Many figure skaters are unqualified to be hockey skating coaches.

Power skating is a misunderstood form of performance enhancement.

Many skating coaches have no formal education in movement sciences, no certification to be a skating coach, and many coaches transition from being a figure skater to working with hockey players.

“Power skating” has been adapted from figure skaters. Many figure skaters are unqualified to be hockey skating coaches. Moreover, there are many misconceptions about the skills and drills used by power skating instructors.

Origin of power skating

Some say Laura Stamm was the first power skating instructor. In the 1970’s and 1980’s she worked with New York Islanders players in an attempt to improve their skating performance.

Power skating originated from figure skating. Power skating uses figure skating techniques and “tricks” in an attempt to improve the skating performance of hockey players. We still see power skating instructors using what used be called “compulsory figures” from figure skating.

Before 1991, high-level figure skaters had two components to their figure skating performance:

2. Freestyle skating

Compulsory figures have morphed into “edge work” for hockey players.

Efficacy of figure skaters being skating coaches for hockey players

An analogy to use when talking about figure skaters being skating coaches, specifically figure skaters being hired by NHL teams, is comparing the qualifications needed by skating coaches to those needed by strength and conditioning coaches.

Many NHL strength and conditioning coaches start their career as a graduate assistant or intern for a college athletic program. All NHL conditioning coaches must have an undergraduate degree. Most conditioning coaches are certified (certified strength and conditioning specialist through the National Strength and Conditioning Association), and they have years of experience working with athletes before being hired by an NHL team. NHL skating coaches do not need a degree in any of the movement sciences such as kinesiology, biomechanics, and/or exercise science. Moreover, skating coaches do not need skating coach training nor do they need any certifications.

It appears the primary qualification figure skaters have to work with NHL players is that they were a competitive figure skater.

Testimony to the lack of knowledge figure skaters have about how hockey players skate is that they speak in general terms when discussing what a player needs for skating improvement. Rarely do we hear figure skaters/power skating coaches discuss the objective characteristics that make players fast.

“You can’t just go from figure skating and jump in and become a great skating coach in hockey. There’s a process to it,” figure skater turned power skating coach Dawn Braid explained in an interview with Sportsnet. “We skate differently — there’s pieces to the foundation that are the same and pieces that are different. And I think, like any job, you need to do your work, you need to study it.”

Hockey players do not want to skate like a figure skater. We have known the foundation of hockey skating for 45 years. Likewise, we have known the characteristics of fast hockey players for the same length of time.

All fast hockey players skate with the same characteristics:

- Wide stride.

- Quick recovery, the recovery skate does not recover under the mid-line of the body.

- The recovery skate lands under the shoulder so that the skate can get on the inside edge as quickly as possible to start the next push-off.

- Deep knee bend (approximately 90-100 degrees of flexion) just before push-off.

- The upper body has significant forward lean the faster a player skates.

- The arms move side-to-side in equal and opposite action-reaction to the movement of the legs (legs push to the side therefore the arms must move side-to-side – Newton’s second law of physics – for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction).

Watch Connor McDavid to see his skating characteristics check out his arm movement side-to-side, his wide stride, and his quick recovery:

Mat Barzal has a wide stride, quick recovery, and recovery skates landing under his shoulders:

Kendall Coyne Schofield skates with her arms moving side-to-side, a wide stride, and quick recovery:

Misconceptions about how to teach skating

The most common misconceptions about skating that power skating instructors teach include:

- Arms move forward-backward because that is the direction of travel.

- Use a long recovery like a speed skater to get a longer push-off. This is wrong because the skates cannot start to push-off until the skate is under the shoulder, and on the inside edge.

- Keep the body upright. This is how a figure skater skates. A hockey player would never skate like this because they must lean forward to skate faster and be ready for body contact.

- Gliding on one-skate will enhance balance on two-skates. One power skating instructor indicates: “If you can’t stand on one leg you cannot be a good skater. So, single leg stability is the number one thing,” (Marc Power, power skating consultant). This quote is testimony to the limited understanding many skating coaches have about how hockey players’ skate. A skating coach must be dramatically hidebound to think that single leg stability is the “number one thing.”

- Hockey players rarely glide on one-skate. In a study we did to investigate the skating characteristics of NHL forwards, we analyzed 25 second periods and never observed a player gliding on one-skate. Even when skating at slow speed, the average amount of time spent on one skate is 0.43 seconds.

