Hockey in the prairies is a way of life. That’s all there is to it.

“It’s not an easy place to be because of the weather and the environment,” Delaney Collins remembers. “But in some ways, it is the easiest because you are not distracted and you’re so driven by everyone around you.”

“It doesn’t matter the weather,” Del Pedrick follows. “If it’s minus 35 degrees Celsius and the wind is blowing at 45km/h and you can’t see across the street, kids put on their toque and mitts and walk to the school or the rink. It doesn’t matter to them. It really builds some character.”

Respectfully, it’s a blip on the map.

Admittingly, coaches and former players will talk about how they had families drive right past the town without even knowing it.

“We’d get a call from parents that were almost in Moose Jaw, asking where the heck we were.,” Pedrick laughs.

To peek inside the campus of 400 students strong, central to a town with a population of around 260, is to see a college oozing with the tradition and pride of massive American universities.

Athol Murray College of Notre Dame was built in 1920, in the middle of the depression, by a priest who is referred to by those I spoke with as a renegade, a maverick and the most beautiful man they had ever met.

With three pillars holding the school strong – athletics, academics and spirituality – Athol Murray set into motion a facility and program that will stand the test of time and one that each person you’ll hear from speaks with such great reverence towards.

Tucked inside Wilcox, Saskatchewan, sits a hockey hotbed that bursts at the seams with character, that lives with the mantra of its founder that there is nothing better than working with youth.

Very few places you come across carry their school team name as an adjective used to describe yourself.

But walk through the halls of Notre Dame and you are a Hound for life.

================================

Delaney Collins is as decorated a Canadian hockey player as you will find.

Appearing in five World Championships with the national team, Collins has three goal medals and two silvers. Three times in those World Championships she has led the tournament in either most goals or most assists for a defenseman.

Her story starts in Notre Dame well before her first day of school.

“My dad was a teacher at Notre Dame; he was just inducted into the Manitoba hockey hall of fame – Rod Collins,” she beams as she shares. “There was a source of pride to be handed down my brother’s red gloves and hockey pants and it was just a matter of time until they fit, and I could use them.”

Collins started at the school in 1992, before then admitting to counting down the days from Grade 6 on until the time she would be able to call herself a Hound.

