“Everybody loves playing here, that’s the saddest part of it. Hockey works here in the desert. It works in Arizona.”

Tyson Nash, an NHL veteran of 374 games including 69 in Arizona in the 2003-2004 season, sounds defeated as he mutters those words over the Arizona Coyotes broadcast on Bally’s Sports Arizona.

With that you hear the PA announcer inside Mullet Arena let the crowd know there is one minute left to play – not just in the current game they are attending on April 17th, 2024, but in the history of their beloved franchise.

Fans and broadcasters alike wipe tears from their eyes as the final horn goes.

Although the Arizona Coyotes beat the Edmonton Oilers 5-2 that night, no one really won.

As the team packed up to relocate there was excitement about what Salt Lake City would hold for them. Season tickets were sold in record time and ownership appears stable and willing to make this a profitable and viable NHL organization.

The people of Arizona, however, were left with questions to which no one has the answer.

The heartbreak of losing a professional sports team and the memories that went along with it is real and it's deep.

This is not a story about a debunked NHL team in an unconventional market that countless people from outside can tell you won’t work.

This is about a 10-year-old lacing up their skates at the Ice Den in Scottsdale to take the ice with dreams about becoming an NHL player like Auston Matthews, Matthew Knies, Mark Kastelic, Josh Doan and many others. Players from their hometown and made it to “The Show”.

This is about growing the game around the world – conventional or unconventional.

This is about a club that, while their NHL idols moved over 670 miles away, still thrives and is producing the next generation of great players.

This is about hockey in a desert.

This is the Arizona Jr. Coyotes.

================================

In 1996 the NHL’s Winnipeg Jets shipped out and moved from one of the coldest cities in the league to one of the warmest.

The Phoenix Coyotes lost their first game in franchise history 1-0 in Hartford against the Whalers before winning their second contest in Boston 5-2.

With a line-up of players like Keith Tkachuk, Shane Doan, and Nikolai Khabibulin, the Coyotes made the postseason their first year in the desert, losing in seven games to the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in Round 1.

Along with the team’s creation came a number of establishments, including the Ice Den, which will play a prominent role in this story.

There may be no one more enamoured with the team than Brian Slugocki.

“I was born and raised here, born in 1991. The NHL team came in 1996, I was at the Ice Den the day it opened in 1997 and was one of the first kids ever on the ice,” Slugocki recalls. “I played all my house and travel hockey at the Ice Den. I actually got dressed in a trailer in the desert because the dressing rooms weren’t ready yet.”

Slugocki went to school at the University of Arizona as well, so he spent 13 years in the area as a player and then coached within the Jr. Coyotes program for nearly a decade.

If you’ve spent any time on The Coaches Site, you’ve seen Slugocki's outstanding skills work, drills, or presentations, like at TCS Live in 2024.

“I remember when the Coyotes were first coming into the valley and doing the White Outs and that’s when so many of my friends and myself got into it,” Slugocki says. “It was a crazy environment during the playoffs.”

As the team’s popularity began to grow merchandise started to sell and interest in hockey overall began taking root.

“For a while there weren’t a lot of high-end teams. It was a lot of AA teams but it was the Coyotes practice facility, which we are still at – Ice Den Scottsdale,” Mike DeAngelis explains. “At the time they were building their youth program to match the NHL franchise. So I took the job as Hockey Director with the Jr. Coyotes and coming up in January 2025 I’ll be on 20 years employed with the club.”

If Slugocki was born with Arizona hockey in his blood, DeAngelis has injected that same spirit into hundreds of kids during his time with the club.

He played college hockey and was an NCAA All-American, played for the Italian National Team three times in the Olympics, and was a part-time scout for the NHL’s Arizona Coyotes for four years.

At the beginning of the Jr. Coyotes journey there was one major problem DeAngelis had to solve.

“It was said to me "how do we get these kids to stay here and play in our rink so we can become the best youth program in the market?" We had the logo and the facility, but the top players were going to different rinks in Phoenix. I was asked to build a program that offered AAA teams so we could go to the top of the pile for local kids who wanted to stay in our program an pursue their dreams.”

In some ways the history of AAA hockey within the Arizona Jr. Coyotes program sounds like the start of the joke.

What do you get when you cross ice hockey in Arizona and Asian cuisine?

