Teaching Hockey Through Concepts, Not Systems: Developing IQ Through Situational Awareness and Team Tactics

Jeff German, Head Coach, Denison University

Playing as One Mind

In the development of hockey players at all levels, particularly at the high school, junior, and collegiate levels, coaches often fall back on structured systems. These systems, whether they be a 1-2-2 forecheck, a neutral zone trap, or a box-plus-one defensive setup, are designed to bring order to the chaos of the game. They tell players where to go and when to go there. But in doing so, they rob players of the opportunity to think. Systems tend to lock positions in place and reinforce a “you go here” mentality. They discourage improvisation and limit creativity. And if we as coaches are serious about developing hockey IQ, we need to move beyond systems and start teaching concepts: dynamic, team-based reactions to in-game situations.

The Limitations of System-Based Hockey

A traditional system, by design, is static. It's a map rather than a compass. Coaches often fall back on system-based teaching because it offers a simple structure, predictability for both players and coaches. Players are told where to go and what to do, often irrespective of what's unfolding in real time. Systems are easy to teach and look organized in drills, and when executed perfectly, they can stifle opponents and minimize chaos. But, hockey is chaos! Teaching a system that functions under perfect conditions misses the point. There are no perfect conditions in a game played at top speed with imperfect players against an ever-changing opponent.

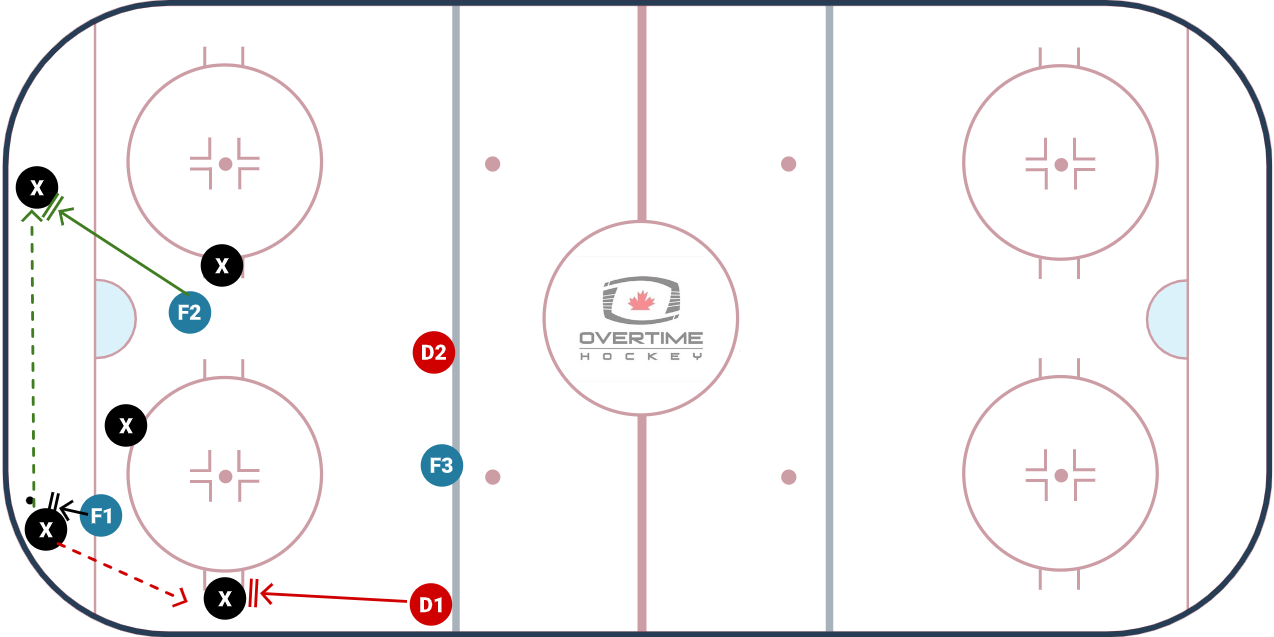

Systems teach roles, not responsibility. The F1 in a forecheck system is told to go deep and pressure the puck, F2 supports wide, F3 stays high. D1 pinches or holds the blue, D2 covers. But what happens when the puck rims hard and a defenseman is closer to the play than a forward? If you’ve taught a strict system, that defenseman will hesitate-thinking, is that my puck? The second of hesitation leads to an odd-man situation, or worse. Why? Because the system didn’t allow for conceptual thinking. It taught positional obedience.