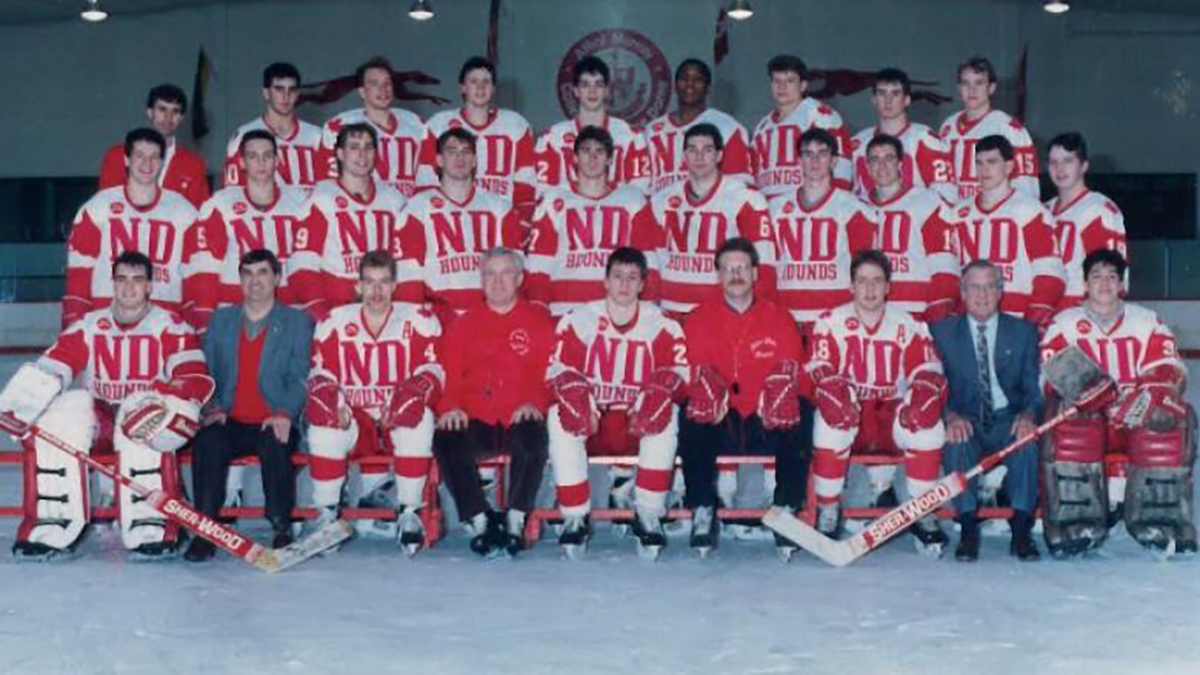

“The tradition, I feel like everyone will talk about that. The tradition is second to none,” Collins emphasize. “The red equipment, the red jersey, the rink and I feel like so much grows out of this tiny little community in the middle of nowhere Saskatchewan, there’s so much hockey and religion and academics.”

Collins, like many, discusses how easy it was to focus on those aspects while you were there. Without the joys of Wi-Fi and Playstations and streaming services, you lived and breathed the school, hockey and the environment.

“I remember going to college and people telling me about this famous tv show called Friends and I had never heard of it before,” Collins laughs. “When you get there, you become consumed by the excellence.”

That was the environment Athol Murray set out to create.

Stephane Gauvin attended Notre Dame, played on the 1988 Canadian Championship team and has returned to the school this year to serve as its principal.

He speaks so highly of the ideals and philosophies of Father Murray and the rich, historical history of the campus.

A campus that holds a true landmark at the centre, a symbol and focal point of the facility – the Tower of God.

“Father Murray was a Catholic priest, but he didn’t care what you believed in, as long as you believed in something bigger than yourself,” Gauvin tells. “He built the Tower of God in 1961. He wanted it built in Jerusalem as a bridge for those of the Muslim faith, Jewish faith and Christian faith. He spoke with world leaders, the pope, all of these people to do this and the prototype was built in Wilcox as a symbol that we can come from different places and different views but still get along. That’s what permeates this place.”

That tradition is as relevant today as it was when the Tower was first built.

Athol Murray, as if strolling the campus in the present day, is recognized not just in the building, but in its people.

“If you read anything about Athol Murray at all, at the heart of his plan for the school was helping the students reach their full potential,” says Eric Lockwood, who worked at the school for 30+ years. “Becoming a whole person, he would call it. The mind, body and spirit.”

“In this day and age, it’s hard to keep those things connected and as a program you may want to change but what has never changed was Athol Murray and his passion for athletics and academics,” Collins admits. “I feel like he was a bit different and slightly a bit of a rebel as a priest, but his tradition resonates with a lot of people and not just hockey players.”