Common drills used in power skating

Many power skating coaches use skills and drills that make players move completely different than how they skate in a game. One of the first rules of teaching or coaching is that we must practice as close to the way we play. Therefore, drills such as extending gliding on one-skate are contrary to the way players skate in a game. The specific misconception is that gliding on one-skate will help gliding on two skates, which is wrong.

The use of “compulsory figures” type of skating is commonly used, especially by figure skaters. This is contradictory to the way players skate during a game because game-performance skating is characterized by striding, gliding on two skates, gliding and cross-over turns, acceleration, and body contact repeated during the shift.

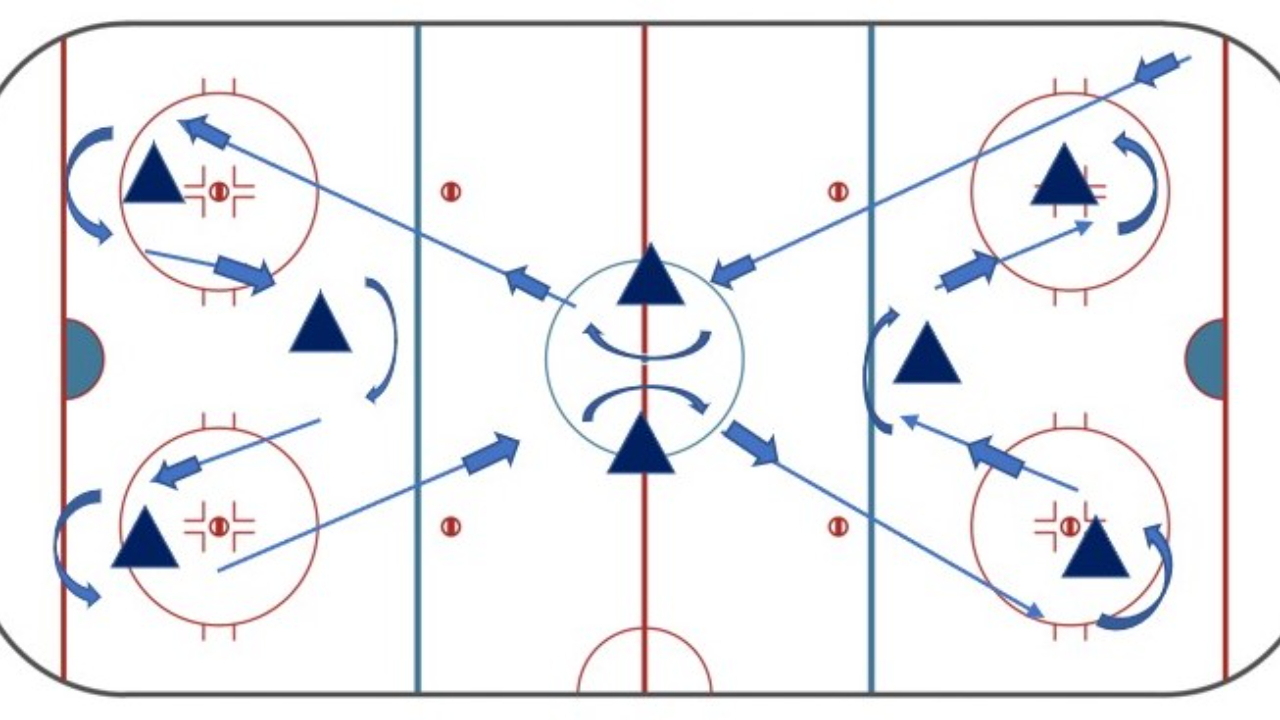

Finally, many power skating coaches will have players line-up at the ends of the rink to perform the skating drills. There is a problem with this type of coaching, the players get very little time-on-task to improve their skating performance. An example of this is a time-motion analysis the author did as a consultant at a summer hockey school.

Ten power skating sessions were observed and analyzed for a time-motion analysis of how much time the players were actually doing drills.

The results are as follows:

- Average length of the power skating session = 70 minutes

- Time players spent standing in line = 50 minutes

- Time of unproductive movement (moving forward in line) = 10 minutes

- Time performing the drill/skill = 10 minutes

- Average time the players were doing a drill = 6 seconds, which is not enough time for the muscles to memorize new and better movements.

This is the reason power skating must be reevaluated as a legitimate form of performance enhancement for hockey players.