It’s easy to read this article and see hockey is the primary focus of the Okanagan Hockey Academy. You’d be wrong. One thing is emphasized more than anything: education.

Hockey Factories FREE E-book: A DEEP DIVE INTO THE WORLD’S TOP HOCKEY FACTORIES

***

Brett Calhoon starts every day like millions of North Americans.

He wakes up at 6:30 am at his home in Oliver, British Columbia, gets dressed, grabs breakfast, greets his family and heads out to catch a bus that will bring him to Penticton by 8:30 am to begin his work day.

He’ll put in a hard day’s work through a challenging practice in various activities throughout the day, hops back on the bus and heads home at 5:00 pm to have dinner with his family, finish up any extra work and gets a chance to unwind before getting up the next day and doing it again.

The difference between Brett and the many, many others that work the 9-to-5 is he’s not going to an office building or sitting in a boardroom.

Brett is going to Penticton High School from 8:30 am until 1:00 pm, and then he goes to the rink.

Brett is a student of the Okanagan Hockey Academy.

He’s a 5-foot-10, 16-year-old forward on the OHA’s U18 Prep team that plays in the Canadian Sport School Hockey League and was a 9th round pick of the Medicine Hat Tigers of the Western Hockey League.

Brett is a student-athlete.

His activities after class include getting on the ice for practice, getting in the gym, doing off ice training, watching and learning through video, meeting with his coaches and trying to make himself the best hockey player, student and person he can be.

For nearly 20 years, the Okanagan Hockey Academy has established itself in British Columbia, and now around the world, as a premiere destination for players like Brett who want more – on and off the ice – as they grow as people.

“I would have never got to where I am today without OHA,” Brett says adamantly. “They’ve helped me as a person, also. Some of the coaches, they have taught me lifelong lessons and it’s helped build my character, keep me humble and it’s really amazing.”

“All the coaches are NHL caliber, it makes a huge difference. Practicing every day, going to the gym every day, it’s a big step, but that’s what you need to get to the next level.”

Brett’s parents, Deb Sidwell and Alvie Calhoon, have seen the difference as well.

“His level of skating and strength and speed all improved on an ongoing basis, especially over Covid where we didn’t get to see him for almost a full season,” Alvie remarks. “He was doing decent at that time to now, really becoming a different player.”

The COVID-19 pandemic affected many players, many different ways. For Brett, he thought he lost a bit of exposure in the upcoming WHL draft because he wasn’t playing. But, unlike many others in that draft class, he was on the ice every day.

“We were still practicing, still playing intrasquad games, still training, all of that stuff,” Brett recalls. “Looking back, that was super beneficial when other players weren’t able to do anything, we were at it every day.”

“As his parents we were sitting back watching this kid with these dreams and goals saying ‘how do we get him there?’” Brett’s mom, Deb wonders. “The fact that OHA was able to keep up with the training and development meant everything because he was ready when he went out to Medicine Hat’s camp.”

As a 9th round pick, Brett was definitely not a shoo-in to get many looks on an experienced team.

Instead, he left there with a signed deal.

“When he was drafted, he wasn’t signed,” Deb mentions. “So, we went out there in August and if it wasn’t for OHA getting him prepared and trained over that year, I don’t know if he would have been signed because he was a lower pick.”

It was a lot of extra work, extra time and extra cost to get Brett to where he is today, but in exchange Deb gets something even more valuable. Something that sets OHA apart from the rest.

“As a family unit, he’s home every night,” Deb says with a smile. “It’s like a normal day now, he’s home at 5 o’clock and we get family time and to actually have a life with him.”

“We wouldn’t change it at all, we got to keep him home and I’ve got that top notch academy and I get to keep my boy home longer with me.”

***

Pamela Nordin would agree.

The wife and mother of two boys has felt the impact of juggling a hockey schedule, when hockey isn’t the primary focus.

“What we found here was the all-inclusive, structured program,” Nordin shares. “We are no longer driving our kid around all times of the day and getting him home to worry about homework and then your weekend games where we are going all over the BC Interior. It all kind of fell on the parent.”