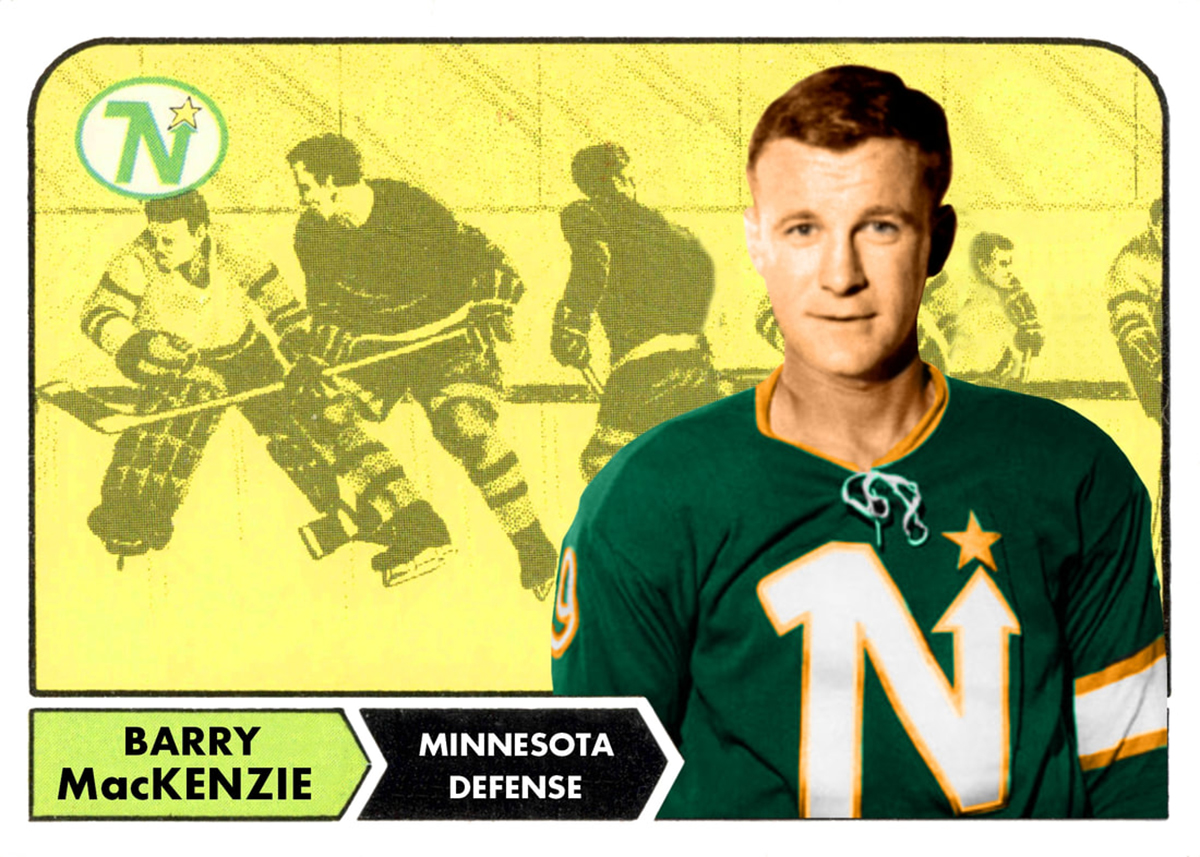

Two main characters of this story, and legends in their own right; Barry MacKenzie and Terry O’Malley met with and were around Father Murray to see his true wisdom.

“Athol Murray met his times, he met the Depression, but he found his gift and he did it,” O’Malley recalls. “He was a maverick, I mean, he’s the only one who could have done it, he was so stubborn and enthusiastic. He’s really a Canadian hero.”

MacKenzie agrees and shares a story of going down to Notre Dame before coaching at the school and having a chance to meet Father Murray.

“We met in his office for several hours, he toured us around the school and treated us like super stars,” MacKenzie continues. “When we got in the car after, my wife was crying. I asked her what was wrong, and she just smiled and said she had never met a more beautiful person in her life.”

The mind, body and spirit. The character development. The whole person.

That is what Father Athol Murray stood for, the principals he built his campus on and what is still felt by every student, coach and teacher that enters its lore.

================================

Getting a list of alumni was easy to sort through as we planned out this article.

It became very evident as I scrolled through the names, history and titles of these distinguished figures that a common theme had emerged.

There were a lot of coaches that have come out of this program.

You see it on the greatest stage of them all, guys like Jon Cooper, Barry Trotz and Rod Brind’Amour spent time at Notre Dame. Delaney Collins is now coaching with the Hungarian National Team and the Nashville Jr Predators after Mercyhurst University, Del Pedrick is an assistant coach with the Brandon Wheat Kings in the WHL and IIHF Hall of Famers, Barry MacKenzie and Terry O’Malley, began their illustrious careers at the campus.

