“...the dream is to bring a kid through skating school to the KHL one day.”

Hockey Factories FREE E-book: A DEEP DIVE INTO THE WORLD’S TOP HOCKEY FACTORIES

***

What kid didn’t play cops and robbers when they were young?

You and your band of thieves stole any number of items: money, diamonds, or perhaps even something more sacred, another kid’s toy.

The other group upheld the law, bringing the crooks down in a good old fashioned footrace, tag them and right to jail they went.

We played that until the streetlights came on. Hours on end.

Students at the Jokerit skating school are playing the same game today, just on ice.

“The best way to teach skating was trying to keep it as playful and enjoyable as possible,” says Tuomas Taskinen, Jokerit U13 head coach. “When you’re teaching a skill at the very basic level it’s not good to have a competition. You need to have basic knowledge and skills so you are able to compete, but quite often it gets competitive because of the kids that are involved and it fires them up.”

The Jokerit skating school starts with boys as young at four-years-old and entertains them with games like “Who’s Afraid of the Ice Man” or their own version of Red Bull Crushed Ice courses with fire hoses, small boards and other obstacles in their way.

Taskinen has taken on the U13 coaching role after going through the ranks with each age group, starting with U7, when the Jokerit program first begins.

“When we start at the beginning of the season, if we have 50 kids, maybe a third of them are ok with skating,” explains Mikko Nurminen, Jokerit Director of Youth Coaching. “Then there’s a middle group who can move, and you can start doing things with them. Then there’s the group who can’t skate at all.

“We try to get the last group moving so they can participate and once we do that, we start doing fun games like tag or cops and robbers. We try to be very supportive and make it fun, so they want to keep going.”

For some, their experience with Jokerit may end at skating school as they choose to try other sports. For others, they will spend the next decade of their lives growing through Finland’s most prestigious hockey development program.

The Joke of the Jokers began in 1967.

Junior hockey has always been an important part of the Jokers for the last 50 years, when the program captured its first Finnish Junior Championship in 1973.

Finland, a hockey crazy country to say the least, couldn’t get enough.

The junior leagues started to fill up and ultimately the idea of a skating school became reality in November of 1994. Since then, thousands of players over 30 years have fallen in love with the game through the supportive approach of the Jokerit coaches and instructors.

Players who graduate from the skating school could make their move into the U7 program and onwards, with the Jokerit juniors rounding out at U20.

As the Director of Youth Coaching, Nurminen is their first point of contact.

“It’s one of the best things in my job, Saturday morning skating school,” Nurminen says. “Most of the time they are really happy, but they are also really honest, so it’s a positive challenge to make them feel comfortable.”

“One of the big things that I like with Jokerit is that the hockey directors want to underline the values of the club and that goes not only with the coaches and players, but also with parents,” Taskinen adds. “We talk to them about how they should support their kids. It’s ok if in U7 there’s a Saturday morning where the kid is tired and he’s not willing to come to practice. It’s ok, we don’t push it too hard, we’ll try next week.”

From then on, it’s constant development.

“I think we have tried to help the kids go as far as possible,” Nurminen states. “At the beginning it should be really fun and still make you better every day, so we try to introduce new things and bring that in as we challenge ourselves to do things a bit earlier or what is the right order.

“The first games we have are in U7, but it’s half ice until U10,” Taskinen explains. “If you look at the big picture, the period they are in that range there are three main goals: they have good skills in skating and stickhandling, so they can carry the puck and lift their head and see where they are going, and that their attitude towards the game is positive.”

That is done methodically, they are not throwing information at kids from all directions and are not necessarily trying to develop the best 10-year-olds in the country.

Their development process is deliberate, it’s functional and it’s direct.

Any feedback given to the players in that age group at that time is specifically focused on the type of area they are trying to improve with that practice or drill.

“Once the boys go to full ice, we approach teaching hockey in four ways from a game point of view,” Taskinen shares. “Offence with the puck, offence without the puck, defending the puck carrier, and defending the player who doesn’t have the puck.”

“I think it’s helped that we only focus on the goals and feedback from that particular area,” he continues. “If we are trying to improve their game as a puck carrier and we give them feedback on their defending, it mixes up everything.”

Their timelines at first could catch a North American-ized parent off guard. Taskinen would go on to explain they don’t start teaching how to defend the player without the puck until U12.

In some circles around North America, there are teams watching kids that age in some form of recruiting. When I asked Taskinen which of the four parts of the game was the easiest to grasp, his answer was no surprise.