“There was a Tier 1 AAA team in town that offered a couple midget teams, and it was called PF Chang’s Hockey – as in, the restaurant PF Chang’s,” DeAngelis explains. “I am good friends with the man who was running it and we ended up transporting the team inside the Jr Coyotes program. We kept it as the PF Chang’s name, but it was the cherry on top for the Jr Coyotes program, so you went up through the Jr Coyotes and if you were really good you made it up to the PF Chang’s club. It was a different jersey and all that.”

One of the players on those PF Chang’s teams was Brian Slugocki.

“I remember vividly when I was on the U16 team with PF Changs, which was great because somehow we got free food when we were on the road,” Slugocki laughs.

PF Chang’s was run by an ex-teammate of DeAngelis, Jim Johnson, with whom he initially spoke about joining the program. When Johnson decided to move on and pursue his coaching career, he left the PF Chang’s teams behind and they were all joined under the Jr. Coyotes name in 2010.

A veteran of over 800 NHL games, Johnson made several NHL stops along his coaching journey: Tampa Bay, Washington, San Jose, Edmonton, and St. Louis. He currently serves as the Director of Player Development for the Anaheim Ducks.

================================

The moniker was there with the NHL affiliation for the Jr. Coyotes to control the market for youth hockey in the state of Arizona.

The next – and ongoing to this day – challenge was to get kids to want to go into an ice facility when it’s still 20 degrees Celsius/68 degrees Fahrenheit outside in January.

For some, like Slugocki, hockey was something they were around all the time.

“My whole family is from Chicago. I have two older brothers so I was always playing catch up and I was always playing multiple sports but baseball is too slow for me and I’m not a marathon runner, so the fast, quick, explosive nature of hockey always fit with me,” Slugocki reflects. “My dad never pushed me but he was not upset that his son wanted to play hockey and we got to share that together.”

Mark Kastelic had a similar upbringing.

“I have a Canadian background, both my parents are Canadian and on my mom’s side my grandpa and her brother played in the NHL and my dad played in the league as well, so it was always destined that I would lace up the skates at some point,” he suggests.

Kastelic was born in Phoenix three years after the Coyotes came into existence.

His father Ed played over 200 games in the NHL, his grandfather, Pat Stapleton, played over 600 games in the league and is the namesake of the Pat Stapleton Arena, home of the Sarnia Legionnaires of the GOJHL in Sarnia, Ontario, and his uncle Mike logged almost 700 NHL games.

Kastelic started playing hockey when he was around 6 years old and as he got more and more competitive had to travel further to rinks like Tempe before returning back to the Jr. Coyotes.

“They were part of the Tier 1 Elite League so it was a lot of high level competition and tournaments,” Kastelic shares. “It seemed like every couple weeks you’re playing the top quality teams from Detroit and Chicago and being a part of that made a big impact on me to get me into junior.”

Whether it was his Canadian hockey bloodlines or not, Kastelic is very aware of how the Phoenix area influenced his hockey pathway.

“As a kid I idolized the Coyotes,” he mentions. “For kids growing up having a team in Arizona meant a lot to us to have players right there that we could look up to.”

Kastelic was drafted by the Ottawa Senators in the 5th round, 125th overall in the 2019 NHL Entry Draft.

Jaden Lipinksi was a 4th rounder to the Calgary Flames in 2023.

“I remember learning to skate at the Ice Den at a public skate when I was like 5 years old,” Lipinski recalls. “The Ice Den in those days was almost like an arcade but it was really the Coyotes that attracted me to the game, having big names around hockey-wise. It was pretty easy to take inspiration from that.”

Perception is an interesting avenue to go down when you talk about players coming from a place that many North Americans would assume couldn’t keep a surface frozen.

“When I got to Vancouver as a junior we had two guys from the Jr. Coyotes on that team in Vancouver, so they must have thought it was pretty good,” Lipinksi believes.

“Perception has changed a lot. We used to go to the Rocky Mountain Districts and would be questioned regularly how we can even play hockey there,” Kristy Aguirre, President of the Coyotes Amateur Hockey Association, admits. “We are getting more and more recognition nationally and our program has a lot to do with that. Outsiders don’t think it’s real – but it definitely is, and our footprint is getting bigger and bigger.”

“It’s what keeps me motivated,” DeAngelis says. “It’s the naysayers that say if you want to play more than youth hockey you have to leave Southwestern USA and go back east or a cold climate to develop. What Dallas, Los Angeles, Anaheim, and the Florida markets are doing is showing these markets work and kids can really develop staying home and sleeping in their own beds as long as they possibly can.”