I can assure you, that is no coincidence.

“It’s amazing when you think about the coaches that have come through that school,” Brind’Amour confirms my thinking. “Barry Trotz and Jon Cooper are two of the best guys who have done the job. They would all say the same thing, Notre Dame had a huge impact on them.”

Going to school at Notre Dame and being part of the ’88 Championship team, Brind’Amour can recount any number of ways the school has helped mould him into the person and coach that he is.

“You had to go through tough times, you had to fend for yourself, you had to mature, and they gave you the tools to do it but you had to learn how to handle the ups and downs of life and it prepared you for a lot,” Brind’Amour believes. “The discipline and the routine, it was huge for me. That’s what I learned there and that’s what I still use to this day.”

Pedrick came to Notre Dame in the 2007 season and revels in his time there as a young coach.

“No better place to raise a family than Wilcox with a bunch of good people around you,” Pedrick states. “Sometimes you’re responsible for 30-40 kids in the dorms and then a few others come over at 7:00 pm for math homework and your wife is cooking dinner for them and they are playing with your dog because they miss their dog at home. It gives them great insight and allows you to build that trust because they see your efforts in a holistic development sense and that you aren’t just interested in them as a hockey player.”

He left after the 2017 season, only to return as the U18 head coach in the 2021-22 year and drawing from his previous experience at the school to be able to focus on that team and collaborating with the other coaches in the program.

“I used to really enjoy jumping on the ice with other teams and learning from them, seeing how they communicate with players,” Pedrick says, talking about his second time around with the school. “There are not many original ideas in this game, but some coaches have the ability to make them better or worse. Going in with an inquisitive mind and getting to work with different coaches who have seen different things, definitely makes you a better coach.”

As Pedrick mentions, the setting gives coaches the opportunity to really invest in their players, not just athletically, but academically.

His philosophy, he admits, is not something all parents would be looking to hear, but something he says he has brought with him since his time at Notre Dame.

“You’ve never came across a sloth in the classroom that works his tail off on the ice – it doesn’t go hand in hand. I would ask parents about how school was going and have been told that wasn’t my concern. So, when you get a chance to help kids both on and off the ice, it gives you a lot of pride and lets you be part of something bigger than yourself – and that’s what Notre Dame stands for.”

Terry O’Malley has always been surrounded with great coaches.

It helped him become one.

“My first coach was Father David Bauer as a bantam,” O’Malley recalls. “He taught me so much right from the start. Even before then I had Roger Neilson. They were both humanists and had such a great influence on me, which is why I fell in love with coaching and teaching.”

O’Malley represented Canada at the Olympic and National team level, serving as captain of Team Canada at the Winter Olympics in 1968 where Canada earned a bronze.

He was inducted into the International Ice Hockey Federation Hall of Fame in 1998.

When I asked him about the honour, he quickly shifts attention to being given the Mother Theresa Award from Notre Dame.

“I was there 23 years. It was just a fantastic place to be,” O’Malley says. “We had an advantage when we were there because a lot of us had played pretty good hockey under some great coaches. Learning the fundamentals from Roger and Father Bauer, I always tried to replicate them, but you realize eventually you have to be yourself.”

His guidance on coaching today is as relevant and important as when he would have heard those messages as a bantam player.

“It’s trial and error getting players into the right situations most times,” he discusses. “The most important thing while you are doing that is talking to the players, letting them know what you are thinking, why they are playing where they are and moving players around to try to find that connection. It’s an involved process, it takes effort and if you ignore it, it will come back to bite you.”

Just as his pride for the Mother Theresa Award equals the honour of the IIHF Hall of Fame, same can be said for the way he talks about the academic success of his players compared to their on-ice accomplishments.