“The kids want to have the puck,” he said. “The second easiest is how they are defending against the guy who has the puck, because they want to get the puck. When we go to full ice, we talk about how you should move on the ice when you are playing forward, how you can help the player who has the puck with your movement. The hardest is getting them the idea that it’s really hard to defend if you’re looking at the puck because usually the puck carrier is not the most dangerous person in our zone.”

That message is consistent throughout their growth for players within the Jokerit club because, for the post part, from U7 to U12 they have the same coach.

Nurminen runs the hockey schools and skating schools and will be the U7 head coach until January or February of that season. It’s then handed off to a parent coach or someone who may stay with that group over the next few years.

It creates a line of communication and level of comfort between the coaches, players and parents that is at the heart of Jokerit’s success.

“What we have tried to tell them, from the very beginning, is we have praised effort,” Taskinen says. “If nobody makes a mistake in a hockey game, that would be a very dull game. What I would like to see when they are on the ice is they show effort, which creates competitiveness, and it gives them tools to face adversity because there will be that in many aspects of their life.”

“The other thing we have underlined many times is don’t be afraid of mistakes,” he continues. “If you make a mistake, don’t worry about that, I’ve done that a thousand times, so has Michael Jordan. But the idea is when we make a mistake, we try not to worry about it, but we talk afterwards about what we can do differently, but what is done is done, the past is what it is, and we try to control the things that are controllable.”

***

Skill development takes the lead at every age level you examine with Jokerit, but you see it start to take off around the U13 level.

Back in 2013, the Finland Ice Hockey Federation launched a skills coach project.

It was a three year investment leading up to the World Championship to try to start improving junior hockey across the country.

Essentially, the Federation paid 50% of the full-time skills coach’s salary, while the club paid the rest.

The program has been extremely successful, now entering its ninth season.

“It has helped a lot because we’ve been able to hire someone for that role and the fact that we have more people who are full-time is a big thing for us,” says Olli-Pekka Yrjanheikki, Jokerit’s Director of Coaching. “The more important thing is how it brings our cooperative clubs closer to Jokerit. We have great relationships with our cooperative clubs and Jokerit is aiming to have the best players from those clubs when they are U15 and U16.”

Each program who takes advantage of the project is required to have a cooperative club network; Jokerit has nine clubs and over 3,000 players within their system.

Their slogan: “Developing together the quality and image of local hockey.”

Teemu Poussa is the man who has benefitted as skills coach for Jokerit.

He spends a large portion of his time working with the three cooperative clubs in his region and with the U12s, and onward with the parent club.

“We are trying to coach those players in game situations and go more in depth,” Poussa says. “We have some goals in every role that we are trying to progress year after year. Our big goal when they move from my phase to U16 is that they have certain skills in every role.”

When Poussa starts working with the players is when they are hoping to grasp all four concepts of the game and be able to play that way all over the ice.

“We are trying to concentrate on one skill or one role in a practice, so then we have a certain skill or thing that we want to see from that practice,” Poussa explains. “We will create competition in practices, we will score points or do bets for their age group and post winners on Instagram and it really helps. We plan our practices in a good way to include the things we want to see from those roles.”

“Sometimes we think too much about the games; my opinion is the practice matters,” Poussa continues. “We are normally playing once a week in my age group and my U15 program practices four times a week, so that’s why it matters what we are doing in practice and how can we develop those skills. We create different environments – sometimes you have one minute left and you’re one goal behind, so my vision is practicing those situations, so they are ready when they do play games for those scenarios.”

“Winning should matter in the practices,” Poussa delivers. “As an example, 2v2 is the best game, in my opinion. You can’t hide there. If you want to score you have to help and if you need to defend you have to know how to defend both guys. So, then we look at how we help the puck carrier, how we create 2 on 1 situations in every area of the game, how are we scanning the ice and understanding the game; does the puck carrier need help in the attacking zone?”

Poussa sees his role as coaching the coaches. A theme that is echoed throughout everyone in Jokerit’s front office.

“Working with both our big club and the cooperative clubs it’s important we have a goal in mind,” Poussa points out. “We have the cooperative clubs, and we have coach education with all of those coaches too, to help them learn and grow. I would say the biggest thing is that I see these coaches and teams weekly, so we see how they have done, how the players are developing.”

Overseeing a large group of players, coaches and teams means communication has to be at the forefront.

That’s where Poussa and Nurminen collaborate.