Why Concepts Matter

A better method, one that cultivates hockey IQ, confidence, and adaptability, is to teach concepts. Concepts are teamwide principles that allow players to recognize what’s happening on the ice and respond together. This isn’t about “wingers go here, D go there.” It’s about “the puck is in this zone, this is what we’re looking for, and this is how we respond.”

Hockey should be taught in such a way that every player, regardless of position, can understand and react to the game based on what’s in front of them. Systems are limiting; concepts are liberating. They allow for creativity, improvisation, and most importantly, adaptability.

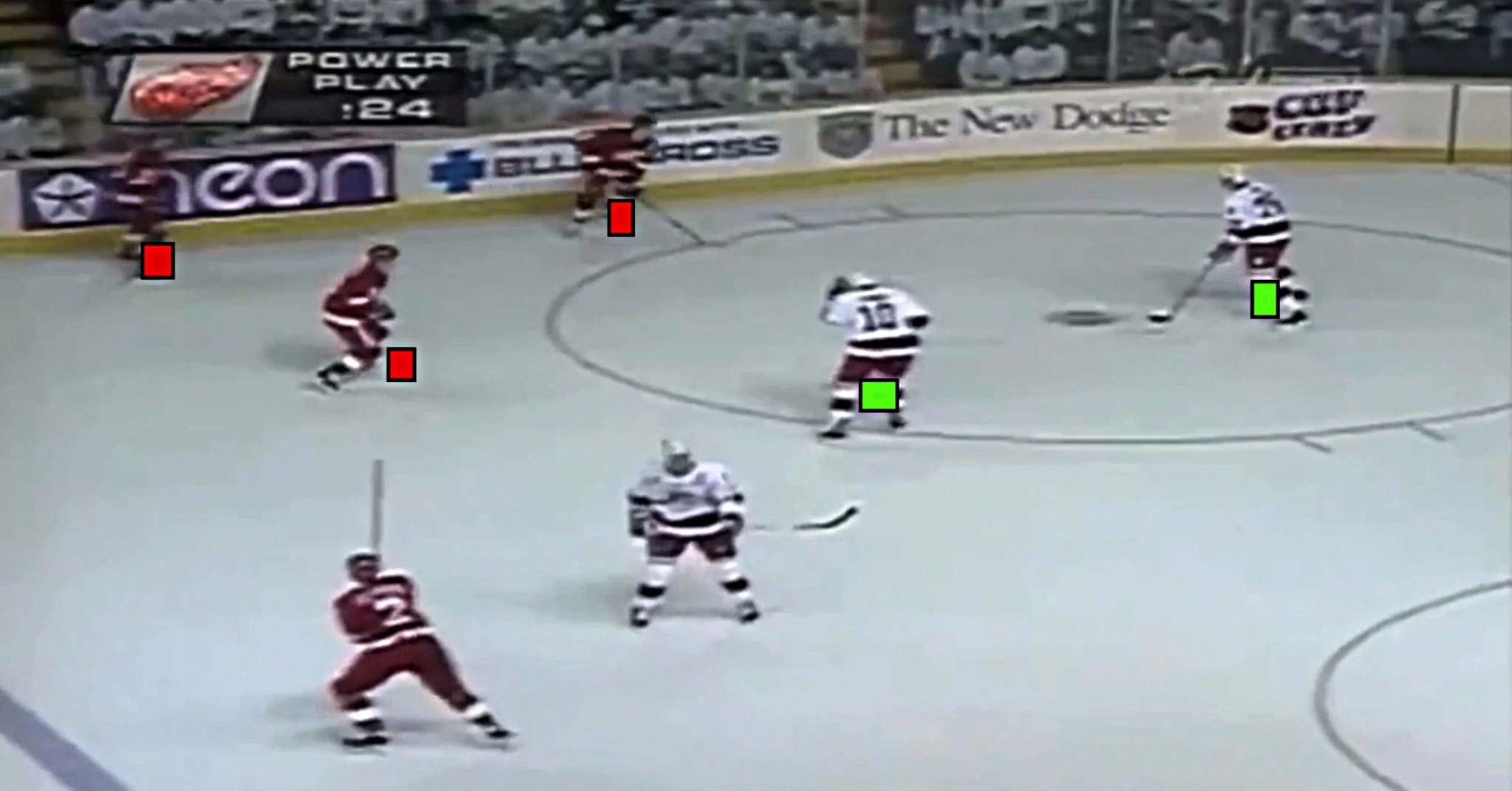

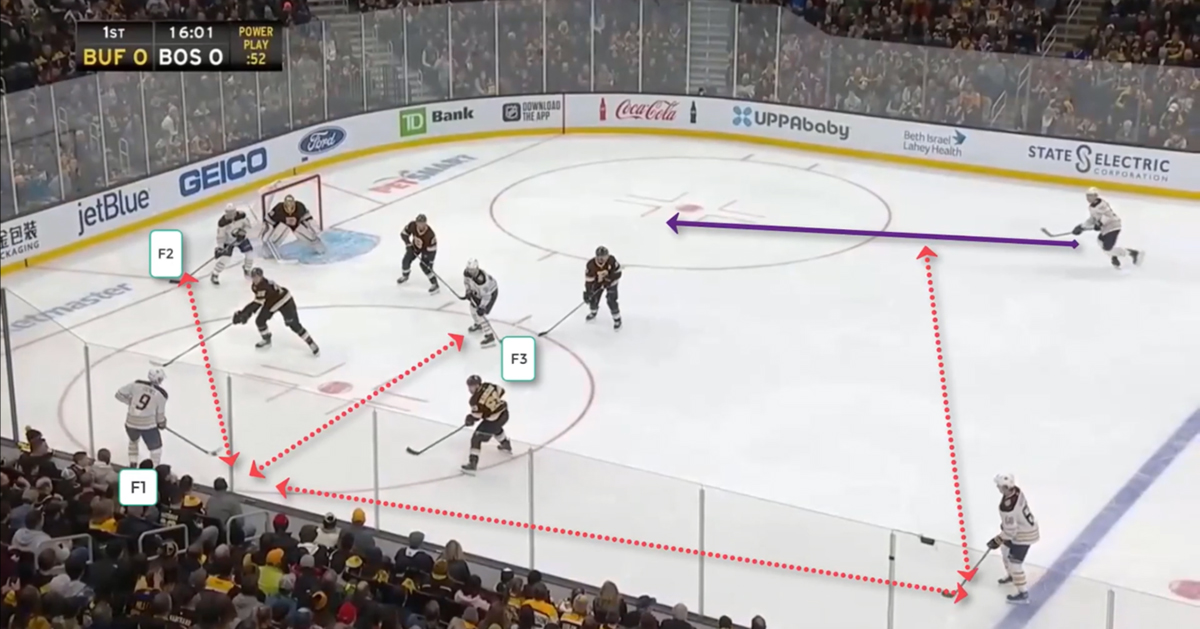

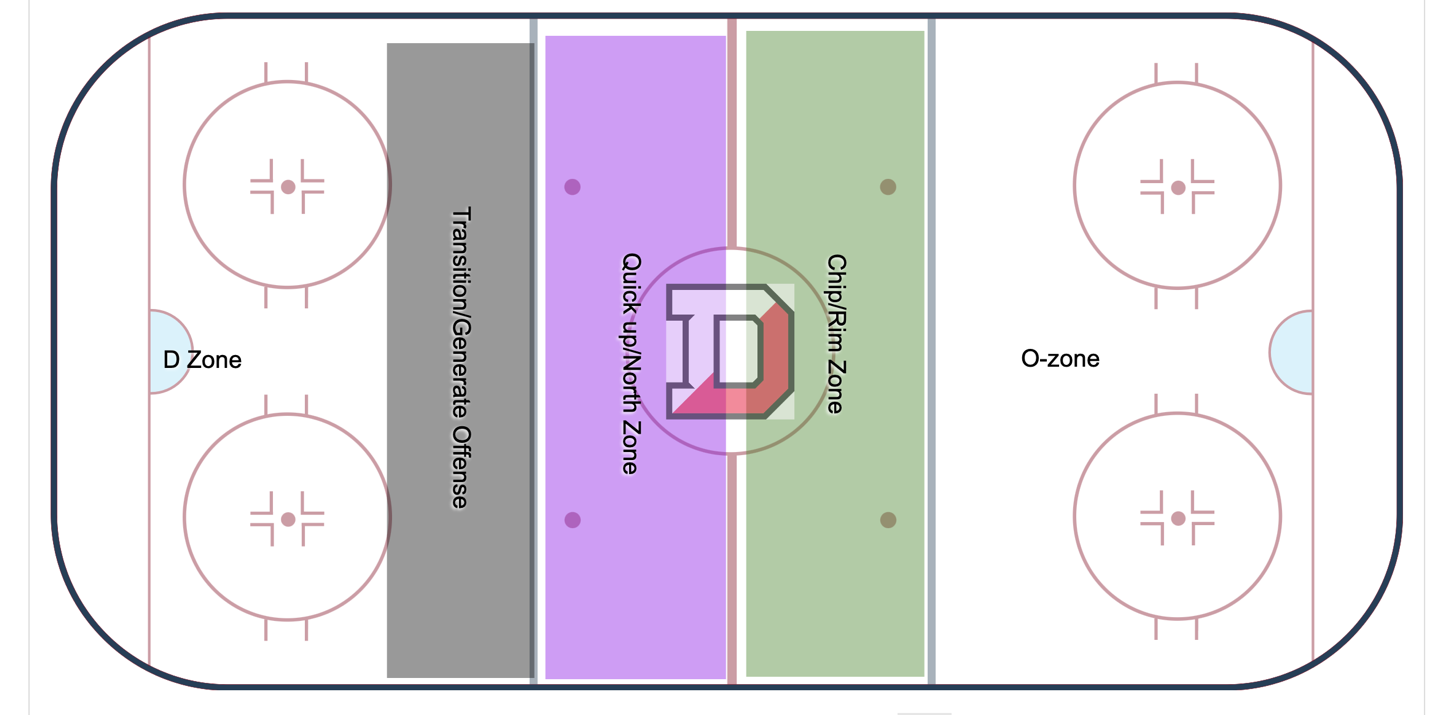

Teaching Through Ice Segmentation

One of the most effective ways to teach concepts is by breaking down the ice into segmented zones and attaching specific, teachable tactics to each. This method not only simplifies decision-making but gives players a map of predictable team behavior. It’s not a new concept, but one that holds enormous value.

Each zone: offensive corners, blue line entry space, neutral zone lanes, defensive net-front, etc., is taught as an area with predictable cues. The concept becomes: “If the puck is in this area, we operate under this principle.” For example:

- Offensive corner: Closest player pressures with inside-out angle; next player reads for retrieval or support; third player supports high, or pinches based on the F1 angle and D pinching.

- Neutral zone wide lane: If opponent puck carrier is stationary or support is limited, F1 can pressure aggressively while F2 reads the angle and F3 closes space in anticipation.

- Defensive zone low slot: All players understand their primary responsibility is net-front protection and sticks in lanes, regardless of position.

