Should players be focused on aerobic or anaerobic conditioning?

Introduction

Specificity of training is the golden rule for athletes. The training an athlete does needs to be specific for the demands of the sport. One of the most important components of fitness for hockey is the ability to do high intensity work (during a shift) and recovery quickly (on the bench, or between a whistle and puck drop) to be ready for the next shift. The high intensity work on the ice is anaerobic in nature.

What is aerobic conditioning?

Aerobic conditioning is sometimes referred to as “long slow distance” training. Aerobic conditioning is characterized by medium intensity long distance exercise (30 – 90 minutes). A practical way to determine if an athlete is doing aerobic conditioning is if they can carry on a normal conversation while exercising. Specifically, aerobic training has a relatively low heart rate.

Aerobic conditioning also trains the muscles to contract slowly, for a long period of time. It trains, what are referred to as, slow twitch muscle fibers. These are muscles that contract slowly but can keep going for a long time. Aerobic training is essential for sports such as soccer, field hockey, long distance running, or any sport where the athlete must move for a long time at a low to medium intensity.

What is anaerobic conditioning?

Anaerobic conditioning is high intensity exercise done for relatively short periods of time (15-seconds – 2-minutes). By its very nature, anaerobic conditioning has to be done is short bursts, because an athlete cannot maintain high intensity work for a long period of time.

Anaerobic fitness is important for sports such as hockey, CrossFit, sprinting, baseball, football or any sport where an athlete must produce high levels of exertion for short periods of time. Moreover, anaerobic conditioning trains the muscles to contact powerfully and fast. It trains, what are referred to as, fast twitch muscle fibers. These are muscles that contract with a lot of force, they contract fast, and fatigue quickly. This is the type of conditioning hockey players need in order to have high levels of fitness for a game.

Percentages of aerobic and anaerobic physiology in hockey

The late David Montgomery Ph.D., formerly at McGill University, was one of the foremost authorities of hockey physiology. He wrote a paper entitled “Physiology of Hockey” in which he indicated anaerobic fitness contributes 69% of the work done during a game, and aerobic fitness contributed 31%, mostly during the recovery during shifts.

Howie Green, Ph.D., another preeminent hockey physiology expert, is quoted as saying “Hockey is uniquely stressful … the heat and humidity of the protective gear, the high level of coordination required, the repeated demands made on the muscles with little rest and the astounding requirement that it’s played while balancing on skate blades are all factors (in fatigue).” Dr. Green also suggests that hockey is stressful because there are upper body movements and contractions superimposed on lower body movements and muscle contractions.

Some people suggest that in order to have high levels of anaerobic fitness there must be a good aerobic foundation. Moreover, there are people that believe a high level of aerobic fitness can help recovery between shifts. There has been interesting research to disprove these ideas.

Mark Arnett, the author of a study published in 1996, found the recovery of male college hockey players was enhanced from pre-season to post-season after an entire hockey season which consisting of no aerobic training. The on-ice practices Arnett describes were high intensity short duration type training. Recovery from high intensity on-ice work may be best accomplished by performing interval training during the off-season.

The author, and a colleague, Tina Geithner, Ph.D., conducted research with the University of Alberta women’s hockey team. We wanted to investigate if the players who performed well on a cardiovascular endurance test (Beep Test) had the best time and quickest recovery when doing an on-ice anaerobic skating test. We found the players who did well on the Beep Test, did not always perform best on the anaerobic skating test, and did not necessarily recovery quicker.

Other hockey physiologists have found the same thing. They have found that aerobic conditioning trains the long slow distance “system” and anaerobic conditioning prepares an athlete for high intensity work and a quick recovery.

What is best for conditioning for hockey?