“Mikko and I write the weekly message for the coaches,” Poussa explains. “It has our schedule, will talk about the last week and there’s also coaching notes that could be a video or an article. I think that’s been a really good part and it’s been a great way to bring some research and opinions to everyone.”

“It’s communication from us to the teams, but it’s also to the parents, and from the teams back to us,” Nurminen includes. “The best teams and coaching groups we have work with communication. We have about 500 players in Jokerit if you count the hockey school, so there are a lot of different opinions. We have to communicate really well.”

***

Jokerit also has a secret weapon in its back pocket.

A man who created a career for himself on the ice, but in a different sport.

For many Canadians, Victor Kraatz is a legend.

The 10-time World Champion figure skater captured hearts across the country, with partner Shae-Lynn Bourne, from 1992-2003, just missing the podium at two Olympic Winter Games.

After his skating career concluded, Kraatz put that part of his life behind him. But he always came back to the ice.

“I went back to school and was studying marketing,” Kraatz explains. “When I stopped competing as an athlete, I sort of said ‘that’s it’ and walked away. I did that partially because I needed to find out who I was.”

“I was working for the Vancouver Whitecaps and at the time they had a coach who was giving our organization a pep talk and I’m sitting there thinking ‘what am I doing?’ I went home and there were all these ideas in my head. So, in 2010 I did some Olympic coverage for CTV and was watching the hockey games and I was just trying to think of how to get started.”

Chance meetings seemed to have followed Kraatz since then.

While working at the North Shore Winter Club in North Vancouver, Kraatz was approached with the suggestion of working with a young player, who he didn’t know at the time. They set up a meeting and a relationship was born.

“The kid showed up and it was Mathew Barzal,” Kraatz tells. “At the time he was playing for Seattle and so I said ‘let’s work on stuff and you tell me if you want to do this or focus on something else and let’s see if this is a good match or if you are way beyond my skills and then we just walk away.’”

“We always kept the door open that if either of us feel like we are out of each other’s leagues we just walk away, but it never happened,” Kraatz remembers. “Right away, I was thrown into this opportunity because he’s so intense and hard working. That’s how my name was thrown out there and word got around. It was his first year with the New York Islanders and he won NHL Rookie of the Year and we had a few more sessions after that. I still text him to see how he’s doing, and it’s become a really special relationship.”

In another occurrence, Kraatz was invited to put on a clinic in Helsinki and afterwards was asked if he would be interested in doing some work for a team. The two parties exchanged information and a few months later, they reconnected, and he was offered an opportunity to join the club.

That meeting happened to be with Kim Borgstrom, Jokerit junior club President.

“When I met him and learned why he was moving to Finland, I told the board that we have to keep him,” says Borgstrom. “Victor has brought a lot of knowledge to the club, it’s interesting to see how he was doing things in North America. He was one of the best skaters in the world. All the players I know that have worked with Victor, love him.”

“The one thing that Jokerit always pride themselves in is being a fast team,” Kraatz details. “Carrying the puck as fast as they can to get into the O-Zone, so that is always in the back of my mind. The danger of that is when you have kids spinning their feet, they are very agile, but they are not able to cover the ice. The balancing act is you need kids who are agile and moving their feet, but they still need to be able to cover the ice.”

“Balance is key in a lot of ways. I don’t want to be the same as a coach, I want to learn new skills and you do that by watching other people or listening to other people,” Kraatz says. “I don’t want athletes to think ‘I know skating is important, but what does that mean if I can’t handle the puck.’”

“You can run a fitness class and do drills down the ice until you’re blue in the face but how does that translate to a game like scenario. It’s always with the intent of being game relatable. I see too often where coaches will do some crazy stuff and think ‘wow that’s fantastic but is it going to hold up in a game.’”

This is Kraatz’s third season with the club. It’s a completely different dynamic of players and styles from Finland to North America, and Kraatz credits the people within Jokerit for making this such a smooth transition.

“The coaches are always open to suggestions or questions that I have, and I would say ‘this is what we would do in Canada’ and he would come back with ‘yeah, that wouldn’t work here,’” Kraatz shares. “So, you learn their coaching philosophy and we’ll tweak it and that gives me a great opportunity to learn about their hockey culture and it’s a great overlap of me learning a lot from them and hopefully vice versa.”