Tough for any family, even harder with Pamela’s husband, who travels internationally, gone 3-to-5 months at a time.

“It became more and more daunting with Emmett’s hockey schedule to the point that I even went down to part time work for a while.”

Emmett Nordin (bottom, second from right) and his family knew about OHA and knew some people who had been involved at the school, so he got invited to a shadow day.

“He went to that day, and he came home with the biggest smile on his face,” Pamela recalls. “It was a big decision, but it was an easy decision because we had this academy in our backyard. When we learned how they managed the school and the sport, we knew he had every opportunity to succeed.”

And just like the Calhouns, the Nordins have reaped the benefits.

“I went back to full time work. I drop him off at their drop off spot and I pick him up for dinner and he’s at the kitchen table with all of us,” Pamela revels. “In the four years before him going to the academy, we might have sat at the dinner table together maybe twice a week. You can’t replace that.”

The Grassroots

The Okanagan Hockey Group has been running hockey camps in the area for over 50 years.

This community staple originally drew players from across BC & Alberta, but now The Okanagan Hockey Group has operated camps in Canada, United States, Mexico, Japan, Hong Kong, United Arab Emirates, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, England, Scotland and Denmark.

The group took their next step in 2002, launching the Okanagan Hockey Academy out of Penticton, BC.

It was the first hockey academy to be recognized by BC Hockey and Hockey Canada.

They started with one team, but over their time in BC, they grew to six boys teams and two girls.

They have since expanded past the BC border to launch similar academies in St. Pölten, Austria (2008), Swindon, UK (2012), Edmonton, Alberta (2015) and most recently in Whitby, Ontario (2018).

Before the expansion began, the hockey schools would draw current and former NHL players and coaches to help as instructors at the camp.

One of those instructors was Dixon Ward.

The Leduc, Alberta, native and 10-year NHL veteran hadn’t yet retired, but was asked by part owners Alan Kerr and Jeff Finlay to come to Kelowna and be a guest at the camp.

“The week ended and I said, ‘That was a fun week, thanks a lot,’ and Alan said ‘Wait, where you going?’” Ward recalls. “He said, ‘I need you for the next two weeks, I don’t have any more instructors.’ So, I got roped into three weeks of hockey camps and went back to Europe that fall and retired after that.”

What he thought was a fun week, has turned into much, much more.

“When I came home again, I got involved in talks with Alan and I joined up on the partnership side of things in a small way with the understanding I would be part of the Kelowna camp side and a little bit of assistant coaching part time with their Penticton hockey school,” Ward says. “That lasted about two weeks.”

“All of a sudden I was coaching a team and was right in the middle of all of it,” Ward laughs. “As it progressed over the next few years, I took on more roles with the organization – sales, marketing, hockey operations, running camps, recruiting and it was a really good introduction into the business as it was going through its biggest growth.”

After Kerr and Finlay left the company, Ward’s position continued to expand.

“(Current President) Andy Oakes and I really set our sights on the growth and development on the business side,” Ward explains. “That’s where we started expanding into Europe and Edmonton and Ontario. The last 7-8 years have been really strong for us.”

“Getting involved I didn’t know what the business model looked like, I just kind of fell into it and I really enjoyed the camps and getting involved with the kids and helping their development and I was hooked from there,” Ward admits. “Now I’m in so deep, there’s no getting out.”

It was a slow start for the Academy, namely because the traditional minor hockey associations weren’t receptive to playing against them.

“They were very standoffish about playing private programs,” Ward admits. “What we had to do was come up with our own format and our own competition and the only way to do that was to start the CSSHL – that’s when we really saw growth happening across Western Canada.”

In 2009, five schools came together to create the Canadian Sport School Hockey League. The CSSHL launched with five sport schools and eight teams over two divisions.

The league now boasts 26 accredited schools and 84 teams over six different divisions.

In the Preliminary Players to Watch List for the 2022 NHL Entry Draft, 29 CSSHL alumni have been selected.