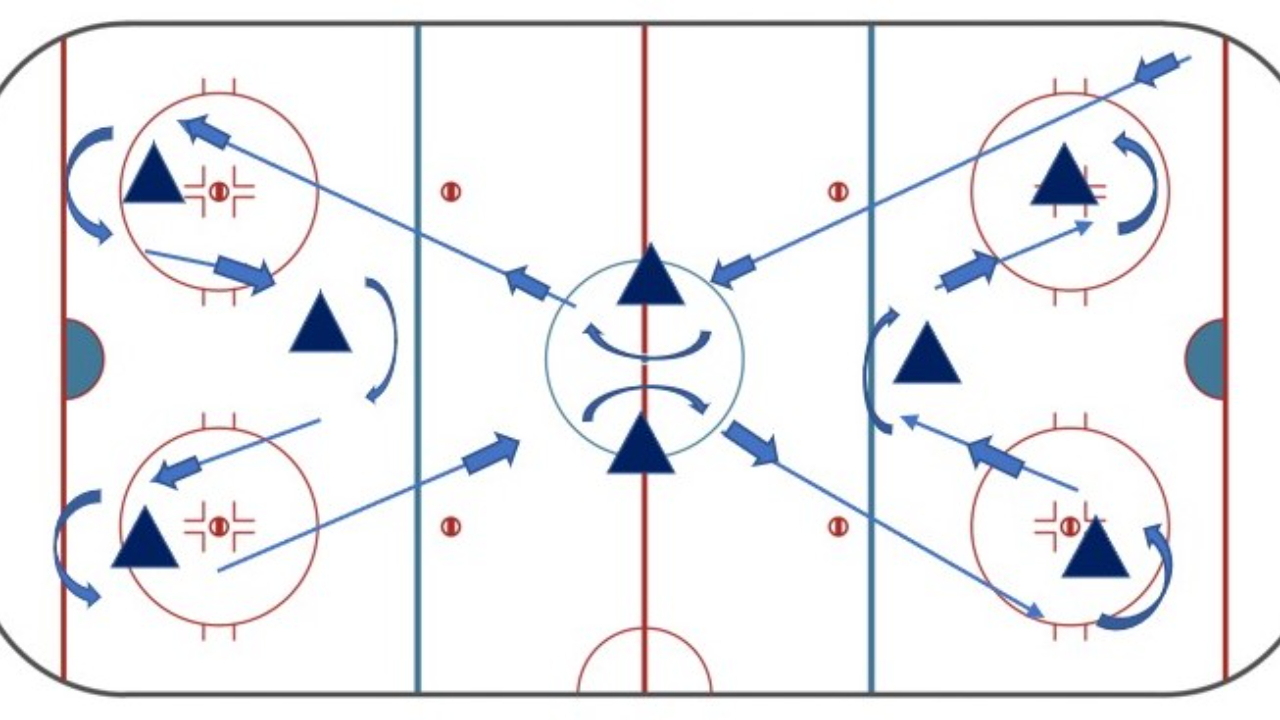

Considering a shift in hockey lasts 30 – 45 – 60 seconds, this means players are on the ice working hard for a relatively short period of time, then get fatigued and need to come off the ice to rest and recover. During the rest on the bench between shifts, the body does many things (to recover and get ready for more on-ice work):

- The players “catch their breath.”

- The body clears some of the waste products produced by high intensity work.

- The players mind “clears” and gets ready for the next shift.

In terms of training for hockey, as mentioned above, specificity of training is the key to success in anaerobic sports. Therefore, in order to be able to perform at a high intensity, the athlete needs to training anaerobically.