“I’m here for a very precise mandate – keep the kids fast, keep them agile, teach them the technique, draw from past experiences and whatnot,” Kraatz explains. “With the younger kids you simplify it. Generating power, changing directions, quick steps but always with the puck. With the older guys, there are two kinds – the player who has been a professional for a long time and there we try to make them as good as they can be at that stage, and then the younger guys who are still learning multiple different ways to do things at a high speed. It’s more detail oriented, but I leave their certain style and my task is to find the way to make them the best they can be.”

It speaks to Kraatz’s coaching style, knowledge and skill to not only have success in his previous career, but to translate that into hockey.

But that doesn’t mean it’s been all smooth.

“I remember we did this one drill with Matt and he said to me ‘I want you to pass me the puck’ and I’m going back to him, ‘no I don’t think you want that,” Kraatz laughs. “But he comes back to me with ‘it’s actually good, I’ve got to get a shitty pass sometimes.’”

“There are plenty of skills coaches in Finland so there must be something I’m doing that makes me stand out and I’m never tired of learning for that reason,” Kraatz follows up. “With a team setting, I ask questions, I ask why and try to fill in the blanks for some of the intent because I didn’t play hockey at a high level. That has worked fantastic and the trust we have in the organization is incredible.”

***

You speak with any member of the coaching staff within Jokerit and the message is the same.

It’s remarkably impressive how from age seven to age 20, the development model stays consistent.

Consistency is key for this club, and they’ve had plenty of it – starting from the top.

President Kim Borgstrom has been with the board for 30 years, Mikko Nurminen seven years, Tuomas Taskinen around the same.

And Olli-Pekka Yrjanheikki has been a member of Jokerit for a decade.

Yrjanheikki, who thankfully did not ask me to attempt to pronounce his last name, is affectionately known as “OP.”

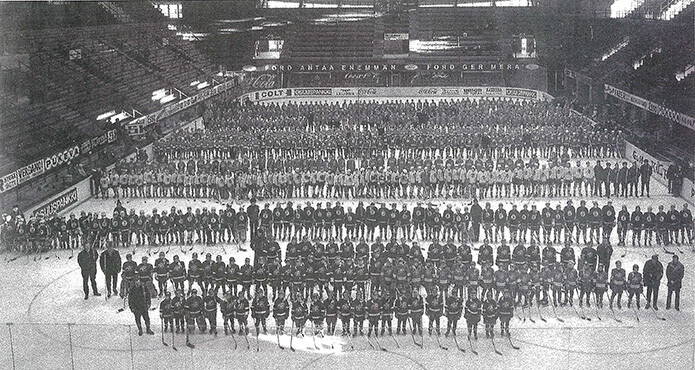

As the Director of Coaching, OP (top left in photo above) oversees the coaching staff under three values – cooperating, continuing development and commitment.

“Five years ago, we identified how the team would play, four years ago it was how to help individual players improve their skills and now, for the last two years, we have talked about leadership and how we communicate with players,” Yrjanheikki explains. “That wouldn’t have been possible if we didn’t have all these coaches here for so long. Coaches are one of the best assets of the club. The big thing is the board of directors have the patience to give us time to make progress in our development. For instance, Tero Määttä (U20) is in his fourth season, Niko Halttunen (U18) his fifth season and Tuomas Kalliomäki (U16) is in his 11th season with the club.

“Jokerit has had great coaches and great players throughout its history,” Yrjanheikki admits. “But every age group had been a different unit 10 years ago. Now we have a group of coaches not just for an age group. They follow our age groups. Every team knows what the players in our system are doing and what the players can do as they go through the program. The club culture has gotten stronger because of that.

“We have a community of coaches, not just a group of coaches,” Yrjanheikki continues. “We meet quite often with our coaches, and we discuss our values. All the coaches can discuss and decide what appropriate action we need to take. What does the goalie coach do to achieve those values? What does the head coach do to match those values? Then, the coaches can see their opinions are being heard.

“The brand of Jokerit is big, but we are a small club so it’s easy to affect things and change things pretty quickly. The organization is flat and agile for decision making,” Poussa celebrates. “We have really good coaches and that really motivates me. The best thing about it is this still doesn’t feel like work. The environment is what makes Jokerit so special.

“Coaching is organized so that most of the coaches in Finland and our team are father coaches until U13-14 and then there will be pro coaches,” Taskinen includes. “There are several workshops for the coaches every year, Teemu is on the ice once a week and the idea is not so much to teach the kids, but to have a conversation with coaches and spur them on. I think for the past 10 years the club itself has organized really well and that is one of the key things that separates us from other teams.”

Yrjanheikki and Jokerit have a competence-based framework for coaches. It’s how they are evaluated and how coaches can identify where they want to improve.