Long before kids started walking through the doors of the Ice Den with a stick in their hand the facility has something else that is already nationally recognized.

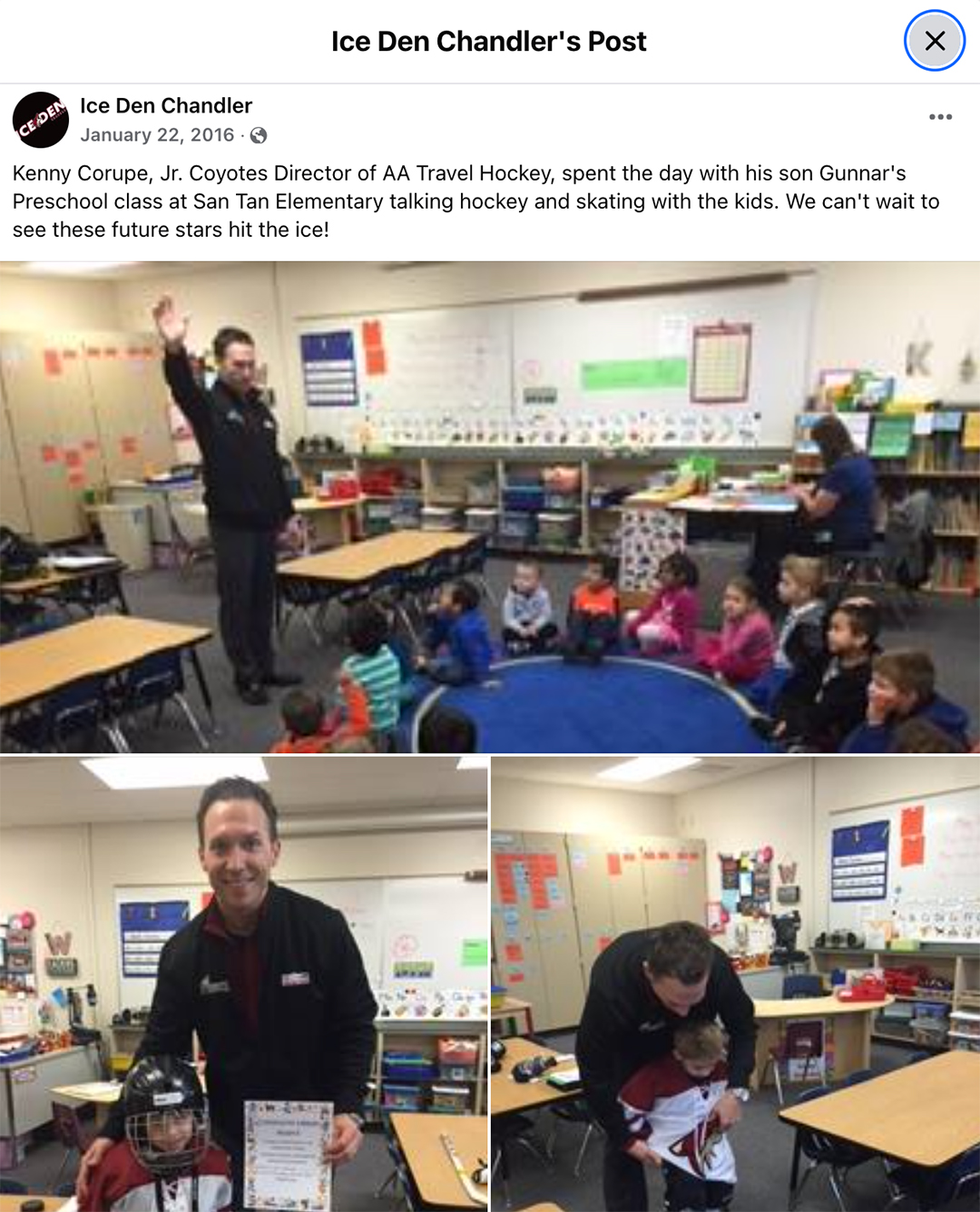

“We have one of the best learn to skate programs in North America,” DeAngelis boasts. “The figure skating club runs the program and they get awards for it every year. Once we get them skating at 7 or 8 years old, they will start working with Kenny Corupe and he is so valuable to our program.”

================================

Kenny Corupe deserves his own section in this story.

