In the first period, with a defender on his back, Ryan O’Reilly tipped a shot to end a Blues offensive drought. And in the third period, Brayden Schenn and Zach Sandford attacked the low-slot deceptively to score from far-post one-timers, putting the game out of reach of the Bruins.

The net-front is where shots score at the highest rate; it’s also the most heavily guarded area of the ice. Defensive systems are built to neutralize attacking threats in that zone, but clever attackers can find ways to bypass its barriers to score. They time their arrival to the net with the passes of teammates and the puck is on and off of their stick before the opposition can react.

Offensive timing

Timing is the difference between a goal and a failed scoring chance.

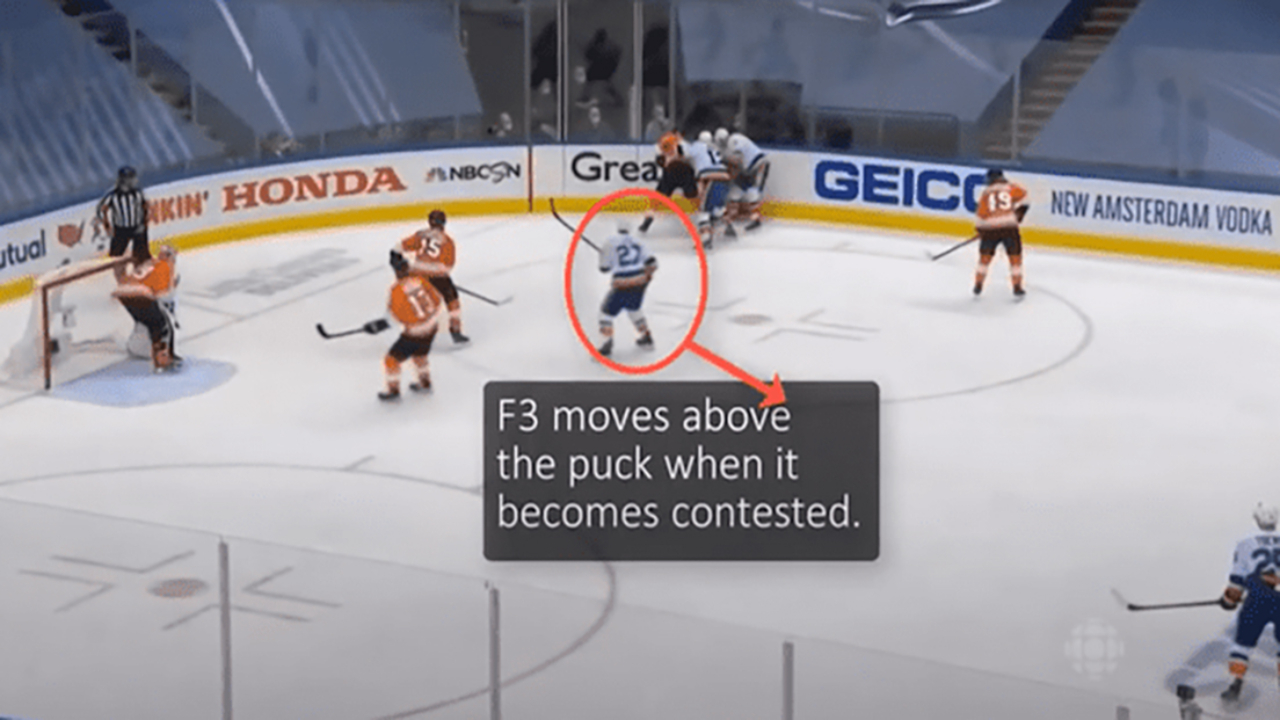

Against heavy defensive pressure, passively standing in a high-danger area won’t lead to many goals. Attackers have to move in scoring spots at the right time — as their teammates become ready to connect with them. If they arrive too early, before the possibility of a pass, they give the defence time to neutralize their stick. If they arrive too late, they miss the play.

As hockey gets more competitive, as defences become more mobile, more structured, more aware, the importance of timing grows. It became a crucial element in the final game of the Cup Final, the driving factor behind most of its goals.

The three sequences above started with some form of on-puck work by the Blues, a team that made intense pressure an identity in the latter half of their season. But St. Louis outworked opponents away from the puck, too. They scanned the ice, hunted opportunities, and supported the play in timely ways.