It consists of self-development skills, people skills and substance skills.

“My main goal is that we have the best coaches in our different levels and that the teams know every day counts, so we see the individual player improves here,” Yrjanheikki explains. “We can monitor that improvement many other ways: by how players are improving, how our teams succeed and how many national team players we have. Those are the things that will prove if we are doing a good job or not.

“The atmosphere within the coaches is the main thing, for me,” he continues. “The fact that we have the opportunity to keep the same coaches here. I like to think talented players are willing to come to Jokerit because we are famous for the way we treat players and how we communicate. It is our job to show the players how to live the professional lifestyle. How to sleep, how to work in school, how to take care of themselves. It’s so important that they communicate with us, their teammates and coaches and that they can listen to feedback even if it’s negative. When that player looks in the mirror, he knows that he is the one person responsible for his career.”

***

Jesper Tarkiainen is one who could tell you a better story about Jokerit than I could.

He lived it – from skating school all the way to the University of Vermont, where he’s currently enrolled in his freshman year.

The format worked for him.

“It was very easy because all the friends are the same and we go from year to year with the same group and same coaches, so that makes it easier,” Tarkiainen explains. “For us, it was in U15 when two groups got together into one team and when there were actually cuts and it started getting real and competitive. Before that, we played as two groups and there’s a lot more guys in the program until that point.”

The trademarks of a Finnish hockey player are their speed and their skill, which has suited Tarkiainen throughout his development.

“We were always skilled, always staying on the puck, we never dumped the puck, and we were always taught to stay on the puck as long as you can, try to make a play instead of just giving it up,” he says. “We did a lot of skating and a lot of edge work, all the way from skating school until when I was done with the program – more skill than grind. I enjoyed playing that style, I was always a smaller guy growing up, so that was good for me.”

Tarkiainen won a national championship at the U15 level and in his second season with the U18s. Now playing for Todd Woodcroft in Vermont, he says a lot of what he was taught as a kid has translated.

“I think the biggest thing is in every practice the level you have to perform in is always high,” he states. “You always have to give your best and if you give bad passes or don’t move your feet, you hear about it. Every practice you have to be good and that’s the mindset that Jokerit taught me.”

***

Tarkiainen is a model of what Jokerit is hoping becomes the norm.

Introduce them to skating, get them playing in their younger years, progress through the system and one day, hopefully join their big club in the Kontinental Hockey League.

Jokerit is the first Finnish team to join the KHL, which they did in 2014. Of the 24 member clubs in the KHL, 19 of them are based in Russia.

Since joining the KHL, the team has qualified for the playoffs every year, but has not advanced past the 2nd round.

To do that, the hope of all involved with Jokerit is that it will be their own players that fill that roster – but there’s a tough bridge to gap.

“The negative thing is we are struggling to keep our most talented players when they are 19 or 20-years-old,” Yrjanheikki explains. “They are thinking it’s too big a step to go from U20 to KHL, so they will go to Liga teams or North America, but the dream is to bring a kid through skating school to the KHL one day.”

Club president Kim Borgstrom agrees.

“Our goal is to see Jokerit junior players take the next step to get into the KHL. You have to take a step somewhere else to get into the KHL right now, but that is one thing I’d like to see one day. The step from U20 to the KHL is huge, but on a big scale, I want to see more Jokerit players on the KHL team.”

Janne Vuorinen lives that challenge every day.

As Director of Player Personnel (essentially Assistant GM for the KHL Jokerit club), his role is to hire coaches and recruit players to the U20 and KHL club. He also oversees the junior organization and coaching managers.

“During the time Jokerit has been in the KHL, I think we’ve put even more focus on the junior system and we’ve invested more money on the coach’s side,” Vuorinen says. “It’s a little bittersweet that sometimes the benefit goes to some other team because we create good players that play for other Finnish teams, but more and more in the coming years, more Jokerit players will be coming to the KHL team.”

“As an organization we would be very proud if some of our players were in our skating schools and went all the way up to our U20 program,” Vuorinen continues. “I think that’s a big accomplishment for our system and all of our coaches who have helped that player along the way. If they do leave, we try to stay in contact with them and keep those relationships with the players so if they develop for the KHL level, then we can bring them back and they can still be proud of the Jokerit program and their journey with our junior teams.”

Vuorinen sees coaching stability and development as keys to getting those players there.