“We’ve had a lot of good hockey players come through the school and play pro and some play in the NHL but we have had hundreds go on to university on a scholarship,” he quickly adds. “We have a wall there, the wall of fame, and it shows all players who have played hockey but then we have all the players who went to university of scholarship. They get the same admiration from the other students and staff who are there now.”

It’s hard to have a conversation about Terry O’Malley and not have Barry MacKenzie’s name come up.

In fact, while talking to Barry, he got a call from Terry.

“We played on a bantam team together and we’ve known each other for all those years since,” MacKenzie reflects. “We went to St. Mikes together, UBC together, National teams together, Notre Dame together. We are best of buddies and have nothing but fond memories of each other.”

The two are cut from the same coaching cloth, though speaking with players it is also clear that MacKenize had the heavier of the hands.

“He was a master at understanding who was ready to go. He could read that so well. We were not fearful of him but so highly respectful of him,” Gauvin shares talking about the 1988 Championship team. “We were playing North Battleford one night and we whipped them something like 7-2 and he walked into the room after and said to us ‘you guys really pissed me off, keep your gear on” and he skated us for an hour after the game. It had nothing to do with the result it had to do with the engagement and character. But he was right. He saw something and he wasn’t wrong. We would all go through a wall for that guy and still would to this day.”

Eric Lockwood follows suit with his praise.

“Barry was, without a doubt, the best boss I could have had. He was demanding, he held you accountable, but he treated you like an adult.”

Rod Brind’Amour takes his admiration and respect a step further.

“I think of coaches and people who influenced me, there’s him and then there is everyone else way behind. I think he’s the best hockey coach ever. I had three years with him, so I was very, very fortunate.”

I shared the North Battleford story with MacKenzie to see if it jogged his memory.

The wry, immediate smile told it all.

“I always believed you could learn something, even if you’re winning 7-2,” he notes. “I remember telling them later in that game that I wanted to try a new system. So, I explained what I wanted to see but I kept telling them ‘You’re not listening’ and I told them that maybe 10 times. I didn’t talk to them about it the rest of the game but then I kept them on the ice and reminded them, you can always learn something. I know they tell that story.”

MacKenzenie closed with a story about his time in the NHL, although brief.

He played 6 games in the NHL with the Minnesota North Stars in 1968-69 and had been getting good reviews from in the media and his coaches. His family, however, was in Memphis and he was worried being away from them for so long.

He brought the concerns up to a manager and was promptly sent down, being told he’d never play another game in the NHL – and he didn’t.

“That was the best thing that happened to me,” MacKenzie says surprisingly. “Because of that meeting with that manager, it led me to the path towards Notre Dame, where my life was so much more impactful than if I had played pro hockey for another 10 years.”

================================

There is a sense of pride that is arguably missing when you compare Canadian universities and colleges to their counterparts in the United States.

If you attended the University of Michigan, you are a Wolverine. If you attended the University of Florida, you are a Gator.

It defines you.

Through our Hockey Factories journey, this has never been more evident than speaking with graduates of Notre Dame.

They are Hounds.

“I was just in Hungary, and we were at the Four Nations Cup in Budapest and one of the assistant coaches for Team Japan is a Notre Dame Hound,” Collins boasts. “The referee missed an icing and I look over and there’s an old Hound and we are laughing and did some reminiscing afterwards. It’s a small world, it’s a wonderful tradition. The more I played on Team Canada, the more Hounds I would come across.”

Very recently before we had our conversation, Collins’ father, Rod, had his induction ceremony and she talked about how much her phone was blowing up from former Hounds telling stories about him and their time at the school.

“Every single rink, everywhere in the world, I’m running into Notre Dame Hounds. They are everywhere,” she chuckles. “It’s its own brand, we understand each other. Being in Wilcox in the winter, you get a bond. You have to be there to know what it’s like. We all have that in common and it’s pretty cool.”

