They've developed four NHL first-round picks in the last three years.

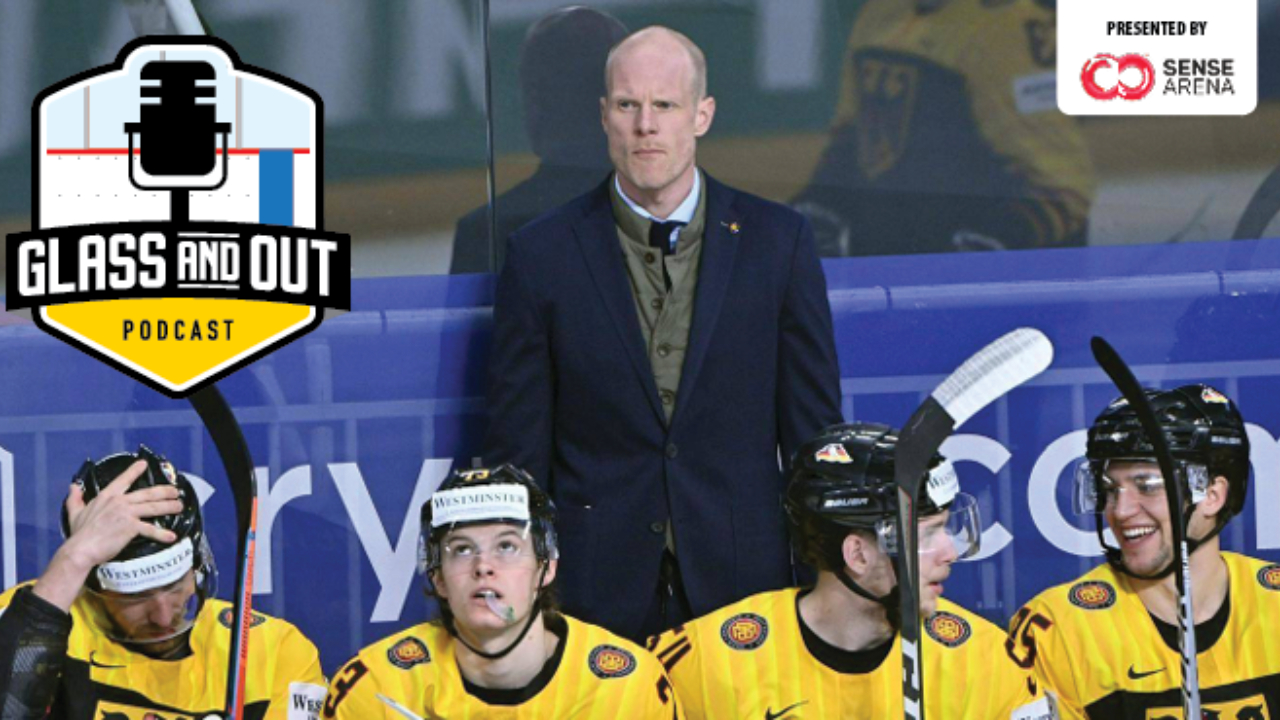

Had I told you in 2017 that Germany would win an Olympic silver medal, have an Art Ross, Ted Lindsay and Hart Trophy winner, and develop four NHL first-round draft picks within the next three years, you would’ve said I’m full of it. Yet, that is exactly what happened.

Team Germany beat Sweden and Canada en route to Olympic silver in 2018. Dominik Bokk was drafted in the first round of the NHL draft in the same year, followed by Moritz Seider in 2019 as well as Tim Stützle and Lukas Reichel in 2020. And Leon Draisaitl is the NHL’s latest top scorer and MVP.

But while there’s certainly more to it than luck, the road ahead remains a challenging one for German hockey.

To get a better understanding of the current situation, let’s go back to the 2014-15 season.