Of the previous Hockey Factories profiles we have done, I’m not sure I’ve had a more engaging and enlightening conversation about youth hockey than the one I had with Corupe.

“Kenny is going on almost 10 years with us, he is an amazing human,” Kristy Aguirre, Coyotes Amateur Hockey Association President, boasts. “He is well liked, well respected, the players love him – he’s ‘the guy’ when he walks in the rinks. He sets the tone for players and parents at such an important age group. Its guys like him who have helped our program to where it is today.”

Corupe played 15 years professionally, eight in North America. He got the coaching bug when part of his contract with his team in Italy was to help a different youth team regularly, ranging from U8 to U18.

Oh, and he had to do this in Italian – which he did not speak.

“I really found a joy in playing but also helping youth – whether that was a U8 or U18 player,” Corupe says. “I had knee surgery my last year in Norway and doing it after 15 years I knew what my body needed. So, I would skate and work myself around the arenas in Phoenix and started to get to know coaches and was approached by Mike about being a Hockey Director.”

“At that point I went to my wife, we had three kids at the time, and I said, “we’ve done this for 15 years, are you ready to stop?” Her response was: “Please!”

In January 2015 Corupe started with the club and was shocked right away how at the older levels kids in U16 and U18 did not know certain concepts and had bad habits. By that point those habits likely weren’t being broken.

His discovery after researching the program was that no one wanted to work with the younger kids.

When Mike O’Hearn, who ran the Ice Den at the time, approached Corupe and told him he could pick the team he wanted to coach, he told them right away he wanted to go younger.

“I went there because I could tell in our state there are a lot of hockey people here, but the coaches weren’t taking the time, in my opinion, to start at the beginning and build that foundation.”

Most kids enjoy hockey when they first sign up. When they get to Corupe, he has a big message at the beginning of the season.

“I know coming in you love the game but at the end of the year I want you to love it even more and you have the desire to come back and do more,” Corupe preaches. “I always roll back to two C’s – I want you to be confident and I want you to be creative. You can’t teach creativity, but I want to create an environment where the players can be confident enough to try things.”

Corupe coaches U8 and U14 within the Jr. Coyotes program and does so intentionally.

The contrast, he says, is where he gets the biggest reward.

“Just because you’ve got different ages you can’t forget to tap into their brains that they are still kids and find a way to motivate them to want to do whatever you’re asking, as a kid,” Corupe states. “At all levels there are times I’m yelling in the locker room – win or lose – but I try to leave it there so when you walk away from it you’re still a kid.”

Corupe was raised in Ontario and knows all about the pressures of youth hockey, external and internal. He sees his role as someone who reminds everyone around him that hockey is fun at any age and level.

“With my U8 team, I get them for 3 hours a week. I try to spend a lot of time off the ice in the locker room or in the hallways trying to connect with the kids and bonding and putting a smile on their face,” Corupe explains.

Corupe is extremely observant in the way he speaks about his players, one of the most enjoyable parts of the conversation is how very rarely X's and O's get mentioned, if at all.

It’s much more human and holistic.

“When I notice a player struggling, I’ve got to find a way to relax,” Corupe points out. “You have to watch that kid more intently, he made a nice pass on the next shift, so when he comes to the bench, I’ll pull him to the side, get eye to eye with him and told him "when you had that desire to go in and make that pass, I absolutely loved everything about that". He literally lifts up. Next shift, he’s flying.”

Having that contrast of U8 and U14 also helps being able to connect the dots in between and learning how to have an age-appropriate conversation with both players and parents.

“I use an analogy with our coaches that when you are on the bench, look at the back of everyone’s helmet. Every single one of those helmets are different, so I want you to think ‘"his is #10, how do they tick? This is #12, how do they tick?" I think it’s extremely important that every kid learns from a different whistle."

Brendan Shaw is one of those whistles.

Shaw has an extended history with the Jr. Coyotes, joining the club in 2004, but a long history in the game. He jokes you don’t see the impact you have on a 16–17-year-old at the time but now that some of his players are in their 40s, it’s something that energizes him as a coach.

“I’m in the start up world and I look at every team I coach like a start up,” Shaw opens. “My thinking is just "we have this business and there are 17-20 kids who run it and we have nine months to do it and how do we do it?"”

Shaw serves as the U12 head coach within the program.

