🧠 Sticky Learning vs Rehearsal

Why Block Practice Doesn’t Translate to the Game

By Coach Barry Jones | IIHF Level 3 | USA Hockey Level 3

🎯 The Practice Paradox

Ever had a player light it up in practice, only to go missing on game day?

They hit every pass, every shot, every cue you drilled into them all week…

Then come game time, it’s like they’ve never seen the puck before.

That’s not just a player problem.

That’s a practice design problem.

It’s the difference between rehearsal and learning.

Between a skill that looks sharp in isolation…

And one that sticks when it counts.

🧩 Rehearsal: The Allure of Block Practice

Let’s start with block practice.

It looks clean. Linear. Measured.

Same rep. Same movement. Same result.

You run 10 slap shots from the same dot. Players improve visibly. Confidence climbs.

But that improvement? It’s often an illusion.

Block practice is like memorising lines in a play:

It works when the stage is set exactly the same way.

Change the context, and everything unravels.

Why Block Practice Feels Good:

- Immediate success.

- Short-term performance gains.

- Isolated technical refinement.

What’s Happening in the Brain:

- You’re working in the motor cortex and cerebellum, where motor planning and fine motor control live.

- The skill lands in working memory, easily recalled in the moment, but not retained under duress.

It’s not that block practice is bad; it’s just limited.

You’re teaching athletes a rehearsed solution to a fixed problem.

🔄 Sticky Learning: The Power of Random Practice

Now let’s flip it.

Random practice is messier.

It introduces variability, unpredictability, and pressure.

Instead of 10 identical shots, now players shoot off different passes, angles, defenders, speeds, maybe even off a rebound.

And yes, it looks worse at first.

But that mess? That’s where sticky learning happens.

Why Random Practice Matters:

- Deeper cognitive engagement.

- Enhanced problem-solving.

- Long-term retention.

- Real-game transfer.

Brain Science Behind It:

- Activates the prefrontal cortex (decision-making).

- Engages the hippocampus (retrieval of past experiences).

- Connects sensorimotor networks to perception in real-time.

This isn’t just doing a skill, it’s solving problems with that skill.

Players aren’t just acting; they’re perceiving and acting, simultaneously. That’s perception–action coupling, the invisible thread of real hockey IQ.

🧠 Brainwalk: A Walkthrough of the Same Drill, Two Ways

Let’s bring it to life.

Scenario: Shooting after receiving a pass from below the goal line.

Block Practice Version

- Coach feeds a pass from behind the net.

- Player receives it in the slot and shoots.

- 10 identical reps.

🧠 Brain Response:

- Engages motor cortex + cerebellum.

- Skill “feels good,” but is anchored to that exact scenario.

- Poor adaptability when timing or angle changes.

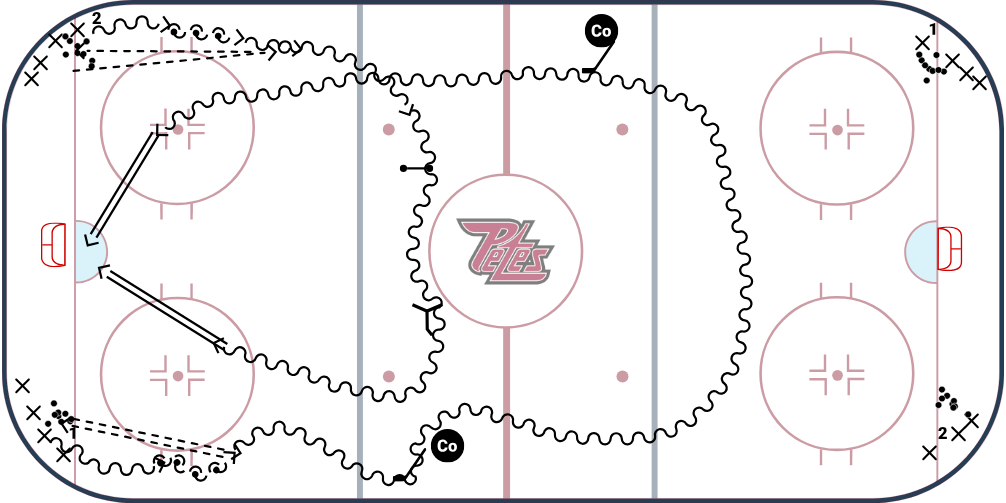

Random Practice Version

- Pass comes in late, early, from different sticks.

- Defender may close, Goalie positioning changes.

- Player must shoot, deke, delay, or pass, depending on what they see.

🧠 Brain Response:

- Engages hippocampus (past pattern recall),

- Prefrontal cortex (on-the-fly decisions),

- Visual cortex (tracking movement),

- Sensorimotor coupling (reading & reacting).

Outcome? The rep is less “perfect,” but the learning is real.

⚖️ The Challenge Paradox: Where Learning Lives

Not all reps are created equal.