“It’s often imitated, never duplicated,” Pedrick feels. “Just the comradery in that town. The red and white nights at the rink where everyone gets dressed up and they lose a bit of their self consciousness, they are chanting and cheering, and the cross support there, you were taken in as family – you were a Hound for life.”

Some of the great stories don’t surround winning and losing, it’s the time on campus but also the support that comes from the surrounding town.

“They always say it takes a village to raise a child and that village is the definition of that.” Pedrick remarks. “It’s a caring community. It’s a simple way of life. Everyone is in everybody’s business but there’s a care factor there too. There are vested people in that school and that community.”

I asked several people I spoke with to describe Wilcox, Saskatchewan, to an outsider.

For most, it was hard to put into words. Like Collins said earlier: you have to be there to see what it’s like.

“Coming from an urban centre, you would realize how isolated it is, but it doesn’t take long to get that community feel,” Gauvin describes it best. “We have beautiful blue skies most days but we get that Saskatchewan wind. If you want to leave, you’ve got to walk 50km to Regina, you can’t just get out of here.”

This is something every person stated as a clear advantage for Notre Dame.

“When I got there, there was no internet, there were no phones – there was one pay phone at the end of the hallway for 60 kids,” Lockwood remembers. “Wilcox is a little bit of an island out there, still even with all the technology. I still think the biggest thing the school can offer is the social development. They come from their homes, to a degree they have to fend for themselves and on top of that, they had to learn to get along with three roommates. Sometimes it’s a kid from a rural town, a kid from Toronto and another from Paris or something, where English isn’t their first language. I think it was one of the best things we could do for those kids.”

However, the other great stories, as you’d expect, happen on the ice.