Draisaitl had just become the first German first-round draft pick in 13 years. Becoming a third-overall selection by the Edmonton Oilers was an impressive feat. But Draisaitl was an outlier. He was only the fifth first-rounder in German history, the only drafted German in 2014, and to get there, he chose to leave the Adler Mannheim junior system to develop in the WHL.

What’s more, there was virtually nobody in the pipeline to replicate Draisaitl’s success. The German U20 and U18 teams were relegated from their respective world championship top division, the men’s team eliminated in the preliminary round. There wasn’t a single U18 player in the DEL, and only nine U20 players appeared in more than 10 games that season.

Something had to change. And thus “POWERPLAY26” was born.

POWERPLAY26 is a program developed by the Deutscher Eishockey-Bund (DEB), Germany’s ice hockey federation, that aims to reach an ambitious goal by 2026: to be a consistent medal contender at world championships and Olympic tournaments.

To get there, the DEB came up with several key elements, including:

- A centralized coaching structure focused on developing high-quality coaches who can, in turn, offer the same level of development to players across all clubs.

- Introduction of full-time national team coaches ensuring year-round player development by being available as mentors, organizing frequent development camps, etc.

- Introduction of no-contact hockey below the U14 level to focus on skill development and a strong focus on practice over game action.

- Introduction of a certification program that results in financial penalties for clubs that don’t reach predetermined standards – e.g. adequate levels of ice time per week and a large number of junior coaches – but also rewards those that do.

- A steady increase in the number of U23 players required in DEL lineups each game (two for the 2019-20 season) and on the roster (six by 2026).

- Implementation of a “long-term player development” program for youth players, with a focus on didactic and technical elements along with improved quality assurance.

While the Olympic medal in 2018 was most likely a result of NHL players’ absence from the tournament, POWERPLAY26 is starting to show early results.

In the 2019-20 campaign, 22 U23 players made appearances for DEL teams, including five U18 players and nine who appeared in 10 or more games. Compared to their European competition, it feels like nothing – 164 U23 players appeared in SHL games last season, including 25 U18 players. Compared to 2015 Germany, however, it’s a giant leap in the right direction.

Two clubs that are doing a particularly good job are Kölner Haie and Adler Mannheim. While the Haie failed to keep NHL first-round pick and current Carolina Hurricanes prospect Dominik Bokk in the system, 15 players on the 2019-20 roster were developed in their own junior program.

“We have a good concept to show players: ‘if you stay in the system, you’ll have the chance to play in the DEL or DEL2’,” says Rodion Pauels, long-time head coach and manager in Cologne’s junior and pro teams. “If a player wants to leave anyway, that’s no problem at all. But we don’t want to hide.”

Frank Fischöder, who spent 20 years coaching Mannheim’s junior teams – including Draisaitl, Seider and Stützle – has a similar take on the situation. “We can offer our players a lot of options and flexibility (U20 DNL, DEL2 and DEL). The current situation is very, very promising and I really hope the German route will prove to be a good one in the future. We want to become a serious alternative to North America.”

If Seider, Stützle, Reichel and 2020 second-round pick John-Jason Peterka are any indication, it’s working out extremely well.

Still, one crucial question remains: Is the current success sustainable?

The answer, unfortunately, appears to be no.

Ice hockey is still outside the top 10 most popular sports in Germany, both based on interest in the population and the number of registered athletes. As long as this is the case, the chances of developing high-end NHL talent remain low, and doing it consistently is highly unlikely. Plus, as the 2020 draft shows, depth is a real issue.

Case in point: Germany had three players picked in 2020, all within the first 23 selections. The upcoming 2021 class completely lacks NHL talent. Don’t be surprised if there isn’t a single German drafted next year.

Nevertheless, it’s easy to end on a positive note. The DEB has a concept. One that’s allowing more and more junior-aged players to jump up to the pro ranks. One that produces players with excellent skating and skill levels. And one that’s developed four NHL first-round picks in the past three years.

There are six years left to continue the positive development of POWERPLAY26. At the very least, there’s finally hope.