“It was a lot of acclamation coaching a younger group this year,” Shaw concedes. “I want to create the same experience because I’m not going to dumb it down and I’m trying to evaluate myself at the same time, constantly checking how much I’ve done, how much can I do, when is too much or not enough and then you try to hit those milestones as you go.”

Shaw does that with a regular assessment of himself and the team, testing what they know and what they don’t know.

His biggest tell-tale signs are through his drills.

“I’ll do a drill with them I’ve done for 15 years and they can’t do it, and that’s fine. That shows me where they are and I can add or subtract from that drill to make it work,” Shaw explains. “It’s ok for coaches to say, ‘this drill isn’t working today’, look at it and say it’s not a bad drill, it’s just a bad drill for today and it doesn’t work. We don’t have unlimited ice time, and you have to be massively efficient as to what they know and some of that might be doing a drill they’ve seen 20 times but you don’t have time to sit at the board.”

The important part of drills for a coach, Shaw says, is not quantity, it’s quality and familiarity.

“I always tell people you want to get to 30 drills that the kids know by memory that I can just write on the board – not even drawing them out, just writing the name,” Shaw suggests. “The players know we are going to do this, this, and this for 20 minutes and then we are going to split up and go to team stuff, so it’s very structured and that way the onus is on the player, but you can’t expect them to know something they’ve never seen before.”

He acknowledges that even in his age group there are questions about what is next for the players and families.

Shaw, like Corupe, sees the big picture as the younger kids go through his age group.

“You only get 12 years of this. There are a lot of people on the flip side that say I missed out on so many things because I was so worried about what was next and they forgot about the moment,” Shaw recollects. “You hear that in January when they start talking about coaches and such for next season when we still have three months left. Live in the moment, the kid is going to be 18 soon, they are going to be gone and you’re going to be left there thinking ‘wow, this went so fast.’”

That’s where Corupe and Shaw both talk about as much as they are coaching the players, they have to coach the parents.

“I try to give them a story of ‘your kid played great today,'” Corupe will advise. “In two nights, when you’re putting the kid to bed, tell them you talked to their coach and he said he loved the way you backchecked or something like that. They are going to have a parent that loves them, tell them something positive about a coach that likes them and now they are going to bed with all this positive stuff and they'll forget about all the other bad stuff.”

================================

There are a lot of reasons why you would assume the weather in Arizona is not conducive to operating a hockey program, but there is also a big reason why the weather works more in favour for the Jr. Coyotes program than perhaps anywhere in North America.

No one is going to complain about nearly 70 degree weather in January.

As you would imagine, Arizona has always been a destination for people looking to get out of the cold during the winter.

The state has also been referred to as the retirement home for the NHL.

Luckily for Mike DeAngelis and the Jr. Coyotes, these players want to give back.

“A lot of NHL guys still live here. They have kids, they have families, and so they come to the Jr. Coyotes,” DeAngelis admits. “We’ve been able to tap into that and some of these guys become coaches with us, which has a big impact on our program.”

Slugocki agrees.

“The coach’s room was a great place. I would sit in there sometimes two hours before my practice just to answer questions and share information,” he recalls. “The NHL guys that are around may not be the best coaches or even want to coach but they are knowledgeable and willing to answer questions. They are just great ambassadors to talk to the 9 or 10-year-old parents and telling them to calm down and follow the process.”

The Jr. Coyotes website reads like an NHL almanac with no less than 10 coaches who have served some time in the league as players.

Dallas Drake is one of them.

“I was involved in coaching in Traverse City for a couple of years but I had no connections in Arizona when we moved here,” Drake explains. “An opportunity came up to help finish off a year, so I offered to do that and it snowballed from there.”

Drake played over 1,000 NHL games with Detroit and St. Louis. He was also part of the Winnipeg Jets move to Phoenix, spending time with both clubs.

He is now the head coach for the U18 Jr. Coyotes team.

“It seems like all the kids these days have really good skill sets, they can all skate, they can all handle the puck,” Drake details his first thoughts when joining the organization. “When I get them in the U16's and U18's, it’s trying to develop their awareness and hockey sense. Kids these days watch so much video, it’s not always the right video, but it is a great tool to help these kids with a lot of facets of their game.”

The video aspect is something we spoke a lot about, asking him how much video he was using as a player and where analytics would fit into his game.

“Video is very important because what I see is very different from what the kids see, and I always try to explain that to them,” Drake mentions. “It’s important for kids to watch that back and see it directly, kids are all about social media now and they like watching themselves. Sometimes I wish they would sit down and watch an entire NHL game or a Division 1 game, not just clips of it because I think in a lot of ways that helps them as well.”