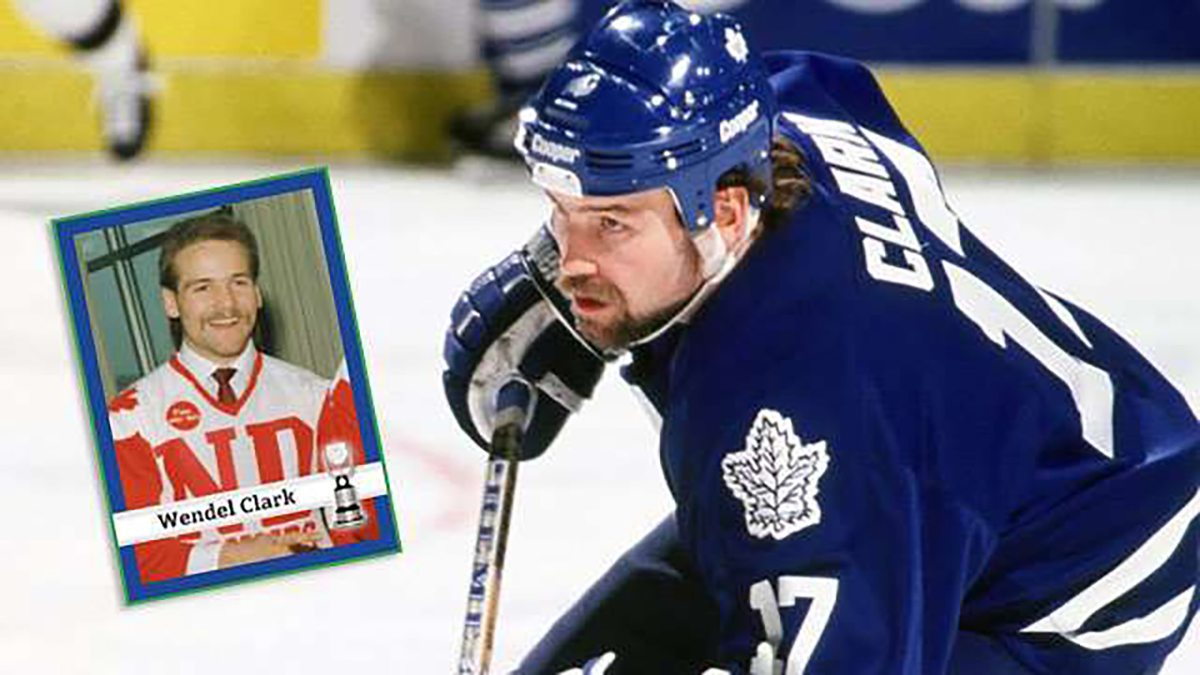

“Jon Cooper came out to tryouts and he was talking to the guy next to him,” O’Malley starts his tale. “Jon had played AAA bantam in BC and the guy he was talking to had only played AA in Kelvington, Saskatchewan. The puck dropped and they went back and forth a little bit but before he knew it Jon was looking up at the lights lying on his back on the ice. The guy he was up against was Wendel Clark.”

That’s not the only Wendel Clark story you’ll hear either.

“We were having tryouts for our U17 team, we had guys running practice and I was in the stands with Barry MacKenzie,” Lockwood starts. “Kids were doing simple one on ones and one of our top players from the year before went against this kid and this other kid, who we didn’t know, blew him up. So, next time around, we see this kid from last year skip the line to face him again and he gets blown up again. Barry and I are going through our sheets to find out who it was that was just dominating out there – and his name was Wendel Clark.”

MacKenzie, Brind’Amour, O’Malley, Collins and many others describe it as the best years of their life.

“That ’88 team, you’re never going to find a group like that again, ever,” Brind’Amour believes. “I think 17 of the guys ended up getting scholarships, it was just like the National Development Program in the US right now. That was how good we were.”

The team won 53 games in the 60 game SJHL season, beating Yorkton in the league final, sweeping Winnipeg for the Anavet Cup and knocking off Calgary for the Abbott Cup.

In the Centennial Cup, the team rallied from a 2-1 deficit going into the 3rd period to beat Halifax and capture the Canadian championship.

Brind’Amour was chosen as top centre, top scorer and Most Valuable Player.

“We had a lot of fun moments winning a championship in 1988,” Gauvin, who roomed with Brind’Amour, says. “It’s funny though, I can’t give you a lot of game specifics, but I can give you a ton of great anecdotes. That’s the beauty of it. We have had years with those players to relish in our success and the relationships we’ve formed.”

“You’re coming from all over the place, you’re homesick, you are on your own for the first time and you’re going through that together,” Brind’Amour reflects. “You all have a dream that you all want to move on in hockey and you want to get better and it’s an incredible place to do that.”

================================

The hockey landscape has changed dramatically since 1988.

The academy model has come in swinging and is not going away any time soon. The advantages of seemingly unlimited ice time, dedicated coaches, classes around hockey knowledge, amalgamated schooling – it has a tremendous number of benefits.

The landscape at Notre Dame has changed too.

The school looked to its alumni to guide the school forward, bringing Stephane Gauvin back as principal this year.

To anchor the hockey program, they went outside their walls – but not very far.

Dave Struch was hired as the new Director of Hockey in July of 2023.

Struch held many roles with the Regina Pats for eight seasons, before then in many similar capacities with the Saskatoon Blades. He’s been to three Memorial Cups and worked with Canada’s U-18 World Junior team in 2019 and 2022.

Struch’s mindset is on evolution.

“We are trying to get back to winning hockey games and being competitive, but we know at Notre Dame the one thing we have always done and will continue to do is develop people. That’s established.” Struch explains. “This place will be come an elite athletic centre, not just for hockey.”

If evolution is the word Struch uses most, elite comes in at a very close second – and that is by design.

“We are all here for the elite development of people, that’s the most important thing,” Struch says. “The process that we execute has to be elite and we have to start using those words and that comes from us first, as leaders. The hockey, the academics, the enrollment, how we carry ourselves, we have to take big steps to stay elite.”

“Getting everyone in the same mindset that we are going to develop elite people, it’s an incredible opportunity to use the athletic route,” Struch goes into detail of his plan as he continues to learn on the job. “These athletes don’t play their sports till they are 50 or 60. Their athletics stop at some point. We are developing leadership, athletics, independence, maturity, character so they can become incredible people in whatever avenue they take.”