Segmenting the ice allows players to develop a zone-based reaction system that is teamwide and predictable. Each segment has its own conceptual logic, helping players build a mental framework for how to behave in high-speed scenarios.

The idea isn’t to overwhelm players with variables, contrarily, it’s to give them clarity through repetition: “If the puck is here, the concept teaches me to do this.”

Example of Segmented Zone (Segmented NZ)

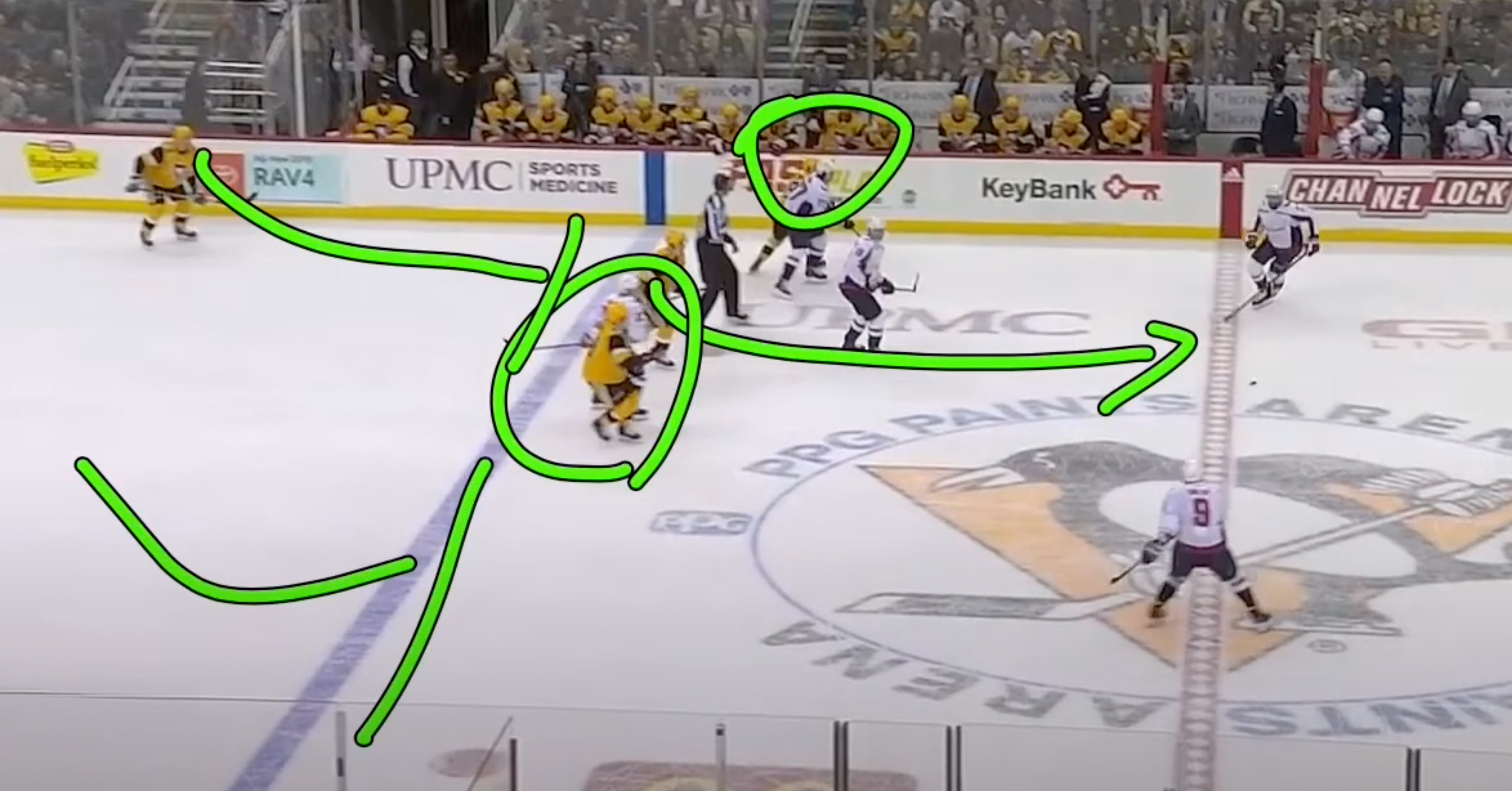

The Forecheck: An Example in Conceptual Teaching

Let’s apply this to one of the most misunderstood elements in hockey: the forecheck.