When it comes to his on-ice practices, Drake is strong on repetition – whether it’s a skill or a drill or combining them all together.

“I really like the amount of times we are on the ice practicing, they have the option of practicing 5 days a week, which was really big for me,” Drake continues. “I think that’s where kids learn and you can break things down for kids, especially when it comes to breaking them down to what they need to play at the next level since this is really the important years to push for that.”

Having NHL veterans like Drake, Shane Doan, Steve Sullivan (who coached in the program for eight years after his retirement and recently became the AHL’s Toronto Marlies’ head coach). Michael Grabner, Derek Morris, and others are invaluable, not just for the validity of the program but also to explain to players and parents what a hockey journey can look like.

Mike DeAngelis and his group call it “The Pathway.”

Because everyone can dream one day about playing in the NHL, but for a community of parents who had never been involved in the sport before – no one knew how to get there.

================================

“It’s unravelling the web of what the industry of hockey is,” DeAngelis explains. “It’s one of the most difficult webs to explain the directions you can go and if one direction is better than the other for each kid.”

Without really giving it much thought before, DeAngelis brings up a great point in his delivery to parents because there is one aspect of this sport no other has – junior hockey.

“This is the only sport you don’t go from high school to college and it’s complicated when you are explaining the WHL or the USHL and trying to get the most exposure,” DeAngelis comments. “We do presentations and things to the parent group and try to make it as simple as we can to say ‘this is the path, these are some options if you are good enough’ but it’s going to get blown up again with the new NCAA/CHL ruling.”

Drake’s insight is similar and at the forefront with his team’s age group.

“It’s difficult to give parents an answer because everyone develops at such a different rate,” Drake admits. “Everyone is so concerned about getting to the junior level as quick as they can but for a lot of them, they aren’t ready to do that. If you are jumping to junior and playing 4 or 5 minutes a night, it’s hard to say you’re getting better. I tell parents to take a breath. If they don’t trust the process and they try to play somewhere they can’t play and then they don’t play and they put themselves in a worse spot and lose an entire year.”

Kastelic went the WHL route with the Calgary Hitmen, admitting it’s not the first route most people in the Southwest US go, but drew that from his Canadian background.

Jaden Lipinski followed suit, playing parts of three seasons with the Vancouver Giants.

Shaw understands that as a coach and a father.

“I’m always talking to kids who are even out of the program now that are in the USHL or WHL about that journey,” he mentions. “I talk to kids who are 14 years old who say they are going to go to the WHL because they haven’t heard from any colleges and I have to tell them, they don’t talk to 14-year-olds. They have to understand the road map.”

Educating families on every step of the journey is crucial to keeping them invested and aware of what’s to come for their child.

Because the journey is long for players.

And for parents everywhere, especially Arizona, it’s also really expensive.

================================

“It truly bothers me how expensive it is,” Corupe states clearly.

“I see behind the scenes where the money goes – everything goes up. In Arizona when you’re paying $400-$500 an hour for the ice. It’s crazy.”

When doing introductory meetings, DeAngelis talks about building the foundation for the love of the game because it does not come as naturally in that area as it does in other parts of the country.”

“But the other important thing we have to do is not scare them away from hockey because, as the kid gets older and starts playing travel hockey in Arizona, there is something scary that is about to happen – and that is the cost of playing travel hockey in Arizona,” he admits. ”There are not a lot of places that are driveable from here, other than maybe Vegas and California. But when the 10 year olds want to go to Detroit for a tournament, it’s an expensive undertaking.”

Simple geography makes it a clearer picture.

“We are two hours from the Mexican border, that’s one way to look at where we are,” DeAngelis details. “The cost of playing hockey is a shock to a lot of people who don’t have a connection to the northern provinces or the northern states.”

“We travel every two weeks, we come home for a week and a half and then we travel again,” Drake shares his U18 schedule. “Every 10 days we are on a plane, and they are long flights and you’ve got to consider the school time that kids are missing – there are a lot of factors minus the cost and the cost is a big part of it.”

Shaw begins to use his playing time as a comparison to what happens in the state now.

“I flew twice as an amateur to the national tournament, there’s no flying in the USHL and we flew once a year in college hockey. So, that’s six flights by the time I’m 24. Some of these kids are doing that by the time they are eight.”