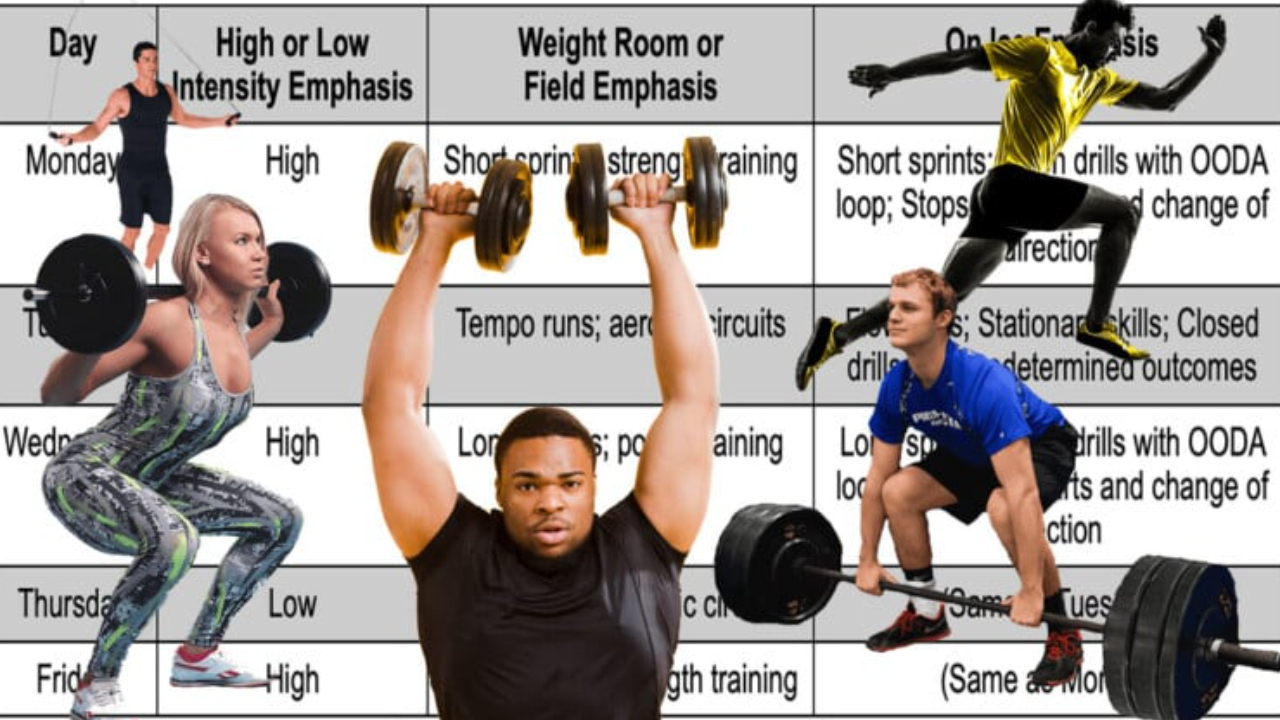

Interval training – this is training where the athlete works extremely hard (so that they are out of breath and there is a burning sensation in the muscles) for a short period of time, then rests for twice or three times as long as the work. A classic interval training program for hockey players could be the following:

- Running, riding a spin bike, or doing jump squats (just as examples) for 30-seconds, then resting for 1.5 – 2-minutes.

- The next interval would be running, riding a spin bike, or doing jump squats for 45-seconds, then resting for 1.5 – 2.5 minutes.

- The next interval would be running, riding a spin bike, or doing jump squats for 60-seconds with a 2 – 3 minute recovery.

- The fourth, fifth, and sixth intervals would be 60-seconds, 45-seconds, and 30-seconds with 1.5 – 2 minutes rest between intervals.

This is just an example of an interval training program. However, there are many different programs to enhance anaerobic capacity.

The beauty of interval training is that it trains the body for high intensity work and it trains the body to recovery quickly. This is not to suggest that hockey players should never do aerobic conditioning. Long slow distance training is best done right after the season has ended in the active rest phase of the off-season training program. And it could be done for approximately 1 – 1.5 months.

Muscle fiber type and training

Another reason for hockey players to be doing predominately anaerobic training is because it trains the fast twitch muscle fibers. As was mentioned above, there are two kinds of muscle fibers: 1) fast twitch fibers and 2) slow twitch fibers. Having said that, there are actually more than two fiber types, but to go deep into muscle physiology is beyond the scope of this article.

Fast twitch muscle fibers contract fast and powerfully. It is the fast twitch fibers that help a player skate fast, shoot quickly, react to plays on the ice quicker, and makes a player faster in all aspects of the game. Therefore, when a player trains to enhance the anaerobic system, it improves his or her ability to do high intensity work on the ice. Part of anaerobic training is also jump training and weight training, both of which are important for developing powerful muscles.

If a player does a lot of medium intensity continuous training, ie: “cardio,” it trains the slow twitch fibers, which is not specific to enhancing performance on the ice.

Conclusion

Anaerobic training is the essential type of training to enhance hockey performance. Anaerobic training, or more specifically, interval training, helps the body prepare for high intensity work on the ice, and recovery after the shift. Jump training and weight training are also important forms of anaerobic training as well.

This story is available exclusively to members of The Coaches Site.