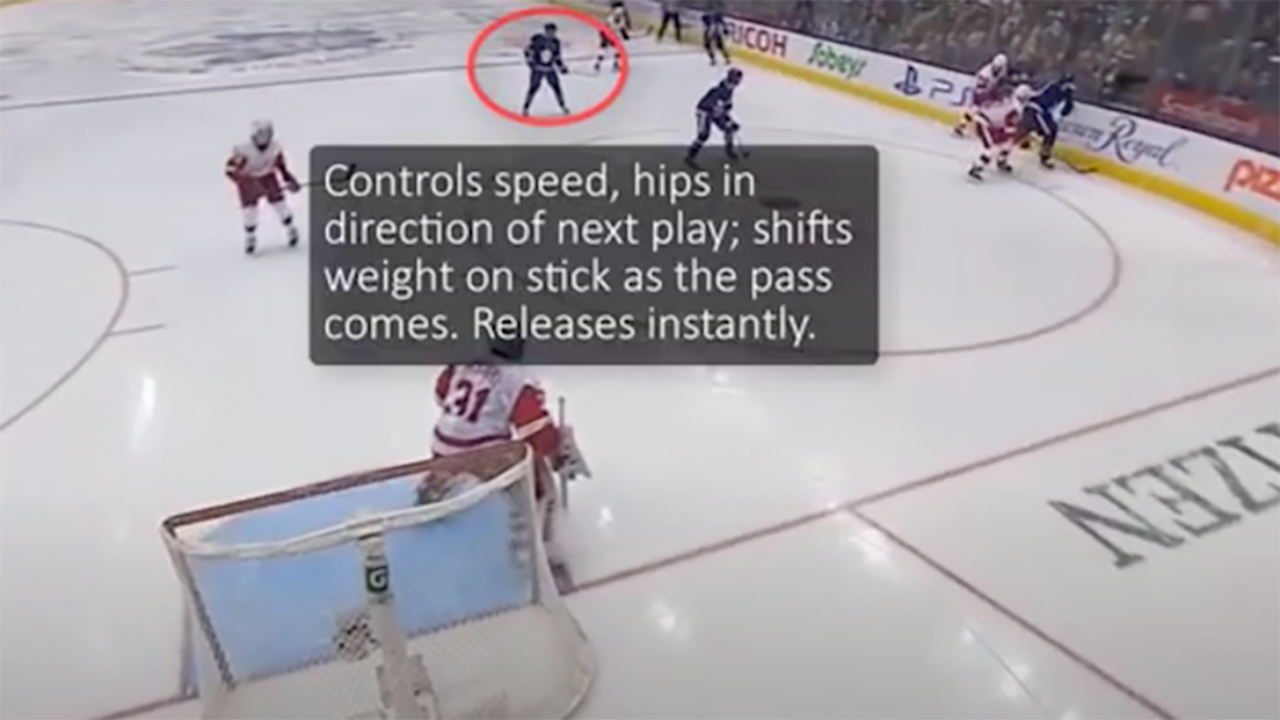

On their goals, Schenn and Sanford came off the bench. They accelerated towards the offensive zone and read the movement of a teammate carrying the puck along the far wall. After crossing the blue line, they controlled their skating, retaining speed to escape a potential backcheck, but slowing down enough to not move into the checking zone of a puck-absorbed defenceman in front of the net.

Schenn received a pass in the middle of the dots and fired. Sanford had to further adapt to the play; he changed speed a second time to arrive at the right time inside a cross-crease passing lane.

O’Reilly also showed great timing on his goal, but in a different way. He battled Brandon Carlo in front of the net and ended up in the middle of the slot as the puck moved laterally at the point. He saw the shooting lane available for his defenceman; he saw that defenceman wind up for a slap-shot, and the deflection opportunity the play presented.

But O’Reilly delayed his move; he kept his stick in a neutral position. Only when the blade of his teammate started its downswing and hit the ice did the centreman shift his own stick to deflect the incoming puck. His abrupt move took away Carlo’s ability to react and disrupt the play.

Timing principales

The best goal-scorers share a few abilities that lead to great timing:

- Anticipate teammates’ plays to the slot and the counter-movements of the defence.

- Choose the best skating route to support those plays, often the deceptive one that brings them behind defenders’ back.

- Change and control speed to arrive in a scoring spot at the same time as the puck.

- Delay shifting their stick to the passing or shooting lane until the arrival of the puck.

Great timing comes from having the right mindset. Players should attempt to read the game one pass or one move ahead as much as possible. When the puck is on a teammate’s stick, they should be picturing the next play, foreseeing how they can best support it, and choosing the right speed and route to do so.

Examples of great timing

In the video below, NHL scorers found great scoring chances by thinking one play ahead and chaining a few of the abilities above.

In the first clip, moving into the high slot behind a defender, Brad Marchand saw Charlie McAvoy exchange the puck with Anders Bjork and head down towards the goal line. As his defenceman levelled with the faceoff dot and looked to pass, Marchand attacked the net, pressed his rear-end on the hip of his checker, and extended his stick to redirect the incoming puck.

Marchand knew that Anze Kopitar, one of the best defenders in the game, was covering him. He waited for the right moment — for his blue-liner to be in a passing position — to drive net-front, establish body positioning, and deflect the puck. If he moved early, Kopitar would have tied him up; if he moved late, he would have missed the pass. But Marchand timed himself perfectly; he left no chance of a reactive defensive counter.

Examples of poor timing

In the following video, scoring chances never developed as the timing of attackers was off. They recognized opportunities too late, chose poor skating routes, and skated into the slot before teammates could pass to them. As a result, defenders easily neutralized the plays.

Timing is one of the hardest elements to assess in offensive sequences; it requires practice and constant mental engagement on the ice. Those who get it right, however, separate from defenders on the ice and from their peers on the scoring leaderboards.