“The consumer at that time started to demand choice and not to be pigeonholed into their local minor hockey associations,” Ward states. “We were always front and center saying having a choice for your child is something we have promoted from the start.”

As the league got established, the quality of players started to improve dramatically, and the school saw tremendous growth from some of the players who would play at this level and go on to junior hockey or NCAA.

The new wave of players came to the program as elite talent looking for professional coaching; they wanted more on and off ice training and a set schedule.

“The initial recruitment process was really the ability to combine all the key areas to youth development into one program – starting with the educational development in a highly structured environment,” Ward shares. “What was attractive to people initially was the combination of academics and athletics to create a consistent daily schedule.”

“We can utilize daytime ice and achieve the academic goals we’ve set out and be done by 5 pm every day so kids can have the proper nutrition, proper rest, proper time to complete homework and spend time with family instead of having practices and games all over the place at any given time.”

***

The Education Of Hockey

“Everything I have today, I owe to hockey.”

Mike Needham sits behind a desk during our Zoom interview, in front of a white board with names and strategies arranged around it.

He looks like a teacher.

In fact, in many ways, he is. And that connection is where his OHA story begins.

“I’ve always been involved in the game, I love hockey,” Needham regals. “I missed the competitive side and the teaching side and I did coach a bit while my son was playing in Penticton and I got the itch back and I thought this was a really good opportunity in a real quality environment where you can have a big impact on these players’ lives.”

Needham’s son came to the academy as a 15-year-old and played on the U18 team during his time.

At the time, Needham was transitioning out of his own business and got a chance to see the day-to-day of what his son was involved with, so he picked up the phone and talked to Dixon Ward and Andy Oakes to see if there was an opportunity.

Needham’s hockey background up to that point speaks for itself. As a member of the Kamloops Blazers, he amassed 243 points in 176 games, capping off his junior career with a Gold Medal at the World Junior Hockey Championships in Helsinki, Finland.

There he played with Eric Lindros, Patrice Brisebois, Stephan Fiset and Dave Chyzowski and against the likes of Pavel Bure, Jaromir Jagr, Robert Reichel and Bobby Holik.

Needham was drafted in the 6th round of the 1989 NHL Draft by Pittsburgh and would go on to play 81 games with the Penguins, winning a Stanley Cup with the team in 1992.

“I can’t tell you where it is,” Needham jokes when asked where he keeps his Stanley Cup ring. “I have a safe at home, I don’t wear it a whole lot because they are pretty big but I’m very proud of it. I’ll take it out for special occasions. Every year I’ll bring it in one day and show the kids I’m teaching that year.”

After his pro career, Needham returned to Kamloops as a skills coach and assistant coach, before becoming the full-time head coach of the U15 Prep Bantam team at OHA.

He’s been around some of the best coaches in Canadian hockey history, namely Don Hay and Ken Hitchcock.

He spoke about being a sponge around those two icons of the coaching profession, and how the game has changed from his time as well.

“When I first started coaching I remember playing for guys like Ken and Don,” Needham continues. “It wasn’t about them developing trust, they just told you what to do. You ran through the wall if they told you to. But that’s all changed.”

Needham had the all-important role of being one of the first points of contact for kids as they arrived and began their time at the Okanagan Hockey Academy.

That’s just how he wants it.

“The biggest thing I see with minor hockey kids that first enter our program is the lack of hockey sense and knowledge of the game,” Needham points out. “We have the ability to really change that and start thinking the game, understanding team concepts. They are all normally very skilled, but it’s the understanding of how to play.”

The message when they walk in the door is simple. One you will see referenced throughout this article.

“It’s the same every year. I want to teach them what it means to work and to compete on and off the ice,” Needham says. “What does it mean to work hard and give your best effort 100% of the time, every day? You have a group of like-minded kids with the same goals in mind that want to learn and it’s a great environment – similar to any junior or NCAA environment they get exposed to so much earlier.”

The day-to-day his son experienced is where Needham gets his motivation from. He is a hockey coach, but he’s also a guidance counselor, a mentor, a teacher and a friend.