“The team first mentality comes right away, we tell them in U7 we have to do this together and that doesn’t matter if it’s between the coaches in U7 or the KHL team, they need to work together,” Vuorinen assures. “They really understand the Jokerit logo is the main thing. We believe if we work together, it’s much easier for each individual to improve and move on with their careers. The main thing is we want to have a good character team and a good team chemistry. We don’t want to hire good players if they are bad people.”

***

Vuorinen’s boss is one of the most well-known people in the country. His name also carries a lot of weight in Canada, especially in Edmonton, Alberta.

Jari Kurri played in Edmonton for 10 seasons, helping the Oilers win five Stanley Cups in that time, amassing 1,043 points along the way.

After his Hall of Fame playing career, Kurri returned home and worked as a General Manager with the Finnish National team.

In 2013, he came back to his roots, joining Jokerit as their GM and President of the men’s team.

“It’s a great story for myself when I started as a nine-year-old joining Jokerit,” Kurri remembers. “When this opportunity came, I thought ‘wow, this is perfect for me’. Also, joining the KHL team and having to learn how to play in that league, it was a challenge that I really enjoyed. To come to Jokerit in this role, it’s great. I enjoy every day.”

While Kurri’s job is to build up the KHL team, he sees the work being done at the junior level and looks forward to seeing the fruits of those labours as the players start stepping into their professional careers.

“I think it’s great we have coaches that stay with the kids for three or four years, they then know the players and they have an open mind,” Kurri believes. “All the coaches are together, on the ice or in the office, so we learn from each other.”

“It’s good for us that our coaches discuss with the junior coaches and try to bring what the game is about at this level and figuring out what direction the game is going and what type of players you need,” Kurri agrees. “I think in the last few years our program has gotten really good in the juniors. They are putting a lot of effort into improving the junior program and hiring good coaches and I think it’s going in the right direction.”

“We have gotten respect in the league that Jokerit is a good hockey club and tough to play against. It’s good for us that we are building a reputation like that.”

Kurri has his own goals for the KHL club, ones that any GM would look for.

“We have had good success in the regular season, but we need to get that next step in the playoffs,” Kurri states. “It’s not easy because if we go past the 1st round, we are going to face the top team in the league, so it’s not easy to get past there, but that’s our goal now.”

***

You cannot develop players, under the same model, with similar skill sets from age six to age 19 without the three C’s that Yrjanheikki had described earlier: cooperating, continuing development and commitment.

“That’s the fuel for me. To see how the guys develop and now as they grow from boys to young men, to have those connections are so important,” Taskinen recalls. “I remember when I was their age the mentality was the coach was a big authority and that you never started a conversation with a coach. So to create an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect is great; I’m more than pleased when some of the guys start joking with me – not at me – but with me and I think that shows there is a trust and that is really important.”

“The big thing for us is we want to emphasize our coaches,” Vuorinen explains. “OP, Teemu and Mikko are doing a great job with that. We see what kind of hockey is happening at the best level and we try to develop players to be ready for that, and same with our coaches.”

“I take a lot of pride that the coaches and employees really like the organization and want to stay with us. If they can get a better spot for their career we are happy for them, but we are very proud when they want to stay with Jokerit.”

“For me, it’s in my heart,” Borgstrom shares. “It’s like a family. Both of my older brothers played for Jokerit. My son’s NHL agent played with my brother. It’s great to see old guys come back. It’s a big family. It’s my lifestyle.”

The fire that coaches are trying to develop in their players is obvious within them, as well.

“I’m competitive in a way,” Nurminen admits. “If I feel there is someone at another club doing something great, I challenge myself to become better. I want to be the best at what I do. I take pride in our program and what we do here. I want this to be the greatest hockey program, doing what we do. That gets me going.”

“OP knows a lot about the game, he studies all the time,” Poussa points out right away when asked who he’s learned from along the way. “He has to be one of the best in Finland, from the junior side. From Mikko, I’ve learned how to communicate with the parents and other people in the organization. I want to see Jokerit be the best player developer in the next three years. I don’t have huge aspirations, but I want to be the best skills coach for these age groups.”

And with NHL Hall of Famers, lifetime coaches and a country filled with alumni, the man who oversees this historic junior program can’t help but go back to the beginning himself.

“Hockey is a way of life for me. I just love hockey, it’s not a place of work for me. I get inspired when I think I have helped a player or a coach somehow or someway,” Yrjanheikki says with a smile. “Whenever I have a feeling that I have helped a player or coach, that brings me joy and that’s why I’m here.”