Arizona does host the Tier 1 Elite Tournament in the state and are starting to draw a number of other bigger tournaments, but outside of that area there is not much. Most big tournaments are moved around the USA but, by that, I mean Chicago, Detroit, Dallas, Boston and anywhere that is not the US Southwest.

As state president, Shaw was part of launching the AZYHL, a league that not only benefits families with games, but saves money.

“The biggest thing is what we can’t fully fix – we are out in the middle of nowhere compared to other programs,” Shaw engages. “We can’t just go down the street and find a bunch of competition. We have our area, which is about 15 sheets of ice, but once you get outside there you’re talking about a four hour drive. That’s the difference.”

The challenge has always been having enough high level talent locally so these trips do not have to happen.

“I’m a firm believer that you get what you pay for,” Aguirre mentions. “Our program fees are comparable to others at our level and I think people realize the coaches, facility, staff are all outstanding here. Scottsdale is a bit of a different city, it’s a different clientele because it’s a fairly affluent area but we are trying to do everything we can to offset it as much as we can but not having anyone here – we have to travel.”

The Jr. Coyotes program is unique, compared to others around the country because of its depth. Not only is there the AAA program, but the umbrella also covers AA and house league.

Having that many options for a family is something DeAngelis is proud of.

“If you want to play hockey recreationally, you can and we have that. If you want more than that, we have that too,” DeAngelis will tell families. “We have the AAA travel program and we also have a number of development programs right below it so in that program it doesn’t cost as much, they don’t have to travel as much to find the competition and play locally.”

Corupe has a suggestion, starting from the beginning.

“If we collectively, as a state, work more with our younger kids, there are a lot of hockey players here and I believe we need to have better coaches for younger players to expand it more so our older kids don’t have to travel as much,” Corupe says.

"There’s nothing worse than me having to have a conversation with a parent who says their kid can’t play anymore because it’s costing too much money, that’s a shame,” he continues. “I can’t argue if a kid wants to go play soccer and it costs them $1,000 for the year to play. It’s hard.”

================================

The intention of this feature was not just to highlight the great program that is the Jr. Coyotes but to also shine a positive light on hockey in Arizona.

But there is no point avoiding the white elephant in the room.

The NHL is gone.

So what does that mean for hockey, in general, in the state? I let the experts explain.

Brendan Shaw: "Everyone wants to get into the fact that the Coyotes left and how are we going to handle that now. We are stronger now because that development of the west has made hockey better. It’s raised the level of hockey as a whole and the game needs that.”

Jaden Lipinski: "It was a weird ending at Mullett Arena, it’s going to be weird without them. The Coyotes had a big impact on our lives, without them I’d probably be playing baseball. The game of hockey has brought me to some really great places. We need to figure out how to keep it there."

Mark Kastelic: "I think there’s definitely a market there, so I hope they figure out the logistics and make it work. You could see how excited the city was when the Coyotes were having their playoff runs. Having that team for me growing up was something I cherished and if they can get everything figured out that would be awesome for the area."

Kenny Corupe: "I think another NHL team would absolutely fly here. I’ve lived in so many markets and I can tell you this area could absolutely support it if it is done right."

But we leave the final word to the one who has lived Arizona hockey his whole life.

As I ask the question if the game is sustainable in the desert, Slugocki admits to feeling a wave of emotions as he begins to speak.

His passion is unwavering.

“Hockey in Arizona has given me everything in my life,” Slugocki begins whole-heartedly. “I’ve been on the ice since I was 2-3 years old. It’s all I’ve ever known. I would have never thought I could have a career in hockey and now I get to work with some of the best players in the world because of the Jr. Coyotes and hockey in Arizona in general. It means the world to me. It was crushing for a lot of reasons when the Coyotes left. I know there’s a chance my kids won’t get the same rush of going to a game like I did with my Dad when I was 5 or 6 years old. I have a lot of great memories that have helped shape me. You won’t find a bigger supporter of Arizona hockey than me.”

The Utah Hockey Club's journey started on October 8th, 2024, defeating the Chicago Blackhawks in their regular season opener.

I don’t know if many Phoenix-area TVs were tuned to that game.

But hockey still lives in the desert. The game continues to grow, the list of names, like Auston Matthews, Matthew Knies, Josh Doan and Mark Kastelic gets longer and longer.

In the Valley of the Sun, the sun continues to shine on Arizona hockey.