“Being immersed in it daily, you develop relationships and trust with these kids so quickly because you’re always with them and always helping and working on getting better,” Needham states. “A big part of coaching now is that ongoing relationship beyond the game. I enjoy getting to know if they are golfers in the offseason, or if they like to fish. Building that trust is one of the best parts of this job.”

He’s been behind the bench and watched many players go through the program and on to successful hockey careers.

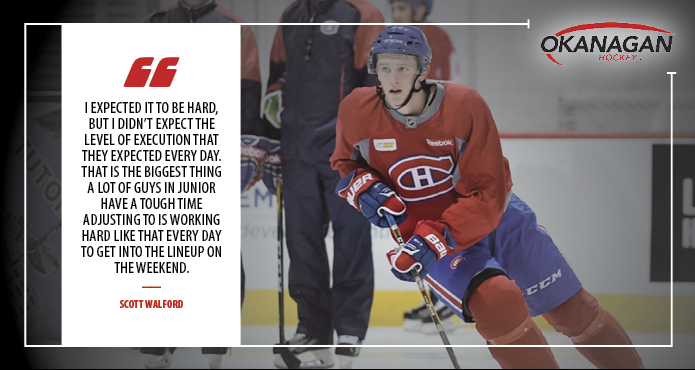

Scott Walford, a 3rd round pick by the Montreal Canadiens in the 2017 NHL Draft, credits Needham for making him the player he is today.

“He believed in us, he made us play at a fast pace,” Walford remembers. “He played in the NHL so he expected a certain standard of practice that hadn’t been expected of us before and that’s really why we had such great success under his leadership.”

“Mike taught me how to breakout pucks and how to get pucks through from the blueline,” Walford continues. “He ran a tough practice for defensemen but now that I look back, a lot of my game is my first pass and I can extend that back to learning from him – putting pucks up the wall, making a good break out pass and it would always end with a shot from the blue line – so he really helped me a lot with that.”

Walford is currently in a joint honours program for economics and accounting at McGill University.

He rode the bus too, from Kelowna to Penticton, when he enrolled at Okanagan Hockey Academy during his Bantam year.

“The biggest adjustment for me was what was expected day in and day out,” Walford explains. “It’s easy to be good at 2-3 practices a week, but when you are practicing five times a week and working out five times a week, taking the bus in every day, going to school, going to the rink and taking care of everything after that, it really shows you how to be a pro.”

***

“It was an easy decision – the pedigree they had, the program and the plan they had set up, it was a good place to be.”

With the start of the 2021-22 NHL season, one young player being counted on to continue his development within the Detroit Red Wings organization is Michael Rasmussen.

Teams in a rebuild need to hit on their 1st round picks. Rasmussen went 9th overall to Detroit in 2017.

In his U15 Prep year, Rasmussen put up 87 points and 123 penalty minutes in 59 games.

He was special the day he walked in the door.

“The kids that come in here are very driven, they have an internal drive where you have to ask them to give that effort,” Needham says. “Michael just wanted more. He wanted to be on the ice more, and we are on the ice every day. He was competitive in the classroom, in the gym and on the ice.”

Rasmussen graduated from OHA to the Tri-City Americans, where he scored 157 points in 161 WHL games before beginning his ascent through the Red Wings’ organization.

“With Michael, you just had to steer him in the right direction. I would say, ‘you’re a Western League hockey player, you should go that route, here are things you can work on, but don’t deviate from the path you are on,’” Needham told him. “It’s relatively easy when they are so driven and internally motivated, it’s easy to coach them.”

“Malcolm Cameron, Mike Needham, Dixon Ward – I give them a lot of credit for where I am today,” Rasmussen admits. “They instilled in me the work ethic and drive to get better.”

Penticton High School

It’s easy to read this article and see hockey is the primary focus of the Okanagan Hockey Academy.

You’d be wrong.

Throughout my interviews, every “hockey” person I spoke to emphasized one important thing about OHA more than anything else – the education.

These student-athletes are just that. And at OHA, the classroom is king.

OHA’s Academic Advisor, Dave Nackoney, is one of the elder statesmen of the Academy program, having been on staff since 2003.

