Representative Learning Design

Representative learning design is as the name suggests. It is a design principle used to create learning environments (i.e. practices) that represent the elements of the game. In a representative learning design, players are exposed to all the same elements, decisions, problem solving and chaos that the game would provide. This does not mean that RLD is only about playing games in practice. True, small area games do provide a representativeness of the game. But in a RLD, activities need to only feel like the game, they don’t need to look like the game.

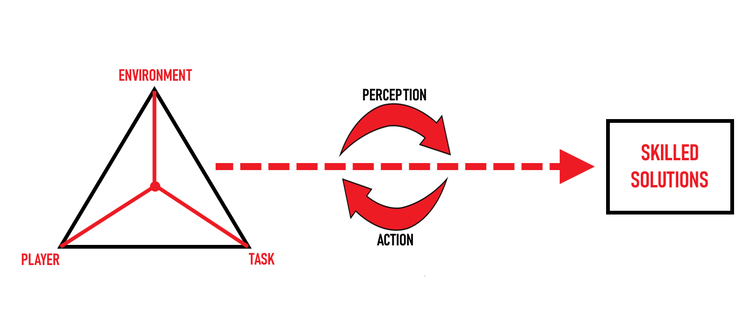

RLD is the first design principle we look at that addresses all three of the core principles of Ecological Dynamics.

· Skill emerges from interacting constraints within the environment, the task, and the player.

o RLD results in practice activities where all three of these constraint types will be present.

· Skill development is non-linear.

o Motor learning is predominantly non-linear. In linear learning we see structured progression (A before B, B before C, etc.), fixed content (i.e. the same for everybody) and limited flexibility. Liner learning is often associated with the search for the one ideal movement solution.

RLD offers flexible exploration, self directed learning, unstructured progressions, and content that can be viewed as different for each player.

· Skill emerges from a continuous process of perception-action coupling.

o In a RLD players will be exposed to activities that require them to collect information, assess that information and make decisions to act on that information. Actions will be coupled to the player’s perceptions.

It is the fact that RLD addresses all three core ecological dynamics principles that creates such value for coaches. As important as Session Intention and Constrain to Afford are as environmental design principles, I believe representative learning design is the “foundational” principle that brings Ecological Dynamics to life and ties everything together for skill development.

What do RLD activites look like? Lets watch this video...

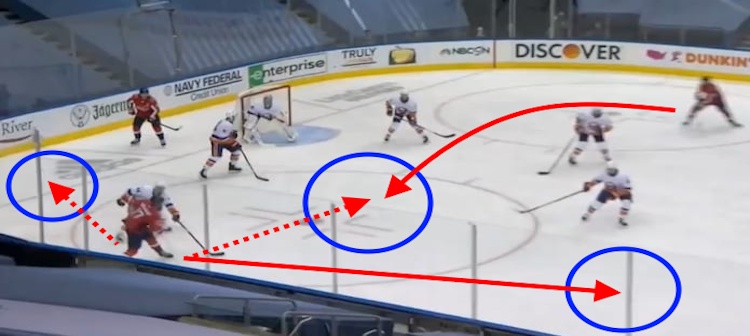

We can see a variety of game representative elements in this setup, as well as some task constraints.

The puck carrier must first "cut the hands" of the defender obstacle and protect the puck along the wall. Somewhat representative. Then a real defender engages and they have to deal with the reality of pressure on the wall. Fully representative. A defenseman activates off the blueline and dives into the scoring zone looking for a pass. Puck carrier has to find that player and make the pass under pressure. Fully representative.

Inside this representativeness and constrained environment the coach would now be assessing to determine next steps:

1. Remove the net (i.e. the defender obstacle) and have the defending player engage right away making it even more representative.

2. Manipulate the level of pressure (passive to full).

3. Place a second defender to pick up the defensman activating off the blueline.

4. Manipulate constraints to afford solutions the players are not finding.

5. ???

Benefits of a Representative Learning Design

The development of techniques such as skating, passing, shooting, and puck control do not require environments and activities that represent the game. Players do not need to be exposed to real game like scenarios or real elements of the game to learn how to make a saucer pass or refine the saucer pass technique they currently possess. Technical development can be easily, and in many cases well done, using isolated, non-representative activities.