Struch points out, this is not a change, acknowledging how much the school already does at a very high level. If anything, it’s a shift in thinking to those two key words he uses regularly.

“Team first is real, we before me is real. There doesn’t have to be gigantic words. It’s a real thing. The players get to control what they control – work ethic, compete, intensity, drive and energy and it’s our job to challenge them and put them in positions to execute all that stuff at an elite level.”

By his own admission, Struch has gone so far outside his lane as a Director of Hockey. His confidence talking about the evolution of Notre Dame is evident, speaking about taking steps to bring in skill developers, nutritionists, power skaters, trainers et all.

All with the primary focus of elite development of player and person.

“We want to bring in quality players to provide more wins – and that’s not in the win-loss column – it’s in the day to day creating leadership, character and hockey IQ because that’s part of the process,” Struch explains. “The rewards show up in the win-loss column at the end. We want to bring in quality athletes and have them leave as quality people. If we can get these athletes here; the people they will grow into will be their best part of Notre Dame.”

“Hockey is just a vehicle for character development, learning things like resilience, adversity, hard work, conflict resolution and how important relationships are with your peers and your coaches and your teachers,” Gauvin reiterates. “It was foundational for me, and I know it will have that effect on everyone else who comes to this school.”

Both are in sync with the same big picture.

Hockey isn’t lasting forever.

“Hockey is a microcosm of life,” Gauvin believes. “I’ve said in education for years, we are always one phrase away from turning a kid off forever – it’s a daunting responsibility and we have to be so careful of that, but it’s also an awesome responsibility to have a lifelong impact.”

“They are going to develop as people, they are getting educated in the classroom, they are becoming independent,” Struch piggybacks. “On the hockey front, I want them to learn to be a teammate, to work in a team environment, to make mistakes and learn from them and also have successes and learn from them. I want these student-athletes to feel that.”

He highlights that from his own backyard, a father of three – ages 11, 13 and 15.

“I know what these families are looking for,” Struch admits. “I’m looking for the same for my kids. We can provide these athletes with something really special that no other program can. We are one minute from everything. Food, dorms, school, gym, ice – it’s non-stop, it’s consistent. It’s remarkable.”

================================

It’s a great decision for a family to send their 15-year-old to another city, another province, another country to pursue a dream.

Rod Brind’Amour went with two other students to Notre Dame, sharing it wasn’t much more than a leap of faith.

Players and students learn together, eat together, live together and grow together – there isn’t much else for them to do in Wilcox.

But they come to wear the red gloves, they come for the tradition.

They come to be elite.

“We are in a position to use one of the best facilities in Canada in an effective way to become an elite athletic program, not just hockey,” Struch pictures.

“There is no bullshit here, it’s real. It happens daily. The best part is, everyone screws up and no one cares. We move on to the next phase, we as leaders provide direction – what’s better, what could you do different and let’s try it again. The students come here and take ownership of it because that is what develops them and that’s what they become.”

Struch never played at Notre Dame, Collins couldn’t wait for her time and numerous alumni talk about the place like they were running the halls yesterday – even if it was over 30 years ago.

“I have a feeling of pride being a Saskatoon Blade, I was a stick boy there, then I had a chance to play in a Memorial Cup there and then I got to coach there. There is a great pride in that, the Regina Pats, the same thing.” Struch reflects. “It’s not just the size of Notre Dame or the years of development, it is heartfelt when you speak to a Hound. My hair stands on end when I talk about it because I believe in that part of sport.”

It’s a storied program, a storied campus and an evolution waiting to happen.

It’s also possible you could drive right by it, but that’s ok. That’s hockey in the prairies.

“When you drive in though and you see the campus. It’s a small little college,” Struch exclaims.

“It’s a beating heart in the middle of a field.”