Nackoney by trade is a teacher, a counsellor and, at one time, a hell of a basketball player.

Studying at Brandon University, Nackoney won two Canadian Championships on the court and was also named an All-Canadian.

It wasn’t until he met the Academy’s original owner, Larry Lund, that Nackoney started to turn his focus to the rink.

“At any time in life you get to learn something new, I didn’t play hockey at all, but I was helping Larry’s daughter get into university,” Nackoney recalls. “Working with her created this relationship and he proposed I get involved with OHA. Through the process it’s been really exciting learning a sport like hockey when you come from a basketball background.”

The running joke that seems to be created is that Nackoney has the most power of anyone at OHA.

His say can keep a star player off the ice heading into a big tournament.

He’s also the one who can start a spree of high fives and encouragement from many different departments.

“Coach knows, parents know, study hall teachers know, so if a kid is doing well he’s getting five pats on the back by the end of the day, but if he’s not, he’s probably going to get the opposite.”

“Dave is simply amazing. I am so completely thankful and grateful for him,” Pamela Nordin speaks of her and her son’s time at the school. “He takes ownership over these kids and puts everything in place for them to succeed – there’s no reason they can’t. They have every tool within their reach.”

“We are student athletes and we believe in it – it’s a great relationship we have with Dave and the school and I have the ability as the coach to take things away from a kid that isn’t doing the work in school and I think that’s important,” Needham remarks. “I’ve left kids back from big tournaments because they were behind in school and it’s hurt our team, but it sent a message to that player that I think was long lasting to them – you do your work, or there is going to be consequences.”

“What we do here and our goal here every day is to create an environment that allows young people to develop in the key areas they want to improve in – hockey, school and character,” Ward points out. “The academic success our kids have is fantastic. The vast majority of kids will improve their academic standings with our program compared to not with the program.”

“By far, our strongest pillar and connectivity and what we do as a program is how it connects to our academic expectations,” agrees OHA General Manager Scott May. “Hopefully, we are a leader in the industry of education-based hockey and we have an impact on their son or daughter’s life that they are leaving here as better people, so they are able to be doctors, lawyers, engineers or hockey players.”

When the Academy got off the ground, the big part for Nackoney and the rest of the staff at Penticton High was to amalgamate the school and the players coming in.

The entire school timetable was changed, so it would work for all the players and teams that were now affiliated.

Nackoney even mentions looking at different types of sports-based academies – like skiing – to find out what worked best for them.

But Penticton High is not just a hockey school. The success of the hockey program can now be felt in many other corners of the institution.

“The swim academy took the same path and now we’ve won four straight provincial titles, we have five national team swimmers because they have proper times to do their studies, time for their craft and time to rest,” Nackoney tells us. “You develop one culture and you get people who are used to excellence and it gets contagious.”

“The best thing that works for us is that we are one big team. There is a real professional attitude amongst their staff,” Nackoney says. “I couldn’t have more respect for the people over there, and the same for the teachers who work at the school.”

***

Having the best coaches, the best teachers and the best education platform is one thing.

It feeds the mind, the skillset and the drive.

Heather Perrin takes care of the rest.

The OHA’s Manager of Athletic Therapy & Medical Services has worked in a number of sports, including rugby, judo and lacrosse.

But for her, the best chance to land a full time job doing what she loves was in hockey.

“There’s not that many full time jobs in hockey, especially for females,” Perrin admits. “When I returned to BC, coming in and working in an environment with multiple coaches and multiple teams with multiple age groups forces you to be a dynamic person and I loved the idea of that.”

Perrin joined the school in 2014 and her job, day in and day out, is to make sure the boys and girls at this academy understand how to use their bodies to their advantage – and how to care for them properly.

Perrin has been to the top of the mountain.

In 2018, she had the opportunity to take a year sabbatical from OHA to work with the Canadian National Women’s Hockey Team, serving as the team’s therapist for the Olympic Team that captured silver in South Korea.