Rather than simply labeling a system “we play a 1-2-2” or “we run a 2-1-2”, we need to start with deeper questions that help players think critically:

- What are we trying to accomplish with the forecheck?

- When is the puck retrievable and when is it not?

- Who is the closest to the puck and what is their angle of approach?

- What should the rest of the team read off that first player’s action?

The answers to these questions create a team concept that players can understand regardless of what the scoreboard says or how the play develops. If F1 sees the opposing D bobble the puck, or the situations reads as winnable, the team has the green light to pursue aggressively. If F1 reads a clean breakout forming, the reaction may be to contain and delay instead. But this only works if the team has been taught how to read F1’s route, how to slide into pressure support or delay coverage, and how to rotate seamlessly without worrying about which player is a defenseman or a forward. Another beautiful point is that there is no wrong decision, every player reacts as one unit.

Teach Positionless Hockey (this should be word, by the way, positionless)

Conceptual teaching naturally leads to a more positionless style of play. Not in the sense that roles disappear entirely, but in that any player can make a play and take over a responsibility based on their proximity and angle to the puck. This builds flexibility and trust within the group.

It also opens the game offensively and defensively. Forwards should feel empowered to cover the point or drop low to break up a cycle. Defensemen should feel confident carrying the puck or driving the net off a rush. If the team understands the concepts, then players don’t need to ask permission to make a hockey play. They simply act, and the team reacts around them.

This is how trust and IQ are built. Players gain confidence from knowing their teammates will adapt if they jump in. Over time, this leads to a team that is not only more skilled and dynamic, but more resilient under pressure.

Reinforcing Through Repetition and Reaction

The shift from systems to concepts isn’t just theoretical. It has to be lived out on the ice. That means structuring practices around decision-making and reaction-based drills, not just pattern work.

Create drills that:

- Emphasize puck recovery in zones with multiple options.

- Train players to read support layers off a teammate’s angle of approach.

- Reward intelligent reads rather than rigid patterns.

- Mix player positions so everyone is expected to fill each role at some point.

Build small area games around segmented zones. Give each zone a principle. “In this box, we pursue if puck is bobbled; otherwise, we contain.” “In this area, closest player engages; everyone else reads off the direction of pressure.” These rules, when repeated, become instinct.

It’s not about giving players total freedom; it’s about giving them structured freedom. Within each zone, the team understands how to behave, how to adjust, and what outcomes they’re trying to create.

Teaching IQ and Confidence

Hockey IQ can be taught even to players who may not be naturally creative or instinctive. What they need is:

- A clear framework for decision-making based on puck location and pressure.

- Repetition in live scenarios where their choices lead to visible outcomes.

- Confidence in knowing that no matter what they do, their teammates will read and respond accordingly.

That’s the difference between a team of players running a system and a team that plays as one mind.

Coaches Must Lead the Way

All of this requires courage and vision from the coaching staff. You have to be willing to let go of system rigidity in favor of long-term growth. It means tolerating mistakes in the short run for the sake of teaching decision-making, knowing that success is born out of failure. It means resisting the urge to “just plug in the 1-2-2” when things go sideways.

More importantly, it means taking responsibility for developing smarter players, not just compliant ones.

It’s time to throw away the static playbook. Start teaching the game in layers of logic, not lines on a whiteboard. Teach zone-based reactions, read-and-react support, and the power of conceptual understanding.

Because at the end of the day, hockey isn’t about where you were told to go, it’s about understanding why you go there, when to go, and how the team moves with you.

That’s the game. And it’s one worth teaching the right way.