But we are discussing more then technical development in this series. We are looking at skill development. And as we saw in part 1, skill is a decision-making, problem-solving quality that exists in the game context. Skill cannot exist outside the game context. Technique can. Therefore, from a skill development perspective, we must use design approaches that place players in game context over isolation and non-representative activities.

Representative learning design is game context. As we said earlier, it does not always have to look like the game, but it must feel like the game. What does that mean? It means that elements of the game that require a player to think, perceive, decide, act on perceptions, apply their techniques, etc. will be and must be present. Can these elements of the game be present in activities that do not look like the game? Well, lets consider a low organized game like puck tag.

All the players skate around with a puck between the bluelines. One player is designated the chaser to start the game. That player must skate around controlling their puck while trying to force another player to lose possession of their puck. When they do that, that player quickly regains possession of their puck and then becomes the new chaser.

In this game players must find space, protect the puck, transport a puck in traffic, have vision, scan the ice, elude pressure, extend possession. These are all real elements of the game. But the activity looks nothing like the game. It only feels like the game.

There is much to gain from a RLD. Here are some of the more critical benefits:

1. Skill Development

This benefit has been addressed but let’s start with it as this is the essence of our discussion. Developing skilled players moves well beyond isolated, technical development. We cannot address skill development without providing our players game context. It is the consistent exposure to representations of the game that allows players to develop their abilities to perceive and act using the technique they possess.

2. Practice to Game Transfer

If we want players to perform within the game, then they must train within the game context. Practice and training sessions must present them with the real elements of the game so they can develop solutions that transfer. This is not to say that they learn solutions by memory and then pull them out of their tool bag when required in the game. What a RLD provides, when combined with a CLA, is an approach that allows players to learn how to find solutions. That ability then transfers to the game allowing players to perceive all the same elements and recurring scenarios and find solutions. Those solutions may or may not be the same solutions they found in practice. RLD + CLA = the development of solution creators.

3. Perception-Action Coupling

All actions are based on a player's perceptions. That perception may be limited or in depth but suffice it to say that when a player acts they do so based on something they see, hear or feel. And as we learned earlier, in Ecological Dynamics and the CLA that action is considered an expression of skill. In a RLD, activities are rich with perception-action possibilities. They feel like the game or look like the game. Players will be asked to look around, collect information and act accordingly. Its inherent in a RLD. But beyond this inherent quality a RLD provides one other benefit. It keeps perception and action coupled. In isolated drills, actions are decoupled from perception. Isolated activites are devoid of perception. Players are told exactly what to do and how and they follow that pattern on repeat. Perception gets removed.

Skill development is reliant on a player acting based on their perceptions. In hockey terms, we want them "reading and reacting". When you decouple actions from perception you lose skill development and fall back into the realm of technical instruction.

Before we leave this concept/benefit we should point out that not only do players perceive in order to act but they also act in order to perceive. When we talk about the notion of read and react we never speak of react and read. But skillful players do this all the time. They perceive the environment around them, they do not see a viable solution so they move again. That movement changes the environment and provides them new perceptions. Game representative activities within a RLD will "force" players into this constant cycle of perceive - act and act - perceive. Actions and perceptions remain coupled at all times.

Lastly, as coaches we must also understand that perception is embodied. This means that players only perceive what their current skill level and abilities allow them to perceive. A player that cannot make a saucer pass will never perceive, or see, the opportunities to make a saucer pass. A player that can only change shot angle with a toe drag will not perceive the opportunity to push to the inside and change the shot angle.

4. External Focus of Attention

Activites that are representative of the game, as opposed to isolated activities, are more inclined to provide an external focus of attention for the player. An external focus of attention is simply a focus on the environment and the interacting constraints within it. External focus of attention is geared more toward the achieving of outcomes and objectives, and solutions within the environment which equates to skill development. Internal focus of attention is a focus on the self. Players executing isolated activities to develop technical abilities are typically focusing internally. What are my feet doing? Am I controlling the puck properly? Which direction do I go around the cones?