If practice feels too easy, chances are… the athlete isn’t learning.

If it feels too hard, they’re overwhelmed.

But right in the middle? That’s where growth lives.

This is the Challenge Paradox.

Let’s break it down:

Block Practice and the Illusion of Mastery

In a typical block drill:

- Reps are consistent.

- Movements are prescribed.

- Outcomes are nearly guaranteed.

The result? A 100% success rate, but a 0% problem-solving rate.

The only real challenge is remembering what the coach said to do.

Game Environments and Real Constraints

At the other extreme:

- The game is unpredictable.

- Opponents adapt.

- Space, time, and decisions collapse under pressure.

Even the best athletes might win only 50% of their reps.

The rest? They’re testing the edges of their attractors, failing, adapting, and learning.

The 70/30 Ratio: The Sweet Spot for Sticky Learning

Here’s where the science gets exciting.

Research in motor learning and ecological dynamics shows that the ideal challenge ratio for learning is about 70% success to 30% failure.

At this ratio:

- Athletes are stretched but not broken.

- They succeed often enough to stay confident…

- But fail just enough to stay adaptive.

This is the zone where:

- New attractors emerge.

- Perception–action loops tighten.

- Sticky movement solutions are formed.

Too much success? They plateau.

Too much failure? They disengage.

Find that middle zone, and the brain lights up with possibility.

🌐 What Block Practice Misses: Constraints, Attractors, and Affordances

In ecological dynamics, athletes learn through interaction, not isolation. When we remove variability, we strip out the elements that make the learning stick.

Here are three key ingredients that block practice often ignores:

- Constraints – These are boundaries or conditions that shape behaviour. They come from:

- The task (e.g., type of pass, speed of play)

- The environment (e.g., space, time, pressure)

- The athlete (e.g., fatigue, physical capacity, emotional state)

- Rate Limiters – Internal or external factors that temporarily cap performance. Think: vision under fatigue, edge control in traffic, or scanning under pressure.

- Affordances – The opportunities to act an athlete perceives in their environment. A passing lane isn’t just space, it’s an invitation. But it only exists if the athlete sees it.

- Attractors – Stable, preferred movement patterns that emerge under certain conditions. Think of a natural pivot on a loose puck or a go-to shooting stance. These develop through repetition in context, and can be adapted or destabilised through varied reps.

Start With the Game

Too often, coaches begin with clean, isolated technique and only later add complexity. But what if we flipped that?

Start with small area games; the game reveals the problem.

If an athlete struggles to solve that problem, then and only then use block practice as a temporary tool to refine a movement or expose a missing experience.

But here’s the key: scale is everything.

Don’t throw them into chaos with five defenders and six cues to process.

Instead:

- Start with just enough information for the athlete to perceive, act, and problem-solve.

- Adjust the complexity of the task environment to match the challenge ratio.

- Scale up as the athlete succeeds or scale down if they hit a wall.

- Only when the game design fails to support learning should you shift temporarily into reductionist block practice, and only to reframe or reveal a new attractor.

In this model:

- The game is the teacher.

- The rep is the response.

- The coach is the designer.

- Scale is your lever.

🔧 Building a Sticky Practice Plan

Here’s how to design learning that sticks:

1. Begin with Chaos (SAGs and Game-Like Reps)

- Use small area games to reveal decisions, gaps, and strengths.

- Let the environment coach.

- Identify if the athlete can problem-solve under pressure.

2. Observe, Don’t Prescribe

- Watch for affordances perceived and acted upon.

- Identify rate limiters, physical, cognitive, or emotional.

- Notice attractor patterns that emerge (helpful or not).

3. Use Block Practice Strategically

- Only after the athlete shows a clear breakdown.

- Focus on one motor solution at a time.

- Reinforce feel and mechanics, then reintroduce into chaos.

4. Return to Variability

- Bring the refined skill back into game-based situations.

- Let the athlete test it under pressure and adjust it.

- Allow attractors to re-stabilise in functional contexts.

5. Prioritize Feedback That Sticks

- Use guided questions (“What did you see?”)

- Encourage reflection, not just correction.

- Reinforce decisions, not just outcomes.

🧬 Where to Start: From Rehearsal to Reality

Here’s the takeaway:

You don’t need to abandon block practice.

Just don’t start with it.

Start with:

- The chaos of game-like situations.

- Use block if necessary, as a tool to explore and refine.

Then return to variability.

That’s where sticky learning lives.

Because real skill doesn’t live in your drill design,

It lives in the decisions your athletes make when the game breaks down.

🏒 Final Thought: The Game Isn’t Scripted, Why Should Practice Be?

The game doesn’t hand you the same cue twice.

It doesn’t give you time to rehearse.

So, let’s stop preparing our athletes like it does.

Let’s move from repetition to representation.

From drills to decisions,

From rehearsal to sticky learning.

Because when the puck drops,

It’s not the clean rep that shows up, it’s the sticky one.