“It’s a once in a lifetime thing. I’ve never worked so hard in my life and never felt so proud and humbled to represent Canada,” Perrin beams. “It was something I have worked my whole life for and was a pretty incredible moment.”

I asked Perrin if it’s a challenge getting kids into the gym, training their bodies, and beginning those routines, somewhat expecting the answer to be yes.

Perrin just chuckled.

“At the start, it’s more about toning that down and channeling the excitement,” Perrin comments. “When they walk into the weight room, they just want to bicep curl and bench press. It’s hard because we don’t actually let them do that too often at the start because we have to educate on proper weight selection and how important the movement is instead of who can lift the most.”

It’s also just as much about understanding their bodies.

“First year kids in the academy don’t know that feeling of their whole body hurting. There’s a lot of education around hurt versus harmed,” Perrin continues. “Yes, you’re hurting today and that’s ok. This pain is ok. Yes, your rib cage is bruised, your back is bruised, all of that does not mean you are injured and can’t play – this is your new normal.”

Another tool she regularly gets to use to her advantage is one she preaches often in our conversation: using other sports to develop skills that can be a benefit in other ways.

“I think the fact that in the offseason, when hockey is done, we play soccer, we play ultimate frisbee, and that makes a big difference early on,” Perrin says. “You learn how to move to space, you learn how to cut, how to lose your opponent and early on they don’t realize how much that translates to hockey.”

Hockey Is The Vehicle

As the program has grown and evolved, another key piece was brought into the mix very recently.

Scott May was running a similar program at the Delta Hockey Academy as the Director of Hockey Operations since 2013.

There he helped Ian Gallagher, father of Montreal Canadiens’ forward Brendan Gallagher, grow that Academy from two teams to eight.

He also coached the Midget Prep team and was the Head Coach of the Female Prep team in the 2018-19 season.

Prior to his coaching career, May spent four years at Ohio State University, before being drafted by the Toronto Maple Leafs in the 7th round of the 2002 NHL draft.

He played eight seasons of professional hockey in the AHL, ECHL, Germany and Italy.

In 2019, May was looking for a new challenge. He saw the OHA and the people around it as an opportunity.

“Getting the chance to learn from Dixon Ward and Andy Oakes, for me, to have mentors like that to learn the business side of it was driving and motivating.” May admits. “I was able to move off the bench as a coach to more of a business manager and GM, which was a challenge I was really looking for.”

Instead of running a bench of players, May now has a staff of 16-20, constantly looking to make the hockey program bigger and better.

But that’s not just in wins and losses.

“At the end of day, hopefully we see success on the scoreboard, but this is truly about the growth of the young men and women that run through our program,” May says. “Hockey is the vehicle that gets them there, once every blue moon we’ll have an NHL prospect come through, but what I think we do really well is the humanistic part, the community service part, the academic part.”

May says there isn’t necessarily a blueprint for what kind of kid will have success at OHA, but there are definitely characteristics the school looks for when drawing up their next recruiting class.

“They have to have a minimum ability but see potential – does the kid eat, sleep and breathe hockey,” May starts. “You have to have passionate kids who want to be here. Character is a huge component of what we do. Trust, honesty, and hard work; that has to be the pillars we have to stand on. It’s a huge time investment, it’s a huge financial investment so we must make sure we have the right people in here that are going to have success in the long term.”

“We have to be the Cadillac of programs as far as what we provide,” May contests. “I think we check all the boxes when it comes to the academic expectations for what we do here and spend a lot of time, effort and resources to make sure that is a staple we believe in.”

When May joined the program, the recruiting class was already set, but as he explains, success is always lagged in this process.

“I tried to look at this as a three year transitional plan,” May says. “Year One – assess and evaluate, Year Two – implement change, and year Three – reassess and evaluate the changes you’ve made and build off platform for longer term vision.”

As for the on-ice product, with so many age groups and so many teams, thus so many coaches under one umbrella, collaboration is the key.

“There is flexibility on each team and that’s the fun of coaching. The fundamental basis of what you’re coaching is the same across the board,” May instructs. “There is a progression plan and building blocks of starting with the basics with our U15 team all the way to our U18 teams. It’s a constant teaching and repetition of the structure and the habit and the routine of the skillset and the information we are giving them.”