5. Technical Development

This one can often be difficult for coaches to accept. But the reality is that even within a RLD, players will develop and improve their technical abilities of skating, passing, shooting, puck control, checking. Research has shown that the use of a technical, isolated model versus a RLD model does not provide any greater gains in technical competency over time. This is not to say that technical development is not to be used or serves no value. But it is important to know that gains can be achieved working in a RLD.

To quote Barry Smith from the Glass and Out podcast…” We can help you by replicating the game in practice…If we want to improve…lets practice chaos.” This is the essence of representative learning design.

Working in a Representative Learning Design

The common question I get from coaches when discussing the use of a RLD is “how are they supposed to learn the fundamentals before being placed in game context drills?” This is a fair question. We have something unique in our sport that very few other sports have…our athletes must navigate on thin blades of steel. But in benefit #4 above I point out that with a RLD the technical development of those “fundamentals” can be achieved. But what if it is not? What if some players lack a technical proficiency and the game context activity is just not addressing it?

This is where we come back around to the Constraint Led Approach, and something referred to as task simplification.

As impactful and valuable as RLD is I would be remise if I did not draw out the full impact of combining it with a CLA. RLD provides us the game context and game elements, the CLA provides us the teaching methodology to manipulate and facilitate learning. And it is through using a CLA that we can address when and how to move to technical development.

In a linear model of development, a coach would start with technical drilling. In the linear philosophy players must learn techniques before they can proceed to game context where those techniques are needed. Linear approaches would not support the game context as a place where the techniques can be developed, only used. In the non-linear philosophy of ecological dynamics, CLA and RLD, the coach can start with game context activities (at appropriate levels of complexity of course) and let the techniques develop as players find solutions. In many ways those solutions can be the use of a technique or the attempt to learn a new technique. However, there will be times when players are not developing the techniques they may require. They simply choose to use the ones they already possess over and over. And often they only choose to use the ones they feel they are best at executing.

We have two methods to address this issue:

· CLA – we now know that when using a CLA we can manipulate constraints, change constraints, add, or remove constraints to target learning intentions. Through this method the coach may be able to “draw out” an existing technique from players and afford them more opportunities to use it as a solution. The coach may also be able to create affordances for players to learn a new technique.

· Task Simplification – often a coach will jump away from a game context activity too quickly when there are issues in technical execution. Most often they move back to isolated technical drilling by decomposing the RLD activity down to its raw, technical components. Doing this removes the game elements. Task simplification is a process whereby you preserve the intention and some game elements of the activity, but you simplify it to allow players to use the techniques they require. Task simplification allows the coach a method to scale an activity down incrementally before moving all the way out to isolated drills. It is worth noting, that at some point task simplification may take you out of the RLD activity and into technical isolation, but you have now assessed that the players need the technical drill to prep them to come back into the activity rather then just jumping our prematurely.

Proponents of an ecological dynamics approach do not discount use of unopposed or isolated activities. When and how they are used is the more important question. When a coach does not get the results, they desire via a CLA or task simplification then maybe the use of an isolated, technical drill is required to establish a foundation quickly with the intent of getting players back into the RLD.

Part 5 - Repetition Without Repetition

References

- Renshaw, I., Davids, K., Newcombe, D., Roberts, W. (2019). The Constraints Led Approach: Principles for Sports Coaching and Practice Design. London: Routledge

- Gray, R. (2021). How we Learn to Move: A Revolution in the Way we Coach and Practice Sports Skills. United States: Perception Action Consulting & Education LLC

- Gray, R. (2022). Learning to Optimize Movement: Harnessing the Power of the Athlete-Environment Relationship. United States: Perception Action Consulting & Education LLC

- Chow, J.Y., Davids, K., Button, C., Renshaw, I. (2016). Non-Linear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction. London: Routledge

- Attri, R.K. (2018). The Models of Skill Acquisition and Expertise Development. Singapore: Speed to Proficiency Research

- Nash, C. (2022). Practical Sports Coaching 2nd Edition. London: Routledge

- Button, C., Seifert, L., Chow, J.Y., Araujo, D., Davids, K. (2020). Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: An Ecological Approach.