“We like to think we have a template that each coach will follow – if you come and watch an OHA team play, you’ll get a consistent feel from our U15 team all the way to our U18 team,” Needham concurs.

“The more you do that people start talking the same language and I think that’s an important part for us as staff that the message is clear, direct and we are using the same language,” May continues. “If the kids don’t get it, it is not their fault, that is 100% on the coach. That’s the business of making them better and that shows our coaches they have to explain it differently, we have to change our scripting.”

“We are solution-based programming where we have to find answers to our problems, not just identify problems.”

Ward sets out every year with a list of objectives he wants accomplished by his coaches and it’s something they document weekly.

“We want to move better, play faster, handle the puck better, score more, work harder, be better people and understand the game better,” Ward explains. “If one coach in Ontario has a great model for teaching one part of the game, we can share that with the other coaches and they say ‘yeah, I’m going to try that too.’”

“Standardizing our philosophical approach to how we want to play, without taking away the individualism of each coach’s ability to run a different team play system as they go, is a big part of what we are doing.”

Sometimes It’s What You Don’t Say

In our first conversation, Ward makes a profound statement.

“Sometimes it’s more important what we don’t say than what we do say.”

What does that mean, exactly?

“We are not here to create NHL hockey players, we are trying to give kids the opportunity to develop and to give themselves a chance to move to the next level of development,” Ward says. “We are not going to jeopardize our integrity because we need your kid to score three goals in a bantam hockey game, that is not something that is important to us.”

“I want to make sure that people see they are cared about, there is a vested interest in every student here, every son and daughter, and I hold that very close to what my deliverables are,” May recites. “100% it’s about the people. We are teachers at heart and we absolutely love what we are doing. There is such a passion and a drive for it. End of the day it’s sharing that environment with those kids in a fun, structured, healthy and long lasting success in life.”

“Understanding how the real world is going to treat you,” Needham notes, is one of the most important lessons he tries to teach. “I’m a very straight forward coach. I don’t sugar coat. I’m honest and I think to a man they appreciated that and they’ll come back now and say ‘now I get it.’ In the real world, if you don’t do your job, you don’t keep it and if you don’t do it well, you’re going to hear about it.”

The values of the program are something Ward reiterates throughout our talk.

“They are all important things, but they only work if you work hard, you’re honest, you’re respectful and you understand you are going to fail most days and you’re ok with failure, because that failure will help you succeed,” Ward cautions. “How you act when you succeed is just as important as how you act if you fail.”

The OHA Experience

Every hockey player, coach or parent that’s rode the bus, knows the bus.

It’s where lifelong friendships are made and victories are celebrated. It’s the happiest place in the world after a win, and the darkest, quietest corner when you don’t.

For guys like Brett Calhoon, Scott Walford and Michael Rasmussen – the bus was just the beginning.

“The friendships, first of all, some of the people I’ve played with are going to be my brothers for life. Even the coaches, I text some of the coaches on a daily basis and it’s just a big family,” Calhoon boasts.

“Everyone makes going to the rink, going to school just a good experience,” Rasmussen reflects after he steps off the Little Caesars Arena ice surface from practice. “To this day, the peole are some of my best friends and people I’m always in contact with so above anything else it’s the people who run that place.”

“A lot of my memories are stuff on the ice like winning championships, but a lot of them go back to the time with my billet family and the time with our players on the bus,” Walford shares. “We had a really special group of guys and I hope we can do a reunion some time because life gets busy but when you see them 5-10 years later, the connections never left. It’s the kind of brotherhood you don’t get much in life.”

As the next group of OHA students have begun flooding their campuses around the world, hockey may be the vehicle, but it’s people like Dixon Ward, Scott May, Mike Neeham, Dave Nackoney and Heather Perrin that are behind the wheel.

“I can only promise you one thing,” Ward states. “We are going to create an environment for each kid that is going to give them the best opportunity to succeed.”